How to See the Liberty Bell...in Queens

A copy of the famous American bell can be found inside a bank, which itself is modeled after Independence Hall!

Newtown Creek, which separates Brooklyn and Queens and flows into the East River, is today both a Superfund site and a hotspot of new residential development. Its industrial history is well-documented, but what is forgotten is that in 1881 New York’s governor and a leading national magazine battled aggressively, though unsuccessfully, to stop the damage to public health and the environment caused by refineries and factories located along the creek. Turns out, it didn’t become an environmental nightmare without a fight.

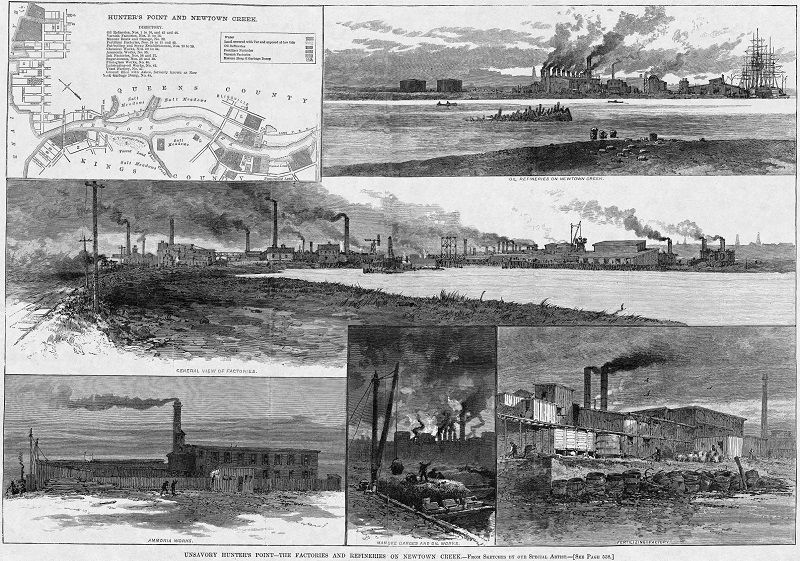

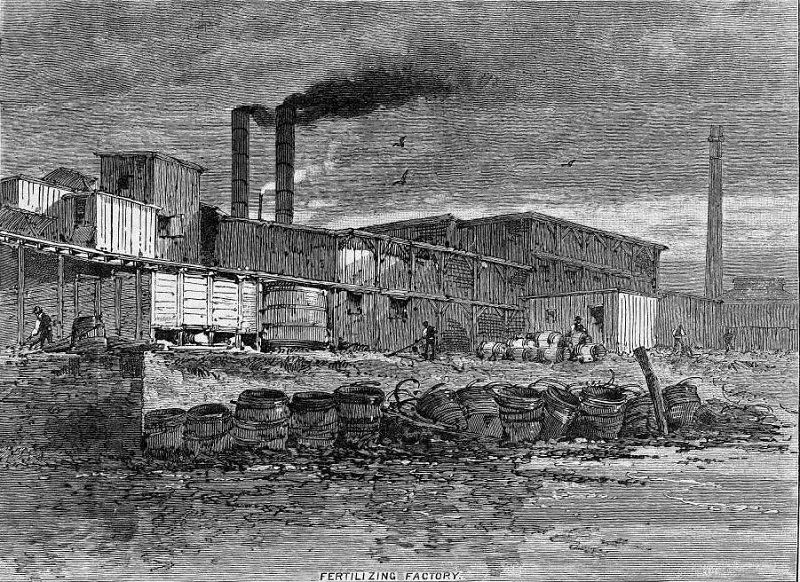

Once an ecologically rich waterway, around the time of the Civil War heavy industrial uses sprang up along Newtown Creek. The neighborhood along the north bank of the creek, Hunter’s Point, became synonymous with oil as several refineries were established there. By 1881, the area was also known for its foul stench and the release of sludge acid and other wastes into the waterway by the refineries and other businesses.

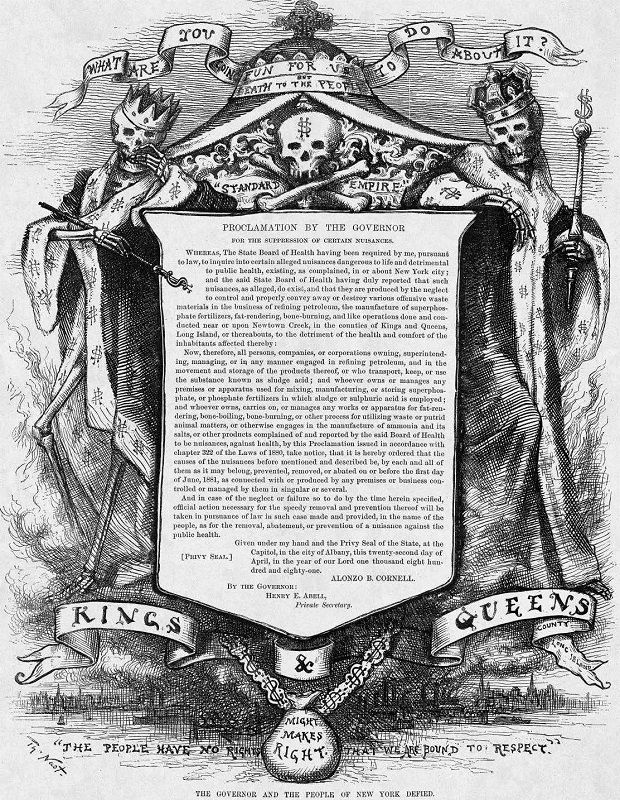

Harper’s Weekly, 13 August 1881, by Thomas Nast

In April 1881 Gov. Alonzo B. Cornell issued a proclamation requiring that “nuisances dangerous to life and detrimental to public health” in and around Newtown Creek be “prevented, removed, or abated.” This followed earlier legal actions against “Newtown Creek Nuisances” that had been ineffective in ending “sickening stenches.” Compliance with Gov. Cornell’s proclamation was required by June 1, 1881.

Harper’s Weekly, 6 August 1881

The proclamation’s June deadline passed and, as the New York Tribune observed, the Newtown Creek industries “stoutly disregarded it.” Harper’s Weekly, a leading national magazine, then picked up the cause in August and ran a series of articles and editorials harshly attacking the Newtown Creek companies, including Standard Oil. The magazine and its political cartoonists, including Thomas Nast, portrayed the businesses as arrogant merchants of death who enjoyed “fun for us” but brought “death to the people.”

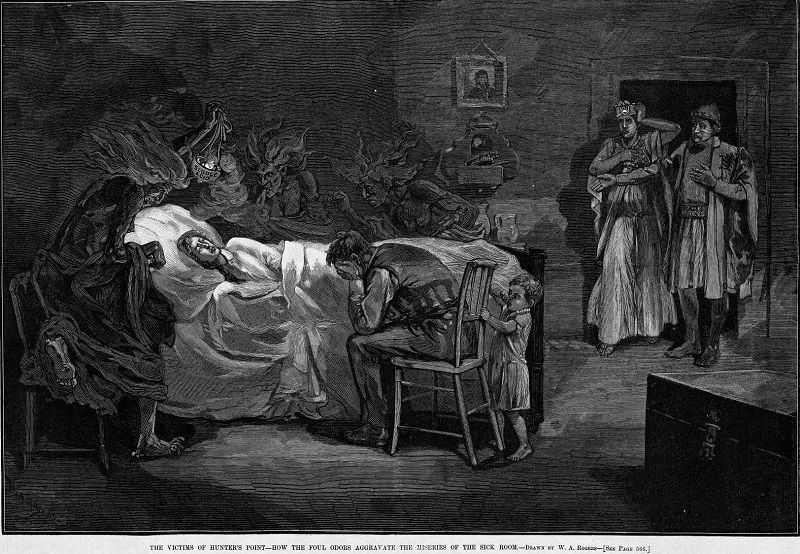

Harper’s Weekly, 20 August 1881, by W.A. Rogers

As shown in the cartoon above, Harper’s Weekly focused not only on the effects on Newtown Creek but on the air pollution that impacted health in surrounding areas including Manhattan’s East Side. The editorials called the businesses of Newtown Creek ” brutal bullies” who “poison the air which a large part of the city breathes.” “He who injures or annoys hundreds of thousands of his fellow-citizens will deserve and receive his punishment,” the magazine wrote, “as certainly as the ruffian who robs or kills the few.”

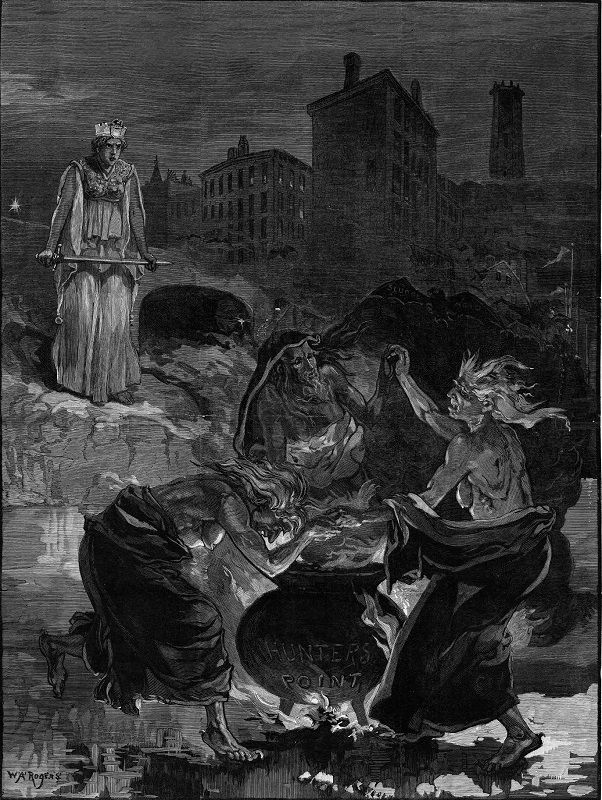

Harper’s Weekly, 13 August 1881, by W.A. Rogers

Another Harper’s Weekly cartoon, shown above, “Death Cauldron at Hunter’s Point” by W.A. Rogers, features demonic figures around the Hunter’s Point cauldron with sludge acid, embodied in a bat, hovering above. In a 21st-century echo of this hellish imagery, Mitch Waxman, who leads tours of Newtown Creek, refers to it as the “Poison Cauldron.”

Harper’s Weekly, 6 August 1881

Although bold in rhetoric, Gov. Cornell’s proclamation yielded no long term benefit. Business as usual continued for the most part and similar initiatives by other governors in 1883 and 1894 also had little effect. The New York Times ruefully observed in 1886 that “the nuisances of Newtown Creek for years have defied the power of the local authorities and of the State.”

In fact, the polluting of Newtown Creek went on for decades, including approximately 30 million gallons of leaked oil. To add insult to injury, the industrial contamination was exacerbated by discharge of municipal sewage. It was not until legislation such as the Clean Water and Clean Air Acts of the 1970s and Superfund in 1980, that problems such as this could start to be addressed in earnest.

But by then, the damage was done. The EPA, which added the creek to the Superfund list in 2010, states that “Newtown Creek is one of the nation’s most polluted waterways.” And although EPA is carrying out a cleanup, challenges remain, including discharges of untreated sewage from combined sewer overflows during heavy rainstorms.

As for the 1881 efforts, what lessons can we learn from the failure to protect Newtown Creek?

At the very least, it seems clear that Gov. Cornell, Harper’s, and other decrying the conditions at Newtown Creek reflected the public mood of the time.

All of this archival material contradicts the conventional wisdom that years ago few cared or understood about the need to protect public health and the environment. People in 1881 may not have had the scientific knowledge that would later inform the environmental movement, but they understood viscerally that foul odors, dense smoke, and dirty water were unhealthy and that industry, driven by competitive pressures, could not be left to regulate itself. It’s a lesson worth remembering.

Next, read about Chance Ecologies – documenting the last days of Hunters Point South before its redevelopment and the digester eggs of the Newtown Creek sewage treatment plan. Contact the author @Jeff_Reuben

Subscribe to our newsletter