Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

The MetLife Building sky bridge just next to Madison Square Park is being demolished. Photographer Klaus-Peter Statz, one of our Untapped New York Insiders recently sent us a series of images, writing “Living not too far from the sky bridge on East 24th Street (between Madison and Park) I noticed that there is work underway that looks a lot like the sky bridge is being demolished. Google doesn’t provide any clues. I saw that Untapped New York featured the bridge a while ago in an article. As you guys are usually well-informed, would you happen to know what’s going on?” Indeed, we were able to confirm with a press spokesperson for SL Green, the owner of the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company buildings at 1 Madison Avenue and 11 Madison Avenue, that the Art Deco-period sky bridge that connects them is indeed in the midst of demolition.

Workers at the MetLife Building sky bridge on October 24th. Photos by Klaus-Peter Statz

The sky bridge was made of stainless steel with glass windows and a geometric grid-pattern windowpane in each. On October 24th, Statz documented workers on the bridge cutting square pieces of the steel out and removing the pieces one by one, from south to north. By October 27th, only the floor and the bottom arched portion of the sky bridge remained — the rest was supported by wood columns and panels. By November 9th, the center of the wood support structure was removed.

The MetLife Building sky bridge as of October 27th, 2020

The MetLife Building sky bridge on November 9, 2020

Sky bridge as of today, November 20, 2020. Photo by Chris Johanson @ctopher7

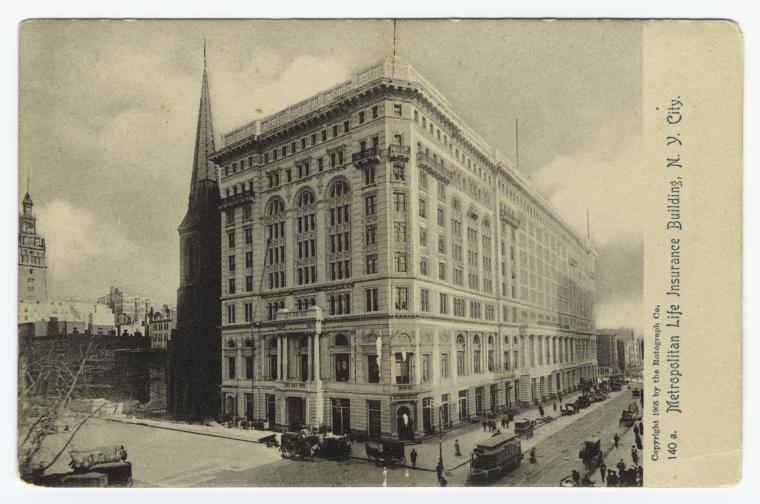

To better elaborate what’s going on, it’s worth looking at the architectural and real estate history of MetLife, which has been one of the largest land owners in New York City. The Metropolitan Life Insurance Company has existed since 1865, first under the name the National Union Life & Limb Insurance Company, and after a split into two companies, changed its name in 1868 to the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company, with a parent company known today as MetLife, Inc. First located in Lower Manhattan at 243 Broadway and 319 Broadway, the company had its longest presence along Madison Square Park, dating back to 1890 when it purchased a series of townhouses between 23rd and 24th streets on the east side of the park. Combining the lots, the company built its first headquarters “uptown,” a Tuckahoe marble-faced building designed by Napoleon LeBrun & Sons that rose eleven stories.

The Metropolitan Life Insurance Tower when it was the tallest building in the world. To the right is the Napoleon LeBrun & Sons-designed headquarters. Photo circa 1909-1915, source: Library of Congress

The rest of the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company headquarters was a complex of seven separate, but attached buildings on the superblock bounded by Madison Avenue and Park Avenue, and 23rd and 24th streets. The “South Building” and the “East Wing” look like one architectural idea, but was actually built over the course of sixteen years from 1890 to 1906 as the company gradually acquired more of the lots, including the old Lyceum Theater.

The original Madison Park Presbyterian Church with its Gothic steeple next to the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company building along 23rd Street and Madison Avenue. Postcard from 1905 from the NYPL Digital Collections.

Then, the tower was the last to be built because of a holdout: the Madison Park Presbyterian Church and its infamous reverend, the Dr. Charles H. Parkhurst would not sell. The church would finally be acquired in April 1906, when Parkhurst was offered a more spacious lot right across 24th street (which they will lose again, when MetLife expands yet again in the 1920s). The fifty-story tower, a slim and stately Italian-inspired skyscraper, was built between 1907 and 1909, and still stands tall over Madison Square Park today. It too would be designed by Napoleon Le Brun & Sons as well (Pierre Lassus LeBrun, specifically) and was modeled after St. Mark’s Campanile in Venice. It held the title for tallest building in the world from 1909 to 1913.

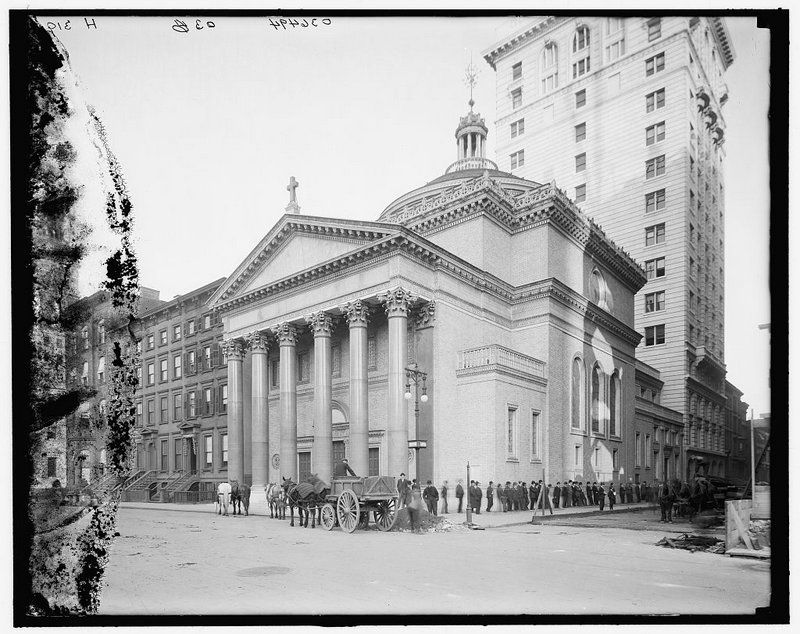

The north block, just north of the tower was acquired in the late 1920s. Above is a look at the buildings that were once on that block before 11 Madison Avenue was built. The new Madison Park Presbyterian Church is on the northeast corner of 24th Street. Photo from Library of Congress circa 1916.

Over the next two decades, space would become an issue again for Metropolitan Life. In the late 1910s, the company would acquire the new Madison Park Presbyterian Church, a Byzantine-style church designed by Stanford White, with sculptures by Adolph Weinman (who also created the eagles and other sculptures on the original Penn Station). The church would stand here just thirteen years, completed in 1906 and demolished in 1919 when the church merged with First Presbyterian Church. Metropolitan Life replaced it with a roughly 15-floor building. Most relevant to our story: an ornate sky bridge, located further west than the current sky bridge, was built connecting this new building to the Metropolitan Life offices in the south building.

The new Madison Square Park Presbyterian Church by Stanford White, built in 1906. Photo from Library of Congress, taken before the pediment sculptures were carved.

The original sky bridge across 24th Street. Photo by Wurts Bros. from NYPL Digital Collection.

To accommodate the growing company, the rest of the block between 24th and 25th streets was acquired starting in the late 1920s. As the New York City landmarks designation report for the tower indicates, “As work spaces expanded, the thick party walls [between the buildings between 23rd and 24th streets] may have become obstructions. By the mid-1920s a more centralized structure was needed to house the increasing divisions of a large corporation the size of Metropolitan Life.”

MetLife demolished its own building on the northeast corner of 24th Street and built the “North Building,” now known as 11 Madison Avenue, in 1932. It should be noted that a much grander structure was envisioned — something that would be the tallest building in the world at the time, enabling Metropolitan Life Insurance Company to regain the architectural title it held earlier in the century.

The new building was designed by D. Everett Wald and Harvey Wiley Corbett, a graduate of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts who went on to work for Cass Gilbert. Visionary drawings he made with Hugh Ferris helped illustrate what New York City could look like with the enactment of the 1916 zoning regulation, and put Corbett on the radar as an architect. Corbett left his job with Rockefeller to design the new Metropolitan Life Insurance Company building, envisioning something at 100 stories and nearly 1,500 feet tall. As Benjamin Waldman wrote for Untapped New York in 2014, the building “can be described as a cross between Gaudi and Art Deco (with a little Art Moderne thrown in). MetLife’s new building would have been mountainous.”

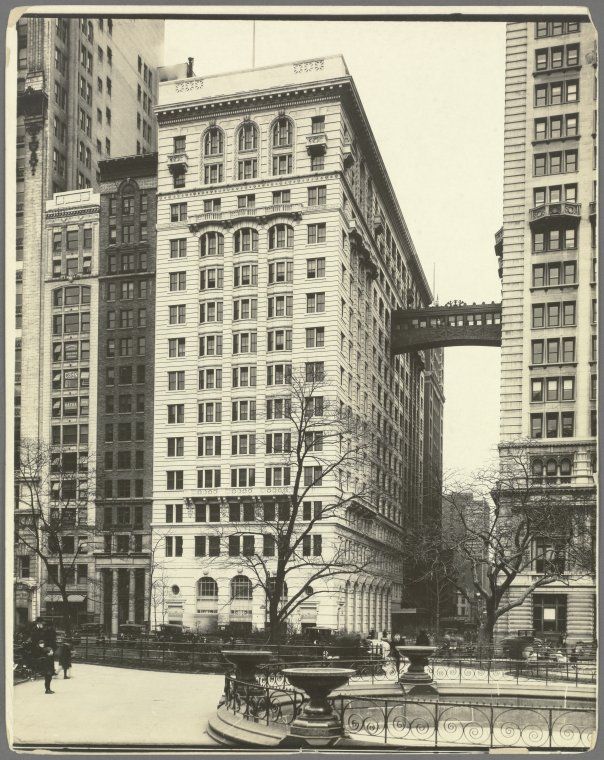

11 Madison Avenue, center, and tower at One Madison right

Construction began in 1928, but was never completed. While construction continued throughout the Great Depression, Black Tuesday took its toll. By 1933, construction was terminated and the building, as it was completed to that point, became the final version. That’s why, if you look at the 11 Madison Avenue building today, it has a flat roof — the 30-story building is merely the base of what might have been. Despite the halt in construction, a new Art Deco sky bridge was completed — echoing the original sky bridge across 24th Street in function, if not form.

The National Register of Historic Places designation form, which includes both square blocks of the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company complex, describes 11 Madison Avenue bluntly as a “severely simple 366 foot shaft.” One Madison Avenue and 11 Madison Avenue were connected by a sky bridge on the eighth floor (and via a tunnel underground), as confirmed by the National Register of Historic Places designation form, which also notes that “These are both considered non-historic features and are not counted” in the designation.

As for 1 Madison Avenue, it was not until the 1950s and 60s that the rest of the super block, apart from the tower, was reconfigured under the direction of architects Lloyd Morgan & Eugene V. Meroni, Architects. The result was an architecturally consistent building with a facade of ashlar limestone and setbacks that makes the building appear like it was designed in one-swoop. In reality, like before, the construction happened in phases, following the “system of internal light courts” that had existed in the original mishmash of buildings, states the Landmarks Designation report for the tower, and that “business continued in the old spaces before demolition and in the new as they became accessible.” This building was not landmarked when the tower was landmarked in 1989.

The developer SL Green purchased One Madison Avenue in 2005 directly from MetLife and purchased 11 Madison Avenue in 2015. Groundbreaking began on the redevelopment of One Madison just four days ago, on November 16th, in a ceremony attended by Mayor Bill de Blasio. The architectural firm leading the project is Kohn Pederson Fox (KPF). To fund the work, SL Green took a $1.25 billion construction loan and also sold a 49.5% stake in the building to Korea’s National Pension Service and the United States-based developer Hines. Korea’s National Pension Service is also a partner in SL Green’s other high-profile development, One Vanderbilt, which opened this September.

Rendering of the future One Madison, redeveloped by SL Green with Kohn Peterson Fox as architects. Image from SL Green.

One Madison Avenue will be the largest commercial development to start construction in New York City since March, the beginning of the pandemic. According to the press release, the plan is to “transform the existing full-block structure into a 27-floor, state-of-the-art office tower.” A new, 530,000 square foot tower will be added to the building “as of right,” meaning using available and undeveloped FAR (Floor Area Ratio) that is available to the site as part of its zoning. The facade will be opened up for larger ground floor retail windows and office windows on the upper floors. When completed, the building will have 1.4 million square feet of rentable square footage with amenities including outdoor roof terraces, event space, food market, lounge and fitness center for tenants.

Base of the future tower at One Madison. Image from SL Green.

The building’s design also responds to the most important health challenge of our time: coronavirus, by being the first multi-tenant office building to use DOAS HVAC, which according to SL Green “employs circulation of 100% outdoor, fresh-air thereby reducing employee sick days and increasing productivity.” The building will also be certified LEED-Gold and WELL, affirming what Mayor de Blasio stated at the groundbreaking, “We had to act here and we did, and SL Green and all the partners in this project are taking that idea and bringing it to life and proving that we can do something different and this city can be in the forefront of stopping global warming.” As part of the redevelopment, SL Green will also donate $250,000 to the Madison Square Park Conservancy to assist financially in the completion of the park’s dog run and in the ongoing maintenance and upkeep of the park.

The demolition of the sky bridge is a result of the construction of the new tower, and the developer SL Green contends that it was necessary due to the setbacks required. In a statement, SL Green explained, “The as-of-right zoning for One Madison dictates that the redeveloped tower is set back from 24th Street and therefore could not connect to the skybridge, requiring that the skybridge be removed as construction begins. These plans were presented to the Landmarks Preservation Commission, Community Board and preservationists last year.”

New Yorkers like Klaus-Peter Statz are expressing their sadness about the long-time neighborhood icon disappearing: “How can they destroy such an Art Deco masterpiece?” Statz asked in an email to us. Simeon Bankoff, Executive Director of the Historic Districts Council told us in an email, “New York is a vertical city and sometimes our landmarks are above street level. This is a real loss to our cityscape.”

That being said, neither building, One Madison nor 11 Madison Avenue is landmarked. Only the tower at the corner of 24th Street and Madison Avenue is. And as mentioned, although both square blocks of the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company buildings are listed on the National Register for Historic Places, the report specifically excluded the sky bridge from historic designation.

Go check out what’s left of the MetLife Building sky bridge before it disappears completely. In the meantime, for a look back, you can see photographs of the sky bridge over the years by Klaus-Peter Statz, the Untapped New York Insider that alerted us to the construction work.

March 2016

November 2015

Orange construction netting atop the skybridge in June 2013

August 2013

New York City’s sky bridges are those serendipitous delights you come across walking around, that remind you of the attention paid in the past that merged design. Despite this loss, many sky bridges still remain in New York City, and a new one was even built as part of the American Copper Building development.

Next, check out the remaining historic sky bridges in New York City!

Subscribe to our newsletter