100th Anniversary Great Nave Tour at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine

Celebrate the 1925 construction of the stunning nave inside the world's largest Gothic cathedral!

When the first atomic bomb was dropped on the Japanese city of Hiroshima on August 6th, 1945, followed by a second bomb in Nagasaki three days later, the world was forever changed. Before the atomic bomb became known to the world, however, its creation was shrouded in secrecy. Though The Manhattan Project is no longer secret, the places in New York City used for research, uranium storage, and other clandestine activities are not as well known. Manhattan Project isn’t a codename, rather it was issued using standard Army Corps of Engineers naming practices which were based on primary research locations. Lieutenant General Leslie Richard Groves, Jr., director of the project, came up with the name Manhattan Engineer District, which was plain enough to not attract attention. It was then naturally shortened to the Manhattan Project. As the project grew, research, testing, and construction spread out to other areas of the country, mostly notably Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and Los Alamos, New Mexico. The earliest days of the project however were based right here in New York City.

This weekend, as Christopher Nolan’s summer blockbuster Oppenheimer continues to play on theater screens, the world will mark the 78th anniversary of the bombings at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Here, we uncover 8 sites connected to the Manhattan Project and the tragic events of August 6th and 9th, 1945.

In 1942, the 18th floor of 270 Broadway is where the first offices occupied by engineers on the Manhattan Project were located. This is where the North Atlantic Division of the Army Corps of Engineers was headquartered at the time and where the project got its name. Built in 1930, the building is now occupied by office, retail, and residential spaces. In 1943, the headquarters of the Manhattan Project moved to Oak Ridge, Tennessee.

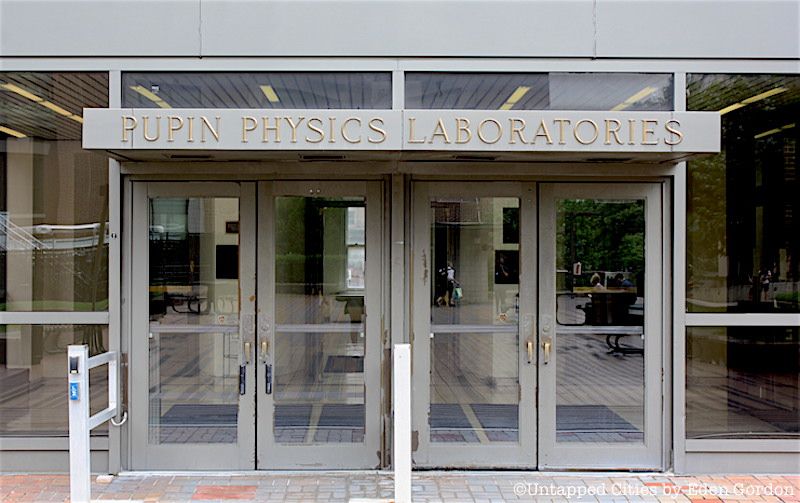

Multiple buildings throughout the Columbia University campus were used by Manhattan Project members. Schermerhorn Hall and Pupin Hall saw the creation of the Cyclotron by Professor John R. Dunning and his team. This device facilitated nuclear fission and is now housed in the collection of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. When researchers needed even more space, the University purchased a former car dealership at 3280 Broadway. Known as the Nash Garage Building, it was used by researchers such as Lawrence S. O’Rourke who worked on creating a barrier material for the K-25 plant in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. After World War II. Columbia’s Prentis Hall was used as a nuclear testing laboratory. Tests conducted there were part of the “Atoms for Peace” program.

The Kellex Corporation had its headquarters inside the Woolworth Building, a 1920s skyscraper in Lower Manhattan constructed by Five-and-Dime millionaire Frank Woolworth and dubbed “The Cathedral of Commerce.” The Kellex Corporation was a clandestine off-shoot of the M.W. Kellogg Company, a chemical engineering company based in Jersey City. The company was chosen to design the K-25 plant in Tennessee and to develop processes and equipment to produce enriched uranium through gaseous diffusion. The K-25 name for the Oak Ridge site took its “K” from “Kellog” and “25” from the type of uranium used in the project.

The Baker and Williams Warehouses on West 20th Street were used temporarily to store tons of uranium concentrates. The uranium came from the Eldorado Mining and Refining Limited Company in Canada and arrived in secret at the Hudson River’s docks. Remediation of the warehouses took place from 1991 to 1993.

In New York City, in addition to sites connected to the Manhattan Project, there are also places where you can remember those who were tragically affected by the bomb’s destructive force. The Shinran Statue stands on 105th Street and Riverside Drive as a memorial to those lost in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The statue is one of the few artifacts that survived the bombing of Hiroshima and it was brought to the U.S. in 1955. It now stands in front of the New York Buddhist Church where an annual remembrance service is held every August. You can also honor the memory of the bombing victims at The Noguchi Museum where you’ll find Isamu Noguchi’s Memorials to the Atomic Dead sculpture.

South of the Buddhist Church is the childhood home of J. Robert Oppenheimer, the Manhattan Project’s Chief Scientist. Oppenheimer lived with his parents and brother Frank on the 11th floor of this building on West 88th Street. His father was a German immigrant who had success in his family’s textile business, while his mother was a painter with deep roots in New York City. Oppenheimer attended school on the Upper West Side at the Ethical Culture Society School, before going on to study at Harvard.

Belgian immigrant Edgar Sengier, the director of Union Miniere du Haut Katanga, kept his office inside the Cunard Building at 25 Broadway. Union Miniere du Haut Katanga was a Belgian mining company that operated in the Democratic Republic of the Congo during the first half of the 21st century. During World War II, Sengier feared that the Axis powers would capture the precious uranium ore the company extracted, so he had multiple tons of it shipped to the United States. Some of this ore ended up in a warehouse on Staten Island owned by The Archer Daniels Midland Company. The warehouse was located at 2351 Richmond Terrace below the Bayonne Bridge.

Uranium ore was stored at this waterfront site from 1940 until 1942 when it was purchased by the Manhattan Project. The warehouse was then torn down. Radioactive contamination was discovered at the site by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) in 1980, but it wasn’t until May 2020 that The Archer Daniels Midland Company/Manhattan Project site finally made it into the Department of Energy’s Formerly Utilized Site Remedial Action Program. The program “identifies and remediates sites contaminated as a result of the country’s early atomic energy program in the mid-20th century.” Awareness of the Archer Daniels site is largely thanks to the efforts of Beryl Thurman, president, and executive director of the North Shore Waterfront Conservancy (NSWC).

Next, check out the story of Untapped Cities Founder Michelle Young’s grandfather, who survived the atomic bombing at Hiroshima.

Subscribe to our newsletter