Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

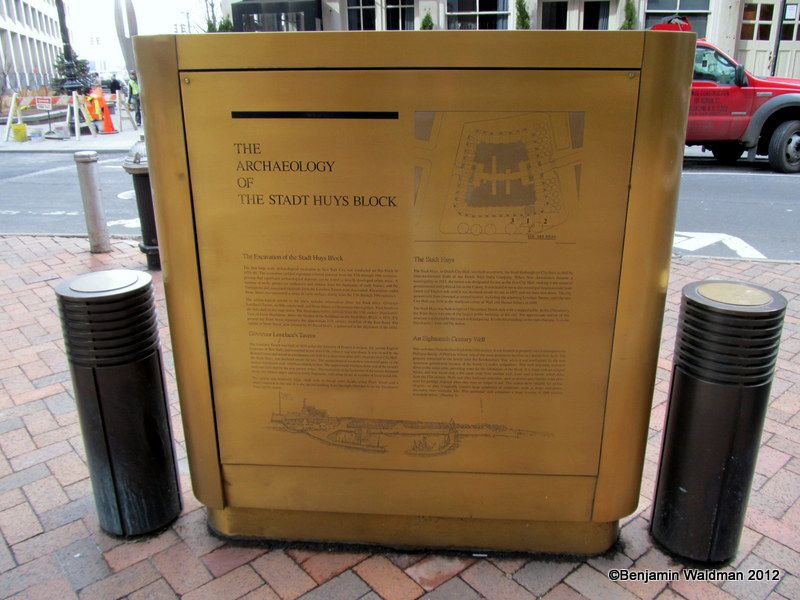

Last we spoke about Dutch New Amsterdam, we unraveled the story behind Governor Lovelace’s tavern, a 17th century bar whose remnants are located in what is now the Financial District in lower Manhattan. Cordoned off by brass railings, the building’s original grey foundation can be seen through a glass window in the sidewalk at 85 Broad Street. Nearby, you’ll also notice a yellow rectangle of bricks that outlines the walls of Stadt Huys, Manhattan’s very first City Hall. A soaring high rise now stands at 71 and 73 Pearl Streets, where the municipal building originally stood, but its history is not entirely lost to time. Today, we’ll delve into its backstory, which you can learn more about on our upcoming Tour of The Remnants of Dutch New Amsterdam.

Tour of The Remnants of Dutch New Amsterdam

New York City’s present City Hall was constructed between 1803-1812, while its predecessor was completed in 1700. Prior to that came Stadt Huys, originally built in 1641 as a tavern (City Tavern) and the town’s first hotel at the request of Colonial Governor William Kieft, who had grown tired of entertaining guests at home. “Stadt Herbert,” as the building was initially called, served as a meeting place for politicians, town officials and activists. It was later commissioned as the first City Hall in 1653—the same year the Dutch settlement was deemed a city under a municipal charter.

In recognition of the building’s newly earned status, officials proclaimed that:

“… they shall hold their regular meetings in the house hitherto called the City Tavern, henceforth the City Hall, on Monday mornings from 9 o’clock, to hear there all questions of difference between litigants and decide them the best they can.”

In order to fully understand the appearance of Stadt Huys, author Alice Morse Earle in Historic New York writes that we need to first examine the town surrounding it during the 17th century. The shoreline back then was entirely different in appearance: Water, Front and South streets were part of the bay, which allowed water to roll up close to the base of Stadt Huys. The building stood alone “on the strand” for years, where it could seen by all incoming ships from the anchorage at Whitehall Street.

Morse Earle called Stadt Huys the “most important and historic building of the New Netherland days,” and its outward appearance certainly supported that claim. After all, its walls rose three stories tall and a rooftop tower added two more stories to its overall height, allowing it to stand virtually as a skyscraper during the mid-17th century. Not only did it serve as a meeting place, it was the site for various ceremonies, tributes and trials. The 50-foot-square stone structure also bore a cupola, which housed a bell that would ring at 9:00 am on court days.

A record of a trial, shared by Daytonian In Manhattan, provides us with a detailed description of the courtroom:

“Over the bench of the Justices are interweaved the orange and blue and white colors of the West India Company, with the tricolor of Faderland. Around the room hang the leather fire-buckets ready for use. On the magisterial seat are placed the stuffed red cushions, which are carried to the church on Sundays, and which are to hold the weight and judicial wisdom of New Amsterdam. Behind is the painted coat of arms of the City, sent over by the Directors from Holland in 1634…Against the wall is the nut-wood chest, where are kept under massive clasps and bands the records and archives of the court.”

Unfortunately, due to Stadt Huys’ proximity to the shore, water consistently lapped at the building’s foundation causing it to fall into despair by 1697. Fearing that the structure would collapse in, officials refused to conduct meetings inside. Stadt Huys, as a result, was sold on August 23, 1699 to a merchant named John Rodman for £920; the building was eventually torn down and the Lovelace Tavern next door came to serve as a substitute meeting space until the second City Hall was constructed in 1700, which—for the sake of comparison—cost £4000 to construct.

Remnants of the Lovelace tavern on 85 Broad Street

Today, Stadt Huy’s legacy is remembered by keen, eagle-eyed New Yorkers who take notice of the yellow bricks planted below their feet. You can learn more about its story by exploring Dutch New Amsterdam with us on an upcoming tour.

Tour of The Remnants of Dutch New Amsterdam

Next, check out The Remains of the 17th Century Lovelace Tavern in NYC’s Financial District and 10 Things the Dutch Introduced to NYC and America from Bowling to Santa Claus to Democracy.

Subscribe to our newsletter