Fiber Arts Take Over a Former Seaport Warehouse in NYC

See waterfalls of fabric, intricate threadwork, massive tapestries, and more!

Find out how you can visit the picturesque site that attracted artists and writers from NYC!

The Bush-Holley House, a colonial saltbox on the shore of the Mianus River in Greenwich, Connecticut, provided the perfect escape for artists and writers seeking respite from New York City in the mid-19th century. Set on a hill, the home became the birthplace of the Cos Cob Art Colony, a gathering place for painters and writers who sought to capture the idyllic village's quaint homes, bustling harbor, and serene pastoral scenes. Though the surrounding views have changed drastically since the 19th century, visitors can still explore the home and grounds where artists sought inspiration, and see the works they created at the Greenwich Historical Society.

The Bush-Holley House, as it's known today, is a National Historic Landmark originally constructed as a one-room, two-story structure between 1728 and 1730. Wealthy Greenwich farmer and town selectman Justus Bush later built the main “salt box” home and passed the property to his son David.

David brought grand changes to the hilltop site when he joined the two original buildings, added a new entrance hall, and finished the home with opulent details like floor-to-ceiling wood paneling. As the property passed through subsequent generations of the Bush family, various outbuildings were constructed and more changes were made.

After the Bush family, the next owners of note were Josephine and Edward Holley. The Holleys ran the home as a boarding house for artists and writers beginning in 1882. The affordable room and board and picturesque location attracted creative types from nearby New York City and created a welcoming bohemian atmosphere which spurred the formation of an art colony.

Impressionist painter John Henry Twachtman was drawn to the natural beauty of Cos Cob. On the shores of the Mianus River, he could paint bucolic scenes en plein air, just as he did with an informal art colony outside Paris, without having to travel a far distance. He moved to Cos Cob in 1890 and began offering summer painting classes. Students who traveled to study with Twachtman found rooms in the Holley boarding house.

In 1892 Twachtman was joined by painter J. Alden Weir and together they taught a summer class for the prestigious Art Students League. Removed from the scene in New York City, the teachers had more freedom to break from tradition and introduce new theories and methods of Impressionism.

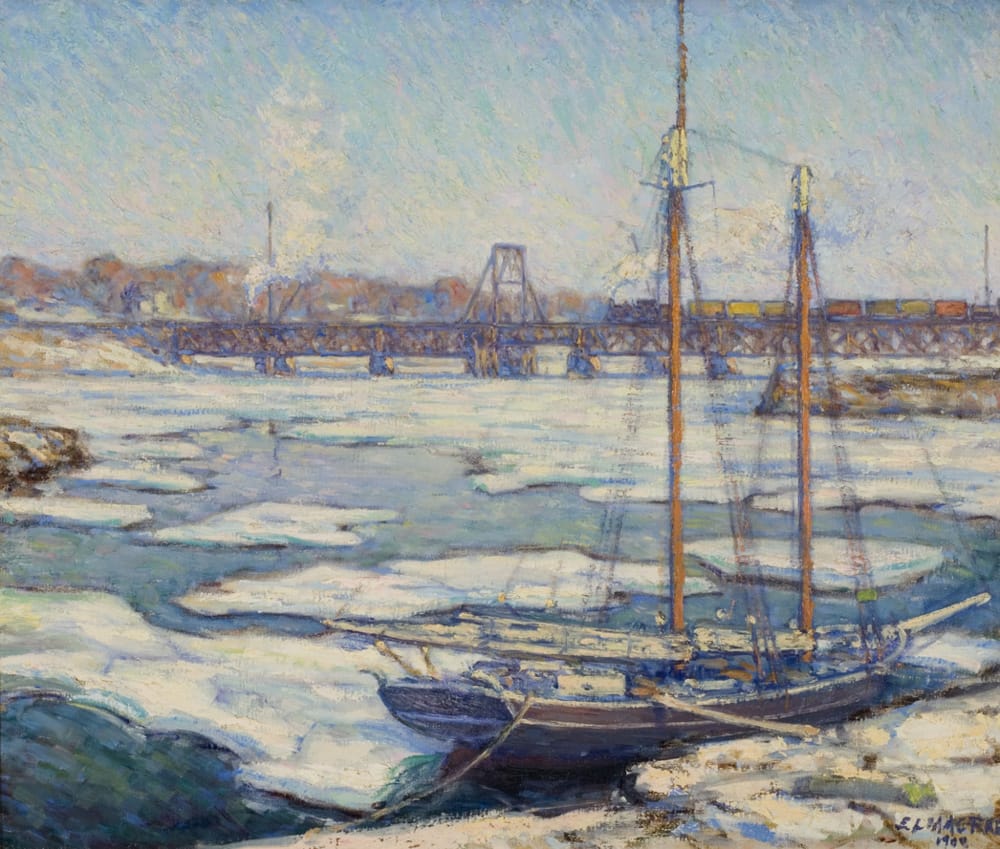

Impressionism was an emerging art form from France. It is characterized by broad brushstrokes, vibrant colors, and an emphasized use of light. The historic architecture, waterfront scenes, and coastal light of Cos Cob Harbor as well as the lush gardens of the Holley house, served as a perfect setting for this style of painting.

The art colony attracted a diverse array of painters, writers, and journalists. Some of the students included painter Childe Hassam, Theodore Robinson, Walter A. Fitch, George Wharton Edwards, Ernest Lawson and Genjiro Yeto, writers Lincoln Steffens and Willa Cather, and more. Hundreds of creatives found refuge in the art colony from the 1890s to the 1920s.

Journalist Lincoln Steffens wrote fondly of his time with the art colony in an essay from his 1934 autobiography, noting, “Cos Cob was a good place to think.” He found the activities in Cos Cob such as sailing and gardening helped calm his mind of troubles in New York and Chicago. He described the scene as a “paintable spot frequented by artists who worked, painters who actually painted” and “writers who wrote.” Of these fellow creatives he stated, “Even the arty people, who always follow artists as flies follow cattle, did not only talk and yearn for expression, but labored at their own chosen crafts which did not choose them…we talked art, and we had a contempt for people who talked business and politics.”

Another one of the young students drawn to the art colony was Elmer Livingstone MacRae. An Arts League student, he traveled from New York to Connecticut in the summer of 1896. In addition to practicing his art that summer, he also fell in love with Constant Holley, the daughter of the boarding house proprietors.

The couple was married in 1900 and MacRae set up an art studio inside the home. Constant featured frequently in his paintings, which you can still see hanging in his studio today alongside some of his original supplies. MacRae lived in the home until his death in 1953.

After Twatchman's death in 1902, MacRae continued to foster the art colony community alongside his wife. MacRae would go on to be a founding member of the Association of American Painters and Sculptors in New York, an organization that was instrumental in planning the International Exhibition of Modern Art (The Armory Show) in 1913 which introduced modern European artists such as Cezanne, Matisse, and Picasso. Members of the Cos Cob art colony also formed the Greenwich Society of Artists, which still exists today as the Greenwich Art Society.

You can see works by artists from the colony at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, and other illustrious institutions. Many are on display right where they were created, on what is today the campus of the Greenwich Historical Society.

(Left) Dutch Door by Childe Hassam (Right) Elmer Livingston MacRae (1875-1953) Schooner in the Ice, 1900, Oil on canvas. Courtesy of Greenwich Historical Society

On April 5th and 6th, Untapped New York and Greenwich Historical Society will host the grand opening of Re-Framing 95, an interactive art installation by Untapped New York's Artist in Residence Aaron Asis, inspired by the spirit of the art colony.

On display, visitors will see works by the original art colony painters, but with a notable change. Asis has added the I-95 highway which now runs in front of the Bush-Holley House. In addition to these paintings, the campus will be dotted with floating frames that highlight historic elements and vistas that may be considered “ruined” by the presence of the noisy highway.

By shifting the viewer’s attention to a piece of the scenery we might otherwise consider mundane, the installation inspires us instead to look at it as an important piece of history and recognize that history isn’t done being made.

This post contains affiliate links, which means Untapped New York earns a commission. There is no extra cost to you and the commissions earned help support our mission of independent journalism!

Subscribe to our newsletter