Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

New York City’s lost opera houses are having their fifteen minutes of fame, thanks to the HBO show, The Gilded Age, which brought their dramatic histories to life in the most recent season.

New York City’s lost opera houses are having their fifteen minutes of fame, thanks to the HBO show, The Gilded Age, which brought their dramatic histories to life in the most recent season. We dug into these former opera houses in a new extended episode of the Untapped New York podcast which weaves in clips from The Gilded Age, which were kindly provided to us by HBO. You’ll hear a conversation between Untapped New York founder Michelle Young and Justin Rivers, who recently gave a talk on this subject for our Insiders, along with excerpts from his talk. It’s kind of like The Ted Radio Hour, but for obscure New York City history.

We’ll cover some of the earliest opera houses (some of which where were Italian!), the Astor Place Opera House which inspired one of the deadliest riots in the city’s history, the Academy of Music, the first Metropolitan Opera House, and our backstage tour of the current Met Opera. You can follow along with this podcast episode using the visuals below.

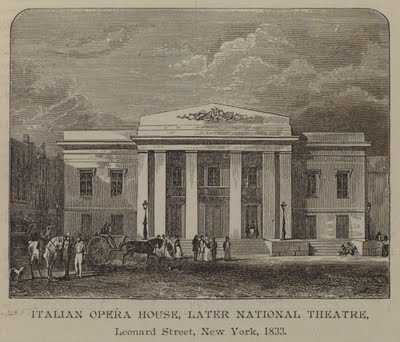

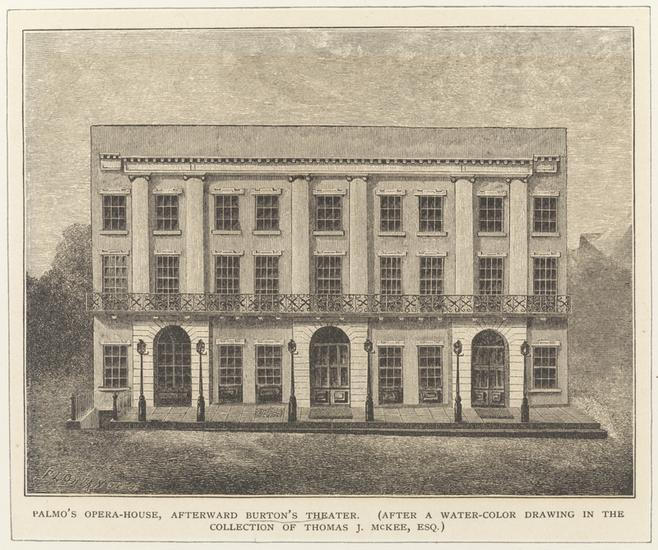

The Italian Opera House and Palmo’s Opera House (below) were the two first purpose-built opera houses, meaning, designed and used specifically for opera. Prior to that, there were other venues used for opera, which included Castle Clinton and Niblo’s Garden. These early opera houses, though interesting historically, were not successful, mainly because they failed to cater to the right crowds.

The Italian Opera House was located on the northwest corner of Leonard and Church streets in what we would know today as Tribeca. Architecturally, the Italian Opera House looked akin to a small White House. It was built by Venetian-American Lorenzo de Ponte, who was a Roman Catholic priest and librettist for Mozart. He emigrated to America in the late 1820s, became the first professor of Italian literature at Columbia University, and founded the Italian opera house in 1833, at the age of 84. It was a short-lived venture.

Palmo’s Opera House was located on Chambers Street, between Broadway and Centre Street. It was founded by Ferdinand Palmo, who hoped to bring Italian opera back, after the failure of the Italian Opera House. There was one major problem with this 800-seat opera house—extremely hard benches with a slat across the back. These were very uncomfortable for the long operas and the upper classes were disappointed in the lack of luxury. Palmo did allow them to upholster their own benches or bring a pillow, but the opera house only lasted about two seasons.

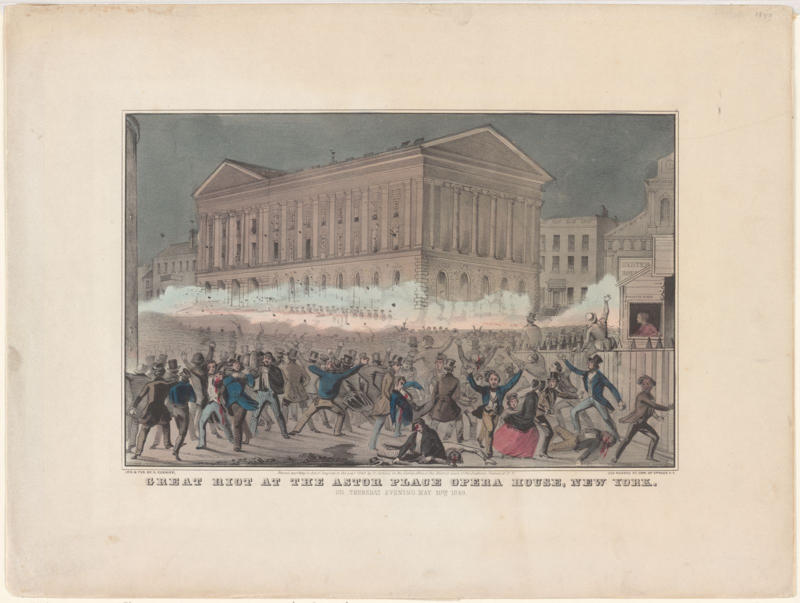

The Astor Place Opera House is the first of the big purpose-built opera houses and one of the most famous of the lost opera houses. As its name suggests, it was located at Astor Place, on the wedge of land bounded by Lafayette Street, East 8th Street and St. Mark’s Place. The Astor Place Opera House was conceived by a man by the name of Edward Frey, an impresario who managed the opera house during its entire, short-lived history.

The Astor Place Opera House debuted on November 22, 1847 with a performance of Giuseppe Verdi’s Ernani, which was very well-received and very well-reviewed. Later on, the Astor Place Opera House debuted Verdi’s Nobuko in 1848. Verdi’s operas, and five other operas will have their American debuts at the Astor Place Opera House. The opera house will however become infamous in New York City history because of the riots that took place there, one of the deadliest in New York City history. .

At a time of high tension between the haves and have-nots in America, two theater actors are booked on the same night to play Shakespeare’s Macbeth: American actor Edwin Forrest and English actor William Macready. Working-class New Yorkers were encouraged to come and protest at the Astor Place Opera House a few days after the doubleheader. 10,000 people filled the streets around the opera house, none of whom were ready to protest peacefully. With the rallying cry of “Down with the codfish aristocracy!”, they brought rocks and bottles to use as projectiles at audience members and anybody trying to stop them.

The New York City Police Department knew right away that they were not going to be able to handle it, so the New York State militia was brought in. At first, they formed a line and shot up straight into the air without injuring anybody. But then without warning, they turned their guns on the participants and started firing. There were casualties of some kind on all sides, including police, militia, and innocent bystanders. It was said somewhere between 22 and 31. rioters were killed that evening, and 48 were wounded. Somewhere between 50 to 70 policemen were injured. 141 of the militia were injured, mainly by rocks and bottles being thrown at them. Incredibly, the demise of the Astor House Opera House came not at the hands of Shakespeare, but by monkeys, Listen to the podcast episode to learn more about its fate.

The Academy of Music was located on 14th Street and Irving Place and catered to wealthy New Yorkers, who were migrating uptown. The Corporation for the Academy of Music was created by a former New York Congressman by the name of Moses Grinnell, who sold $1,000 shares to wealthy New Yorkers, which got each of them a box in the opera house and a seat on the board of directors. The construction cost of the building at the time was upwards of about $400,000.

At first, the founders hoped to make the venue less stuffy than the Astor Place Opera House, but they failed at that almost immediately. The debut opera was Vincenzo Bellini’s Norma and The Academy of Music became an institution overnight. It was a versatile space that could be used not only for opera, but also for balls and receptions. Notable patrons included the Prince of Wales, Abraham Lincoln, and his wife Mary Todd. It was a place to see and be seen, with the patrons much more interested in observing each other than watching opera.

The Academy of Music faced an existential crisis with the rise of the nouveau riche in 1870s New York. The new captains of industry—from oil, rail, and shipping like the Vanderbilts and the Morgans wanted boxes at the Academy of Music, but there simply were not enough boxes for them. Instead of waiting endlessly for their turn, 25 captains of industry decided to form a new opera house, to be called the Metropolitan Opera House. It was set to debut on the same day as the Academy of Music in 1833.

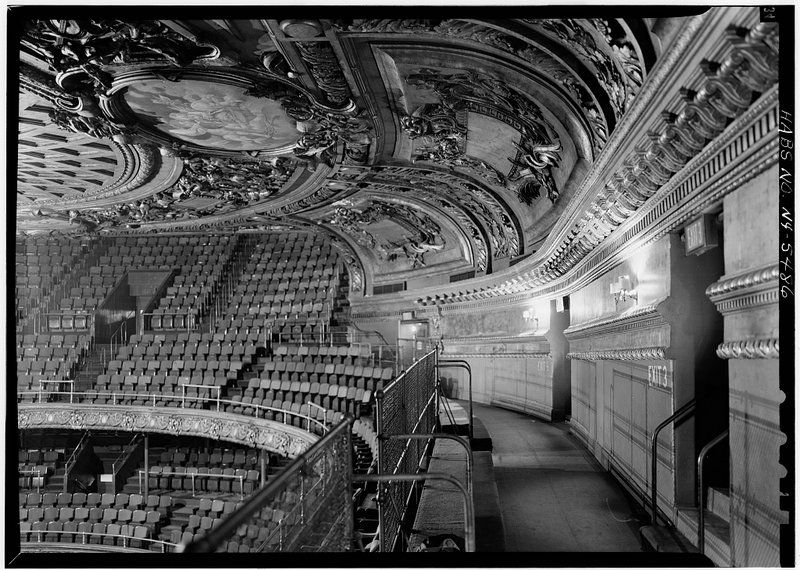

The “Old Met”, the last of the grand lost opera houses in New York City, was located between 39th and 40th streets between Broadway and Seventh Avenue. The architect, J. Cleveland Cady was responsible for the design of the building in 1883. The major funders of this new enterprise were James Roosevelt, uncle of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, William K. Vanderbilt, Cornelius Vanderbilt, Robert Ogden, and Pierpont Morgan. They and others lent $15,000 per shareholder with an anticipated cost of $600,000. That figure soared to 1.5 million.

The Metropolitan Opera House could seat 4,000 opera-goers, twice the capacity of The Academy of Music. The performance space itself was also much more grand—the stage was 92 feet deep and 100 feet wide, with the largest proscenium in the United States at the time. And, it was specifically designed for people to watch each other, with what was known as the “Golden Horseshoe”—two levels of ornately decorated boxes. which were facing each other. It fell victim to fire in 1892 but was rebuilt by Carrère and Hastings, who also designed the New York Public Library, to make it even more golden than before. Even so, the Old Met will face the chopping block in the mid-20th century, a story detailed in both the podcast in a previous article. The new Metropolitan Opera will open at Lincoln Center in 1966.

There are even more lost opera houses in the podcast so listen to the full episode! Subscribe and listen to the Untapped New York podcast on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts! For more opera, join us on the spectacular Met Opera backstage tour:

Subscribe to our newsletter