Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

Does newspaper have a sound? Is it the rustling of paper? The pop-up ads of the digital world? The short films on the New York Times website? Or might it also be articles and editorials read aloud to old-country parents or to grandmothers and grandfathers that can’t read?

At the turn of the twentieth century, Yiddish newspapers were material documents of life on the Lower East Side. They were guidebooks to old-world communities and to new-world assimilation. They taught immigrants how to be American, but they did so in foreign languages. They tied people together, tied people who didn’t know one another together in the common experience of reading about the day’s affairs. You didn’t have to be face-to-face with your neighbors to feel connected to them.

But as much as they were read, these newspapers were also spoken compositions. They were public events where Jews would gather together and collectively receive words they weren’t literate enough to read.

Little is known about spoken newspapers, largely because of the fact that their very spoken-ness makes them so hard to document. The phenomenon is often connected to Yiddish language papers like the Forverts, now the Jewish Daily Forward. This was a Jewish-American, socialist paper from turn of the century New York, founded in 1897 and edited by Abraham Cahan from 1903 to 1946. Promoting socialism as an alternative to American capitalism, the paper captured the attention of immigrants living in the slums of the Lower East Side and working in the sweatshops of Gotham.

Marked by both its socialism and its dialect, the Forverts was published for this recent immigrant audience in their native tongue of Yiddish. Yiddish was a vernacular language among Eastern European Jews, spoken primarily in the home, as opposed to more formal, intellectual, public languages like Russian and German. Thus it seems natural that the colloquialism of Yiddish newspapers which spoke to the everyday ways in which Jews would communicate with one another, would be extended via the verbalism of the spoken newspaper.

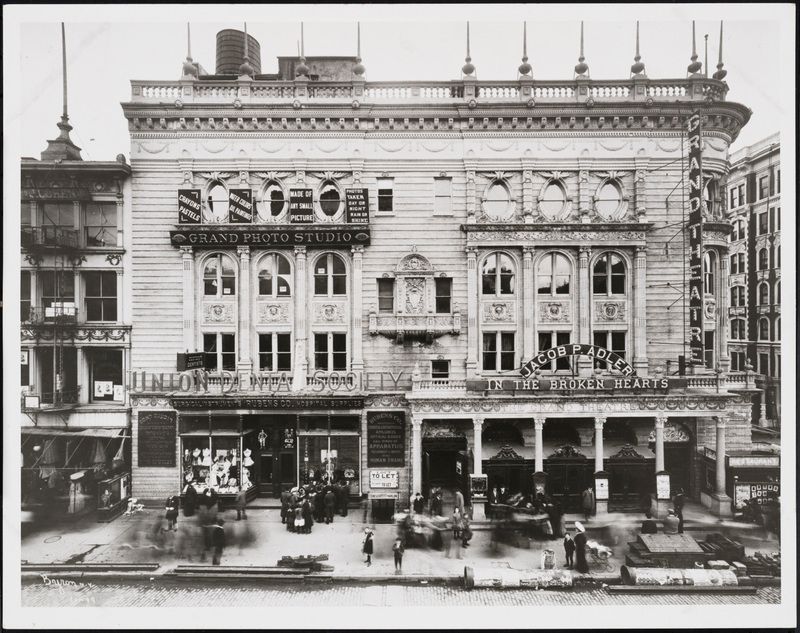

The Grand Street Theatre, once at the corner of Canal and Bowery. Photo from the Museum of the City of New York, from the current exhibition Yiddish Theatre: From Bowery to Broadway.

But where did they go to hear this news? Did they gather in the Lower East Side’s Yiddish Theater District, at sites like the Grand which opened in 1903, or the Loew’s Canal which still stands but has been abandoned since the 1950s? Or did they listen on street corners, in parks or plazas or squares? Knowledge of this sonic geography has not been preserved, but walking through these spaces (or perhaps watching The Knick) we can begin to imagine them a hundred years ago filled with immigrants seeking knowledge about their new strange home through the familiarity of their own language.

We can imagine Yiddish speaking Jews gathering at venues like the Loew’s Canal movie theater to hear the day’s news read aloud.

However, what we find in these spaces now is not immigration, but gentrification. Turn of the century tenements have been torn down and superseded by million dollar condos. The public sphere of the Forverts and the specificity of the vernacular newspaper spoken aloud has been replaced by the official English of the New York Times, and by institutions like Starbucks and tap rooms called The Immigrant. Where once people gathered together and came to consensus about politics and society, we now have mediocre, five-dollar lattes and eight-dollar microbrews. We can buy the New York Times at the Starbucks and imagine ourselves as New Yorkers and as Americans, but a paper like this doesn’t provide a space in which to talk back, a space in which to speak as much as to listen.

Starbucks, Tap Rooms, and Signs of Gentrification on the Lower East Side

Though there are few traces of these spoken newspapers in formal archives, YouTube videos of Yiddish film and radio dramas from the 1930s and 1940s offer a glimpse into what the spoken language sounded like. With its German foundations, its Slavic vocabulary, and Hebrew characters, Yiddish is a mish-mash of national and ethnic influences that sounds foreign even as its idioms—a schmear of cream cheese, a schlemiel, and a schlimazel—have become so familiar. It is this that we must imagine when we think of the spoken newspapers and how they reflect they spaces in which they were heard.

The Grand Street Theatre, the first construction of one specifically for Yiddish productions, 1905. Image from Museum of the City of New York

Yet as much as we imagine the art of how they sounded, we must also imagine what they said. Spoken newspapers were a form of communication for non-literate Jews trying to make it in America. However, Forverts did not offer capitalism and the American dream as the way to success, but instead proposed class consciousness and socialism—a social revolution of the proletariat to seize the means of production from their bourgeois overlords—as the way to make an impact in the new homeland of these new immigrants. By using Yiddish, by speaking Yiddish, these newspapers sought to reach these communities on their own terms rather than in the language of their oppressors. What they heard matched how they heard it and the place in which they heard it.

Next, read about the history of Yiddish Theatre in New York City, from Bowery to Broadway.

Subscribe to our newsletter