Fiber Arts Take Over a Former Seaport Warehouse in NYC

See waterfalls of fabric, intricate threadwork, massive tapestries, and more!

For years, boosters of Manhattan’s Little Italy have grappled with the realities of a shrinking footprint. Italian-Americans and their businesses have slowly been priced out of a neighborhood that has become more and more Chinatown West or Soho East, a shadow of its former immigrant robustness. They needn’t look farther than a couple miles to the south for a cautionary tale: an ethnic neighborhood that has been wiped almost clean off the map, a roughly 6-block stretch of Washington Street once known as Little Syria.

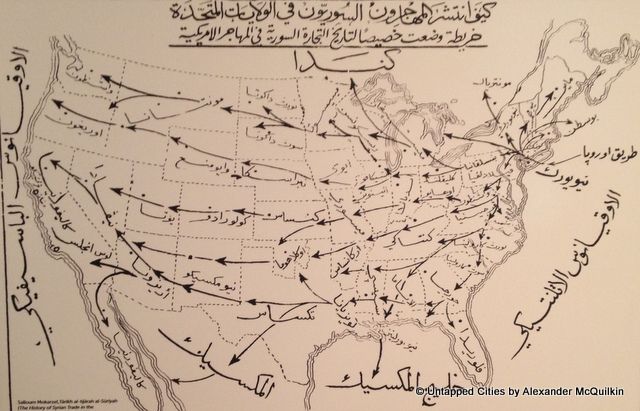

“Little Syria” is a bit of a misnomer, since the immigrants who settled there between 1880 and 1940 represented at least 27 different nationalities. Their exact origins are difficult to pin down given the political turmoil and constantly shifting boundaries in Europe and the Middle East around the turn of the century. But what many of them had in common was their Arabic tongue; Little Syria was the first Arabic-speaking immigrant base in the United States, preceding what would become a broad fanning out to other regions, the largest concentration today in suburban Detroit.

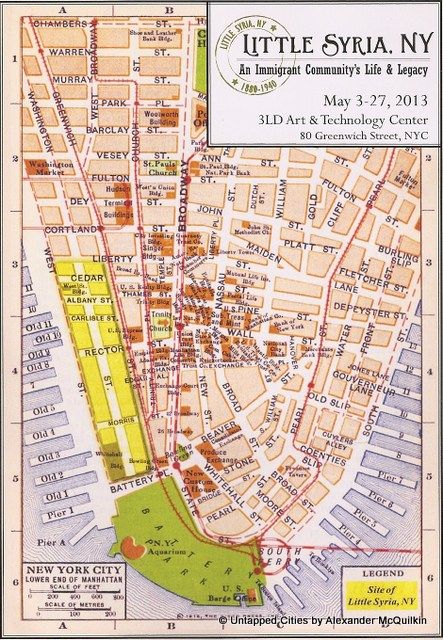

They settled in lower Manhattan for the same reason lots of immigrant groups did – proximity to the docks. The port was New York City’s lifeblood and required intensive human labor. While the men worked the docks, Little Syria’s women, schooled in silk craft in their home countries, discovered America’s blooming obsession with lingerie, and opened dozens of silk underwear shops along Washington and Greenwich streets. The residential neighborhoods abutting the waterfront were the dirtiest and most dangerous in the city, but they were also the cheapest.

According to Joe Svehlak, one of Little Syria’s historical torchbearers, the construction of the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel in 1946 signaled the “first death knell” for the neighborhood. (The development of the World Trade Center in the 1970s would be the second.) Designed by New York City’s almighty mid-century master planner Robert Moses, the Manhattan approach to the tunnel was to occupy an extraordinarily sprawling swath of land that was marked by rows of tenement buildings and warehouses. Eminent domain gave residents just days to relocate and, lacking the agency of the modern preservation movement, they obliged.

But by then, Little Syrians had already begun to leave the neighborhood, many settling along Atlantic Avenue in Brooklyn, a quick ferry trip away from their “mother colony” in Manhattan. Today, Atlantic Avenue has proven much more resilient than Little Syria – it remains a hub of Middle Eastern food and culture.

Meanwhile, back in Manhattan, Mr. Svehlak and a coalition of preservationists called “Save Washington Street,” have been lobbying the city’s Landmarks Preservation Commission to protect what they say are the last surviving traces of a defunct neighborhood: a contiguous row of three 19th-century buildings including a tenement, a community center, and a church. The last of these, St. George Syrian Melkite Catholic Church, was successfully landmarked in 2009. A former tenement that was converted to a church by a Syrian-American architect in 1929, the building was home to an Irish pub for 25 years until noise from construction of a tower next door forced it to close its doors in 2011. That tower, a 50-story Holiday Inn still under construction, and the recently completed W Downtown hotel up the street, dwarf the fragile trio.

But Mr. Svehlak, who led a tour of the neighborhood on behalf of the Municipal Art Society last weekend, is optimistic on at least one front. He says the 62-year-old George’s, an unassuming restaurant on the corner of Greenwich and Rector streets, offers an enduringly authentic taste of the neighborhood’s Mediterranean past.

The Arab American National Museum is hosting a pop-up exhibit on Little Syria at the 3LD Art & Technology Center (80 Greenwich St.) through May 27. Friends of the Lower West Side will be conducting a walking tour of the neighborhood from the same site on May 21 and 23 at 1 pm (suggested $10 donation).

Subscribe to our newsletter