Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

Labor Day is a New York City-born and bred holiday first celebrated this week on September 5, 1882. Of all the national holidays, Labor Day seems to be the one that most people know almost nothing about. But, after this read you’ll be able to tell all your friends why we have the first Monday of every September off.

The holiday has its roots in a common 19th-century tradition where laborers would have picnics and parades to draw awareness to worker’s rights. From these gatherings came the genesis of organized unions. New York, already a hotbed of the American Industrial Revolution by the 1880s, saw various unions spring up in an attempt to protect workers from typical capitalist abuses such as low wages and unfair hours.

In January of 1882 the Knights of Labor and the Tailor’s Union held a rally at Cooper Union which led to the creation of a city-wide trade consortium. They called the group the Central Labor Union of New York, Brooklyn, and Jersey City or (CLU). In an attempt to rally more workers to their cause they proposed that a day each year be celebrated to honor the working masses with parades and celebrations. To show the country just what they meant they organized a “Labor Day” parade on Tuesday, September 5 of the same year.

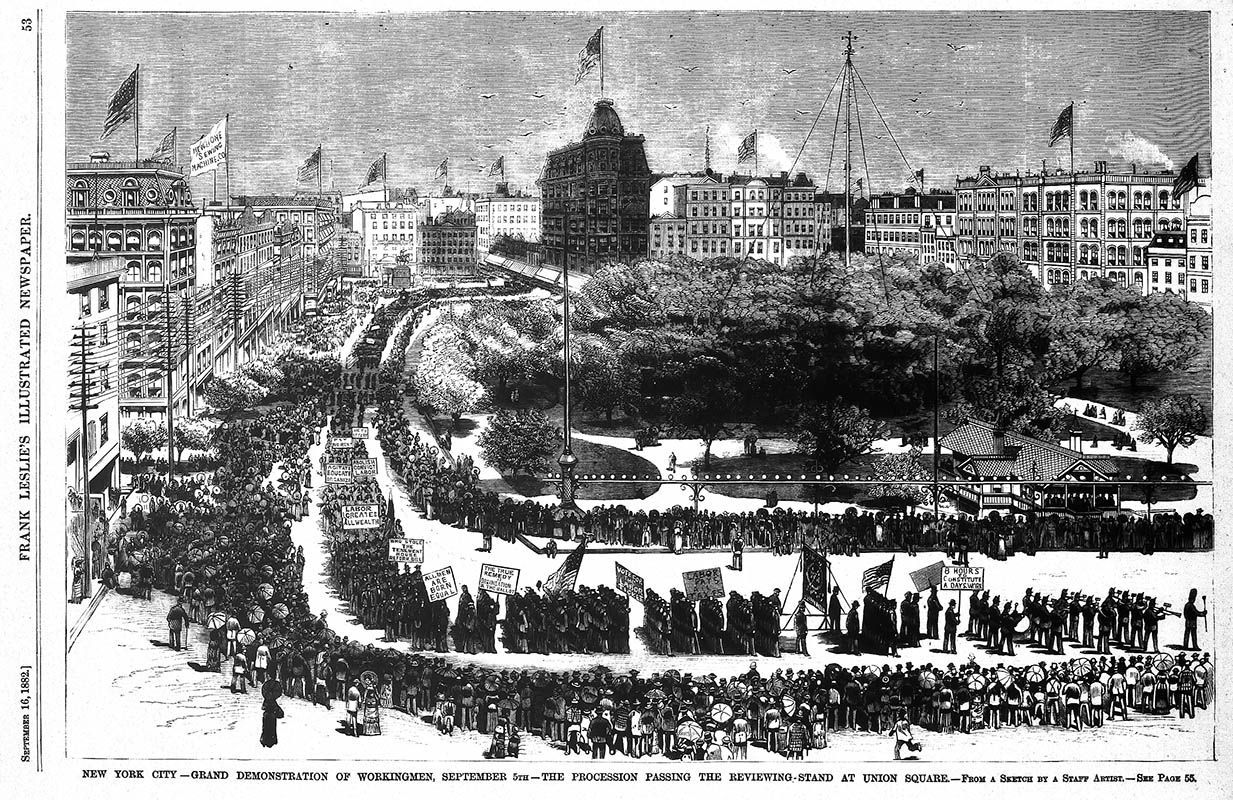

Unions showed up outside City Hall in distinctive garb bearing colorful banners and signs. According to the book Gotham, The Jewelers Union of Newark led the parade with their own band donned in dark suits and derby hats. The bricklayers were behind them in white aprons followed by 700 members of the typographical union, also known as “The Big Six.” They carried banners that read: NO MONEY MONOPOLY and LABOR BUILT THIS REPUBLIC AND LABOR SHALL RULE IT. It was said that the marchers were in high spirits and sober as no drinking was allowed during the parade.

The New York Times reported:

The parade of the working men yesterday, although not so large as its organizers had predicted, was conducted in an orderly and pleasant manner. Those who rode or marched in the procession were cheerful, and evidently highly gratified with the display. Nearly all were well-clothed, and some wore attire of fashionable cut. The great majority smoked cigars, and all seemed bent upon having a good time at the picnic grounds. The originators of the labor demonstration, as the parade was spoken of, frankly admitted that the working men were determined to show their numerical strength in order to satisfy the politicians of this City that they must not be trifled with.

The parade was said to be 20,000 men strong as it marched past Canal Street to Union Square. Hundreds of seamstresses hung out the windows along the route cheering the procession blowing kisses and waving their handkerchiefs.

The book Gotham described how the parade wrapped up its festivities:

Finally, after passing by a reviewing stand filled with labor dignitaries, the participants adjourned, via the elevated, to an uptown picnic at Elm Park. There they danced to jigs by Irish fiddlers and pipers and were serenaded by the Bavarian Mountain Singers while the flags of Ireland, Germany, France, and the USA flapped in the autumn air.

By 1884, Labor Day showed up as a municipal holiday in certain towns around the country. In 1887 it was starting to be recognized by individual state governments with New York, New Jersey, Colorado, and Oregon being the first handful of states to legalize Labor Day. Finally, in 1894, the 53rd Congress moved that the first Monday of every September be set aside as a day to recognize the working men of this country.

Humorous aside: There has been a long debate over the gentleman who actually proposed the idea of Labor Day. Some records show that Peter J. McGuire, secretary to the Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners and cofounder of the American Federation of Labor was on record suggesting that a day be set aside to celebrate those “who from rude nature have delved and carved all the grandeur we behold. Yet there are those who believe a man by the name of Matthew Maguire, the secretary of Local 344 of the International Association of Machinists of Paterson, NJ had the idea for the holiday when he was secretary of the Central Labor Union in 1882. Others contest that the confusion lies in the similar phonetics of their names. Regardless, we Americans now have the first Monday of September off from our labors to BBQ, go to the beach, or binge-watch the latest shows (like “Only Murders in the Building” or the last season of Billions, thanks to a group of picnic-loving 19th Century New Yorkers. Hazaaah!

Next, check out more from our column Today in NYC History.

Subscribe to our newsletter