100th Anniversary Great Nave Tour at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine

Celebrate the 1925 construction of the stunning nave inside the world's largest Gothic cathedral!

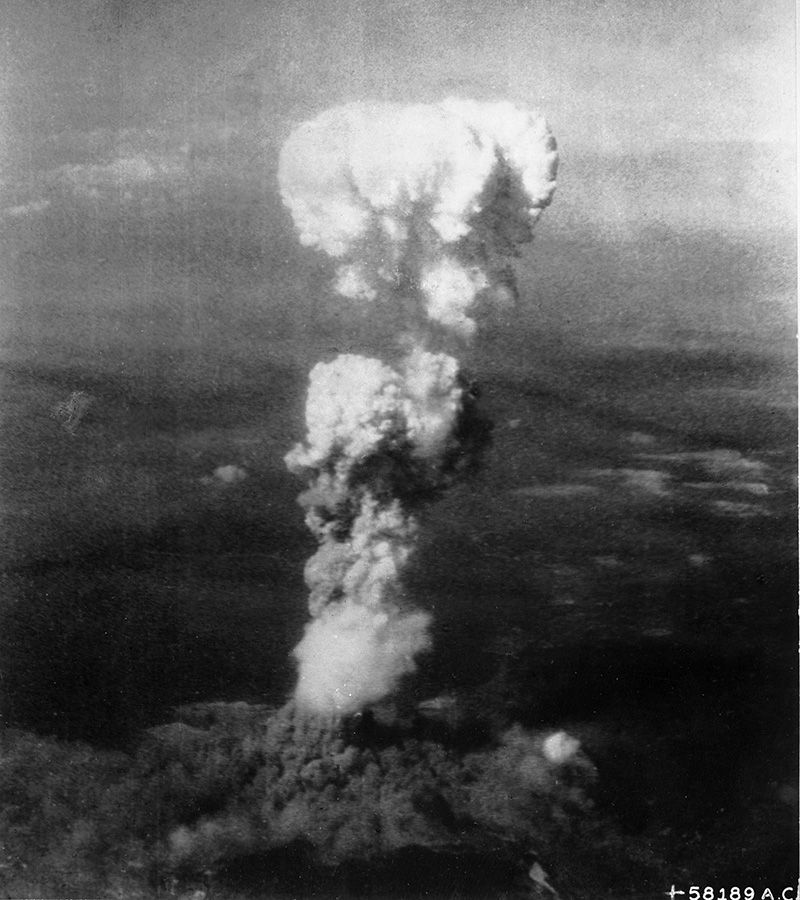

August 6th marks the day that the United States dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Japan. Three days following the initial atomic bombing that killed an estimated 66,000 people on impact and injured another 69,000, the U.S. dropped a second atomic bomb on Nagasaki, Japan. This bomb would kill 39,000 on impact. Six days after the second deadly bombing, Emperor Hirohito surrendered, effectively ending World War II. However, the journey toward these fateful days took a significant step on December 28, 1942, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt approved the Manhattan Project. Although the name of the project hid its end goals — to develop a nuclear weapon for the United States — it did not mask a primary research location: New York City.

Lieutenant General Leslie Richard Groves, Jr. directed the Manhattan Project. Born in Albany, the Lieutenant officially named the project the Manhattan Engineer District. This followed the practice that Corps of Engineers districts were named after their primary research city. The project’s first offices were located at 270 Broadway, although they quickly expanded across the city.

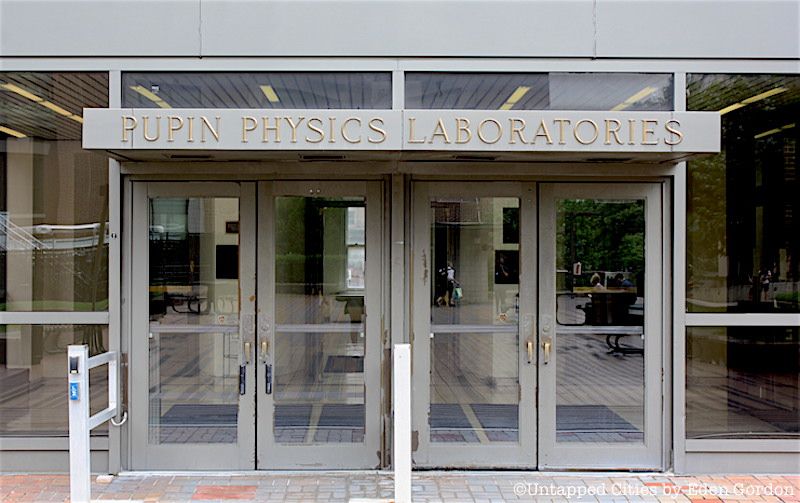

Naturally, researchers moved to Schermerhorn Hall and Pupin Hall at Columbia University — the location where Professor John R. Dunning and his team created the Cyclotron. This device performed nuclear fission until it was decommissioned in 1965. Using the Cyclotron and the combined expertise of scientists including Isidor I. Rabi, Enrico Fermi and Dunning, the team mastered the “gaseous diffusion” method of separating uranium isotopes. This method enabled Manhattan Project scientists to collect uranium-235, a key element of the atomic bomb. Following World War II Columbia, built another nuclear testing facility in Prentis Hall which was operated under the “Atoms for Peace” program and used to test nuclear reactor fuel assemblies.

As their research expanded, so did the space Columbia University researchers needed to occupy. The University purchased the Nash Garage Building that was located at 3280 Broadway. In this building, researchers including Lawrence S. O’Rourke — an engineer recruited from the Army Corps — created barrier material for the K-25 plant in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. With a well-designed barrier, scientists at the plant could safely separate uranium isotopes in mass quantities. Other precautions included a leak detector and careful cleaning of each part within the plant. The Kellex Corporation — a corporation designed by the M.W. Kellogg Company to keep their work secret — designed the K-25 plant. Their headquarters were in the Woolworth Building, constructed by Five-and-Dime millionaire Frank Woolworth.

Other Manhattan Project stations were scattered throughout the city. The Baker and Williams Warehouses stored uranium concentrates along W. 20th Street. Conversely, the Madison Square Area Engineers Office employed those in charge of locating materials necessary for the atomic bomb.

Other than New York City, Manhattan Project facilities were also located in New Mexico, Tennessee, Illinois and Washington. Primary research moved to the University of Chicago due to fears that the Germans would bomb Columbia University from the Hudson River. In Chicago, researchers achieved the first self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction,

With so many people involved in the secret project, few knew what the culmination of their work would look like. However, some research fell through the cracks. David Greenglass, a Russian spy, testified that he sent information to his brother-in-law and New York native, Julius Rosenberg. As a machinist and member of the Special Engineer Detachment in Los Alamos, New Mexico, Greenglass had vital information about the explosive lenses that detonated the plutonium core in the atomic bomb.

In the trial that ended in the execution of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, Greenglass said he sent Rosenberg typed information about the bomb along with a rough sketch to send to the Russian government. Some say he aimed to protect his wife when he blamed his sister Ethel for typing the notes. Greenglass claimed the Rosenbergs recruited him to join their espionage activities. After the jury found the Rosenbergs guilty, they were executed by an electric chair in Sing Sing Prison. Since the couple was involved in leftist political and labor efforts preceding their death, some say they were used as a scapegoat for preliminary Red Scare hysteria. They never admitted to passing on information to Russia, which was an ally to America at the time.

Despite any alleged espionage surrounding nuclear research, Manhattan Project researchers tested a plutonium implosion device on July 16, 1945. This explosion, which occurred 210 miles south of Los Alamos, New Mexico, was the first nuclear explosion and occurred only weeks before the U.S. would drop a fully-operating atomic bomb on Hiroshima.

Without testing the final product, Manhattan Project scientists were confident the “Little Boy” gun-type uranium bomb would explode upon impact. Pilots of the Enola Gay plane — Colonel Paul Tibbets and Captain Robert Lewis — flew the 9,700-pound atomic bomb to Hiroshima. On August 6, 1945, at 8:15 a.m., they dropped the bomb from 31,000 feet in the air,

Almost 80 years since that fateful morning, the world pauses on August 6 to remember the thousands who died from the first atomic bombing. In Hiroshima, the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park honors those who died during the world’s first nuclear attack. The park highlights the Atomic Bomb Dome, a building that survived the atomic bombing despite being near the center of the explosion. It is in front of the dome that hibakusha — survivors of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bombings — gather annually on August 6 to remember a day that would change the rest of their lives. As survivors of the only atomic attacks in history, they hope to prevent another deadly atomic attack from occurring in the future.

In New York City, the Shinran Statue reminds all who pass it about the effects of nuclear war. The Japanese initially offered this statue that survived the Hiroshima atomic bombing to the United Nations as a symbol of peace. The United Nations placed the statue in front of the New York Buddhist Church, where it now stands at 105th Street and Riverside Drive. Red burn marks remain on the statue’s robe as a result of the atomic bomb’s radioactive blast.

A few other reminders of the Manhattan Project exist throughout New York City. The Noguchi Museum contains Isamu Noguchi’s Memorials to the Atomic Dead, created “as a significant protest against the Bomb.” Columbia University dismantled the Cyclotron and donated it to the Smithsonian Institute in 1965. Some speculate the University attempts to hide its relationship with nuclear history. There have been no recent exhibits about Columbia University‘s involvement in the Manhattan Project, and other buildings involved in the Manhattan Project remain as nondescript as they were during World War II.

Despite efforts to hide the research that led to the first atomic bombing, New York City and the world continue to inch closer to nuclear winter. The Doomsday Clock is a metaphor that reminds all “how close we are to destroying our world with dangerous technologies of our own making.” We are 100 seconds to midnight, or destruction. The Non-violence sculpture in the United Nations sculpture garden reminds all to travel further from midnight, signifying that humanity should hope for peace rather than victory.

Next, check out the story of Untapped Cities Founder Michelle Young’s grandfather, who survived the atomic bombing at Hiroshima.

Subscribe to our newsletter