Spring Photo Walk at The Green-Wood Cemetery

Capture striking photographs of the gorgeous grounds and statuary of The Green-Wood Cemetery with the expert guidance of photographer Bethany Jacobson!

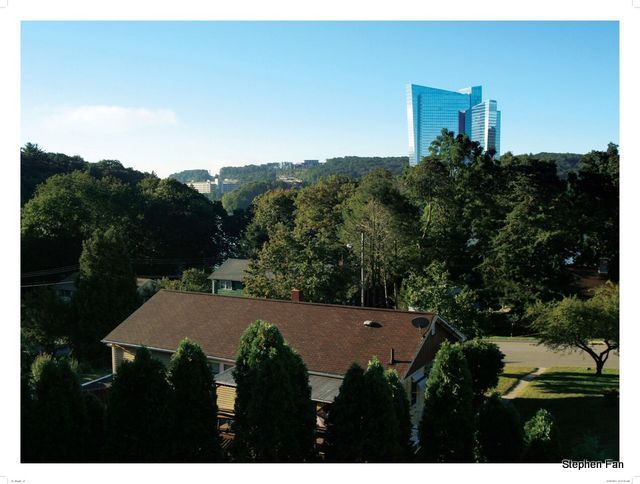

The Mohegan Sun casino rises behind suburban ranch houses in Connecticut

Every Saturday and Sunday, 40,000 staff and visitors pass through the tiny town of Montville, Connecticut, population 20,000. Their destination is the Mohegan reservation, home to one of the biggest Indian casinos in the country, Mohegan Sun. Through a couple quirks of history, a sizeable and growing portion of those staff and visitors are Chinese immigrants, and their presence in suburban Connecticut is the subject of a new exhibition at the Museum of Chinese in America: “SubUrbanisms: Casino Urbanization, Chinatowns, and the Contested American Landscape.”

The exhibition, which is up until January 31, was guest-curated by Stephen Fan, a designer and adjunct professor of architecture at Connecticut College, who has personal ties to the story – not only as a Chinese-American who grew up in southeastern Connecticut, but because his parents own the Golden Palace, a Chinese restaurant that has become the de facto gathering place for this particular immigrant community.

Floor plan of a typical ranch home, with Chinese additions and adaptations in red

Fan says the Chinese influx to the area came about under two circumstances. First, the Mohegan Sun underwent an ambitious expansion in the early 2000s, creating a staffing shortfall that couldn’t be readily filled by the local workforce. Concurrently, large numbers of Chinese immigrant workers in New York City lost work in the Lower Manhattan garment and restaurant industries following 9/11.

Of course, the housing stock awaiting these newcomers was neither sufficient nor familiar. So they adapted. The exhibition features three rooms demonstrating the different ways the Chinese dwellers repurposed and reinterpreted these prototypically American ranch-style homes, both increasing their occupancy and incorporating household norms and flourishes customary in their native China. A fourth gallery applies principles of these informal retrofits to a speculative design. Because so few own cars, and living rooms may be used as additional sleeping space, garages have been converted to common gathering areas, where the concrete floor provides a cool respite in the summer. Many have replaced front lawns with sprawling vegetable garden plots, and hang laundry and even fish out to dry, for all to see and smell.

Many Chinese replace front lawns with functional vegetable gardens

These visible signs of change, popping up suddenly around small Montville, provoked surprise and sometimes hostility among the town’s existing, mostly white population. The exhibition doesn’t shy away from addressing this culture clash, and uses it to try to instigate conversation about density, affordable housing, and micro-housing; what we consider urban vs. suburban in the West and in China; and the values, assumptions, and regulations that shape American suburban life. Most Americans live in suburbia, and may find the changes coming to Montville quite extraordinary.

The land under and around the Mohegan Sun was for decades marginalized and peripheral. The casino itself sits on the decommissioned United Nuclear Corporation facility which was designated a federal Superfund site, and its environs are dotted with cemeteries, a former psychiatric hospital and sanitorium, and homeless camps. A 240-acre reservation housing the casino/hotel/mall/convention center/arena, home to a WNBA team—and its attendant inflows of money, goods and people—was going to make sleepy Montville a little more bustling, Chinese workers or not.

Diagram showing bus routes connecting the Mohegan Sun to towns all over the Northeast. Credit: Stephen Fan and Shane Keaney

While some longstanding residents fear overcrowding in the Chinese-adapted homes, many inhabitants insist they are comfortable and abundantly practical. Since many of the workers are single, they share detached single-family homes with other singles and small families. Like a cooperative, they pool resources, share work tips and stories, and entertain each other. Housing is conceived as an adaptable infrastructure, rather than a consumer commodity to be used and sold when needs change. Homes designed with three bedrooms may house up to 12 people. But because the casino is a 24-hour operation, workers’ shifts are spread throughout the day and night, so the common areas in their homes aren’t necessarily overcrowded.

Since few Chinese workers drive, most walk, sometimes up to a half hour in each direction, to reach their jobs at the casino. Here is another way of life their American neighbors find baffling, though they say they enjoy the fresh air. Chinese commuters have trodden new pathways through cul-de-sac developments as shortcuts through neighborhoods that were not designed with the pedestrian in mind. Still, some are forced to walk along high-speed roads without sidewalks, a precarious condition that has resulted in at least two hit-and-runs. And in what Fan calls a “subtle form of spatial segregation,” some residents on these roads have put up barriers or signs that say “Do Not Walk on the Grass.”

Chinese workers, who walk to work rather than drive, have blazed new trails through suburban neighborhoods

Despite occasional gripes and tensions like this from longtime residents, the Chinese influx has helped invigorate an otherwise sagging local economy. One Chinese investor from New York City has bought up to a quarter of the properties in downtown Norwich, and is credited with helping turn around the town’s center. Local property values in the neighboring residential subdivisions are up, and with them, tax receipts.

When asked if any Chinese are really putting down roots in southeastern Connecticut, Fan says the same things that draw everyone else to the suburbs—clean air, a verdant landscape, and more space to raise a family—are what draw urban Chinese here as well. The only complaint they have is that “it’s kind of boring,” he says. “Though it’s a casino town, it’s not Vegas.”

Chinese-owned properties, shown in red, have helped invigorate a marginalized part of the state

“SubUrbanisms: Casino Urbanization, Chinatowns, and the Contested American Landscape” is on display through January 31 at the Museum of Chinese in America, 215 Centre St., Manhattan. A book of the same subject edited by Stephen Fan is also available on Amazon.

Subscribe to our newsletter