Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

What does the word Freemasons conjure in your mind? Practitioners of occult rituals? Old white presidents? Or perhaps, a polite term for the Illuminati? Tom Savini, director of the Chancellor Robert R Livingston Masonic Library and our guide for the hour and a half long tour organized by Atlas Obscura, has heard it all before. With a rather weary chuckle, he tells me that the Masons have been accused of everything from baby kidnappings to human sacrifices. I ask him if the Livingston Masonic Library contains any such sensationalist material or if it archives manuscripts that more accurately represent the Faith, if it can even be referred to as such. Savini is emphatic when he says, “No, we still contain these materials, if only to give visitors a comprehensive view of the Freemasons. We don’t try to tell anyone how to think here.” His response itself speaks volumes about what may just be the true tenets of Freemasonry.

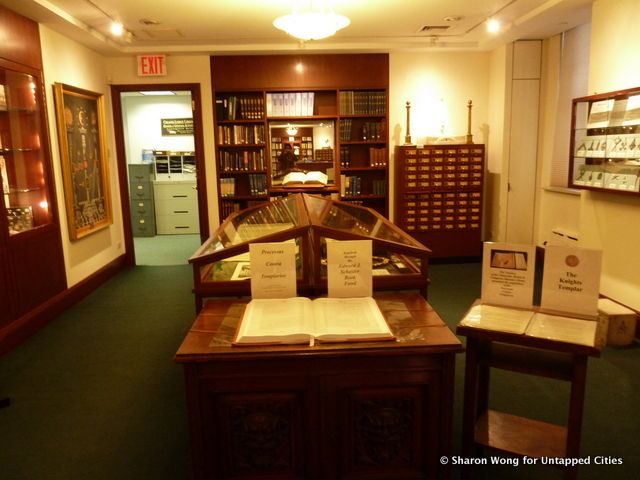

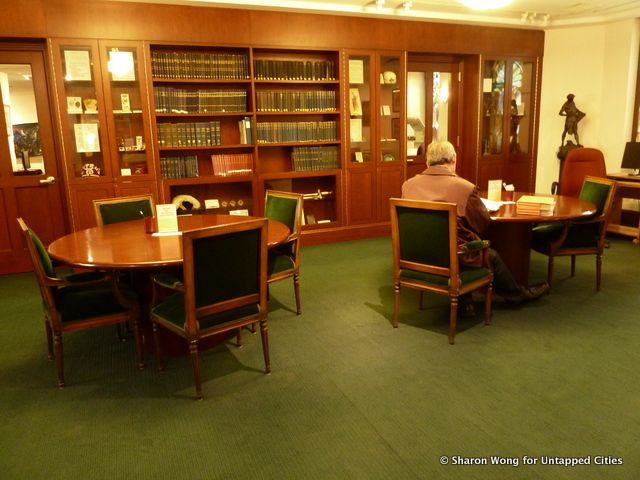

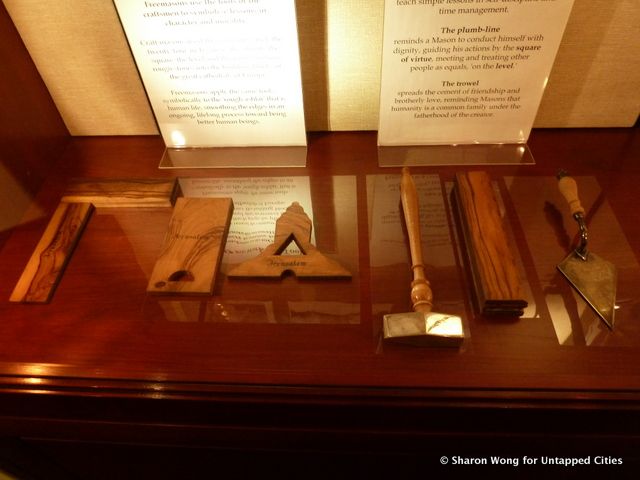

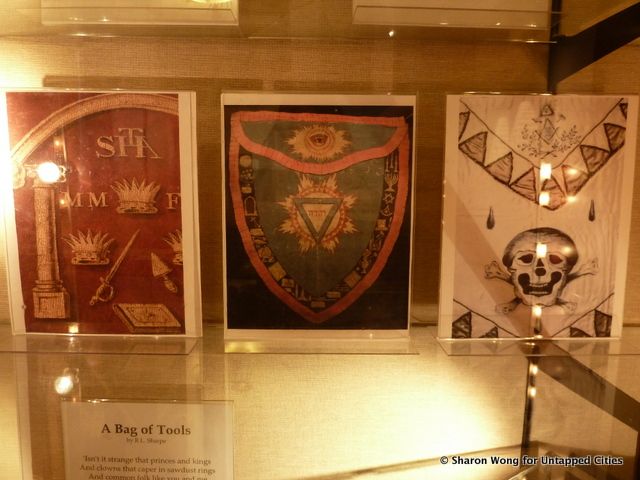

The Livingston Masonic Library is a classically beautiful space located on the 14th floor of Masonic Hall on West 23rd St. It is as much a repository for relics as for books, containing cases full of beautiful objects, each wielding their own special significance. Some of the most iconic are the building tools, symbols of the group’s possible beginnings among the guilds of stonemasons during the Middle Ages.

The gavel and gauge represent self-discipline and time management while the plumb line reminds a Freemason to carry himself with dignity. The trowel, in turn, stands for the qualities of friendship and brotherly love, which Savini tells us are two integral foundations upon which Freemasonry is based. Who would’ve guessed?

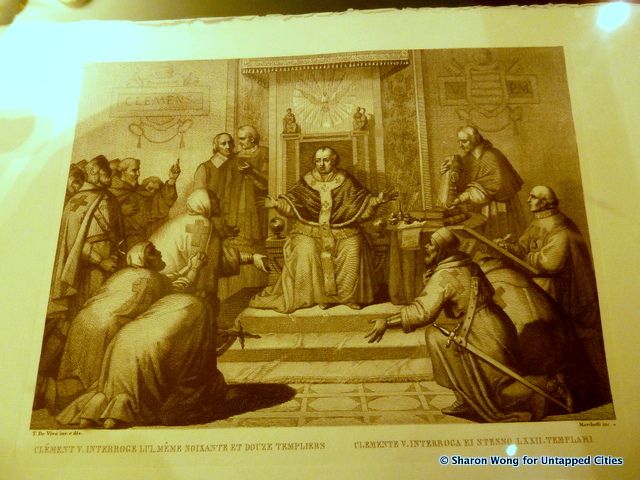

Another popular theory regarding the beginnings of Freemasonry has to do with the Knights Templar, the group of Christian warriors erected to protect pilgrims traveling from Jaffa into Jerusalem. This philanthropic group was eventually severely persecuted by King Phillip IV of France and disbanded in 1312. However, some of their practices were said to have been preserved by the Masons, who were greatly inspired by their story. The Livingston Masonic Library displays a facsimile of the Processus Contra Templarios, a depiction of trials against Templars in 1308.

Then, there are the weave aprons, badges and pins denoting office

Duties are ascribed when a member becomes a 3rd degree Mason. The Master of the Lodge is decided by vote and usually keeps his office for one year. According to Savini, members are absolutely not allowed to talk to one another about who they have voted for. Secrecy within an already tight-lipped group? The plot thickens.

Also of note is the tracing board, an essential audiovisual aid during Masonic degree rituals, performances with long scripts.

As a rule, Freemasonry’s insider knowledge is passed on orally so that outsiders will never accidentally get hold of their secrets. As a result, extensive memorization becomes an integral part of even the lowliest Freemason’s life. I was impressed. I am such a bad memorizer that I’m sure not even the pictures would help, beautiful as they are.

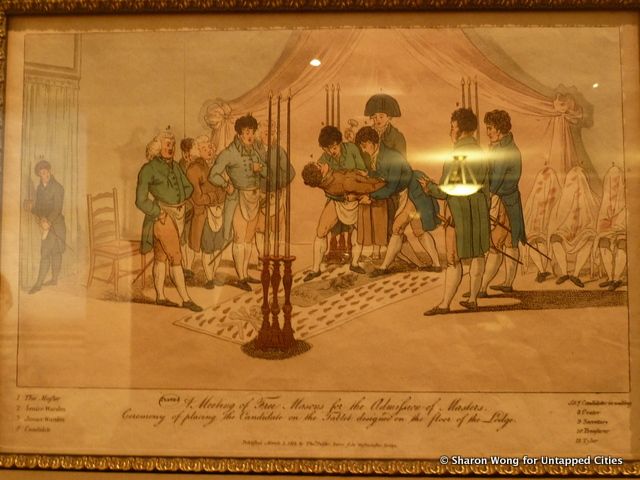

Savini then draws our attention to artifacts that seem a little more unique to the Livingston Masonic Library. The first of these were seven illustrations dated 1810 and 1812, all depicting possible scenes from Masonic rituals.

When someone in the group asks Savini which are the most accurate, he smiles and playfully retorts, “We like to let our visitors draw their own conclusions here.” For some reason, I was drawn to this particularly sinister-looking image

I wasn’t sure if I would be happier if it were the artist’s flight of fancy or if it were reality being stranger than fiction.

The Livingston Masonic Library also showcases several decorative china pitchers from the late 1700s, all presumably used during Masonic banquets.

Savini told us that Freemasonry evolved from a desire among the bourgeoisie to form a group of enlightened, civilized individuals, so taking genteel repast after gatherings was certainly not unheard of. Another special artifact at the Livingston Masonic Library is the desk of Norman Peale, author of The Power of Positive Thinking.

This prominent Mason was also the founder of the self-help movement, an achievement Savini doesn’t seem to regard as one of Freemasonry’s prouder moments. To add a hint of historic gravitas, there is also the grandfather clock that stood in the lodge in Yorktown, Virginia during the Masonic banquet celebrating Cornwallis’ surrender in 1781!

As for the books, the Livingston Masonic Library holds a full spectrum of views on Freemasonry, both from within and without the group. One of the more sensational accounts is Occult America by Mitch Horowitz, who offers an outsider’s perspective on Freemasonry. For a more balanced view, you can also check out Washington: A Life by Ron Chernow, a biographer of America’s first president and one of the most eminent Freemasons in history.

After the tour, I ask Savini why he thinks Freemasonry receives so much bad publicity. “Well,” he says, “Because of its secrecy, Freemasonry is often associated with revolutionaries. I mean, after all, many Freemasons were behind the French revolution, bloodiness and all. Also, we do count many of history’s most famous rebels among us. Simon Bolívar is an example”.

After all this, I wanted to know, what do Masons actually believe? Savini replies, “Without saying too much about our inner workings, I’d say that our primary belief is tolerance. We have members of all faiths and political leanings, but we never discuss these within the Lodge. We prefer our focus to be equality and the friendship between like-minded men.” If you ask me, it sounds a lot like what we teach our children, arcane rituals notwithstanding.

Located on 71 West 23rd St on the 14th floor, the Livingston Masonic Library is open to the public on MWF 8:30am-4:30pm and Tuesday 12:00pm-8:00pm. If you want to take a tour, call at (212) 337-6620 or email at info@nymasoniclibrary.org.

Subscribe to our newsletter