Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

New York Transit Museum has opened Meet Miss Subways: New York’s Beauty Queens 1941-76, an exhibition on the history of this unusual pageant that advertised itself in the subway system for 35 years. At the opening, photographer Fiona Gardner and journalist Amy Zimmer were on hand to discuss the genesis and evolution of their project, along with four former Miss Subways.

The contest, run by New York Subway Advertising, was a way to improve sales by directing bored commuters’ eyes to photographs of smiling, attractive women strategically placed next to tobacco and chewing gum advertisements. Originally constructed as an application process, in 1963 the selection was opened up to popular vote with finalists and then winners displayed on posters in the subway cars.

Gardner discovered this lost little bit of New York history many years ago, and did the bulk of the research, tracking down former Miss Subways and photographing them. Zimmer interviewed the women, and extracts of her conversations are featured on wall labels next to Gardner’s contemporary photographs of the women in their current lives.

The juxtaposition of these women’s original ideas of their lives and their current existence traces a fascinating story of the evolution of women’s rights over the past 60 years. Gardner said that she wanted to emphasize “what represents the women now,” focusing on “this point in their lives” instead of their twenty-something self from the advertisements. She created portraits of them on her Hasselblad camera, in photographs that emphasize intimacy and locality: some women are shown in their homes or apartment buildings, others at their neighborhood transportation stations.

The exhibition is careful to portray the contest as well as it can, while not shirking from some of the underlying implications. It is notable, and commendable, that although the vast majority of Miss Subways were white, African-American Thelma Porter and Asian-American Helen Lee were both winners in the 1940s–a period not known for its progressive race relations. A more problematic aspect is the copy in the biographies themselves.

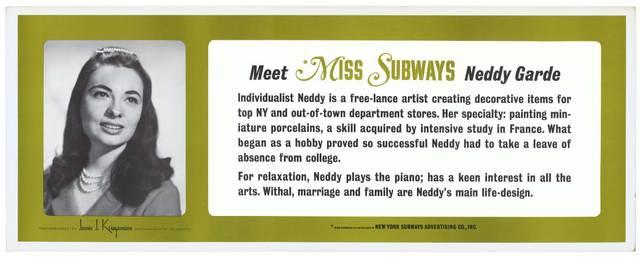

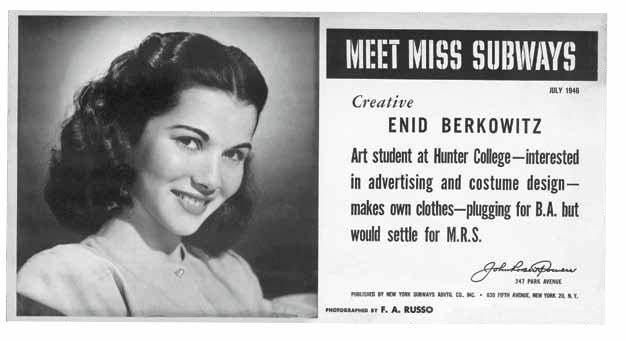

Although the NYTM exhibition notes that eventually more attention was paid to the women’s aspirations and career goals, that “more attention” is only apparent compared to most of the placards in the show, which read like G-rated personal ads. Contestants like music and pets; they volunteer and audition; they love family and want one of their own. Some of my favorite lines include “Withal, marriage and family are Neddy’s main life-design” and “plugging for B.A. but would settle for M.R.S.”

That last line was featured on the placard of Enid Berkowitz (now Schwarzbaum), Miss Subways in July 1946, and based on the delightful time I spent with her I gathered that it wasn’t her idea! Gardner’s portrait of Enid shows her surrounded by her own art, including a painting called The Golden Age of Chivalry which features Albrecht Durer’s Adam from 1507 proffering his apple to Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini lady from 1434.

The irony implicit in this depiction of male-female relations was also evident in conversation with Enid, who was impatient to talk about things other than her moment of subway glory over 60 years ago. “It was lovely, it was fun, it was history,” she said. “It wasn’t an accomplishment, I was lucky to have good-looking parents. My work, my art””that’s an accomplishment.”

When I asked Enid if she was surprised when she heard from Gardner and Zimmer she replied that she was, because the name under which she had been Miss Subways had disappeared 63 years ago, when she married. We talked avidly about her family, art history, and feminism, and the 86-year-old evinced passion and charisma that was missing from her description in 1946.

The spry and elegant Enid, a living embodiment of the NYTM’s exhibition, was a powerful reminder that behind the silly copy of the subway placards were real women, who were molded temporarily to fit an advertising agenda, but had their own complicated relationships and roles that no one in the 1940s could have seen coming. And that is the most important part of Meet Miss Subways as a signpost exhibition””look how far we’ve come; look how far we have to go.

Get in touch with the author @kaygegay

Subscribe to our newsletter