How to Make a Subway Map with John Tauranac

Hear from an author and map designer who has been creating maps of the NYC subway, officially and unofficially, for over forty years!

If you were to make a visit to the Museum of Biblical Art, what would you expect? I didn’t have a definite idea, more like half-formed visions of rosaries, painted wooden crosses, rosy Madonnas. The statue outside the Museum of Biblical Art in which it is housed didn’t do much to clue me in either.

A bronze statue of a man named Jeremiah Lanphier was seated on a bench, leaving space for others to join him. According to the brochure, Lanphier was simply a common businessman who started a prayer group in New York City in 1857. Initially composed of six people, the prayer group eventually consisted of thousands of members and sparked a citywide revival.

Located on the second floor, the pieces in the Museum of Biblical Art are housed in a spacious, warmly lit room. There was not a Renaissance mother and babe in sight. I decided it was time to look at the description to discover what I was missing. It seemed that I had come just in time for a new exhibit entitled Ashe to Amen: African Americans and Biblical Imagery. Ashe and Amen are words very frequently encountered in the African American religious community. Ashe, a Yoruba words, refers to a creative force, the power to make things be. Amen, widely used in Christian communities in general, means “so be it”.

Banned from reading, African-American slaves resorted to their own vibrant means of rebellion by expressing their spirituality and aspirations through art. This tradition of manifesting Biblical stories and messages through a distinct cultural eye is alive and well to this day, as you can see in the range of contemporary Biblical art exhibited in the Museum of Biblical Art. The first thing that drew my eye was what looked like a massive psychedelic swing woven from countless multicolored threads. I learned that this was a piece titled SISTAH PARADISE’S GREAT WALLS OF FIRE REVIVAL TENT: MYSTIC SEER *FAITH HEALER* ENCHANTRESS EXTRAORDINAIRE by Xenobia Bailey (1956-). Now there’s a name to match its regal appearance!

This tent, suspended from the ceiling, is supposed to symbolize a mystic gateway through which unsaved Africans are transported to the Promised Land, Africa. It features playful, decidedly feminine touches, most notably the teacup and floral patterns on its side, meant to parody place mats on dining tables. Xenobia Bailey is currently working on an Arts for Transit project that will be installed in the new 7 line 34th Street and 11th Avenue Station.

In an altar case with various small objects, I spot this brightly colored paint can lid is New Jerusalem by Sister Gertrude Morgan (1900-1980). A fascinating figure in her own right, Sister Gertrude was called to the “Headquarters of Sin,” New Orleans, at the age of 38. She preached in the streets with a tambourine and guitar and started an orphanage there with two other women. In 1957, God spoke to her again, calling her the “Bride of Christ”. In this artwork, she has depicted the fateful day on which Christ returns to claim her as his bride. Thereafter, she dressed herself and her furniture in white and painted matrimonial scenes such as this one. The angels around the periphery are the only witnesses of this fateful union.

Black Horse of Revelations

by Bessie Harvey (1929-1994). It is no surprise that Harvey, who left an abusive husband to raise 11 children herself and launch a successful career as an artist, should depict the Horseman as a Horsewoman instead, a tortured but strikingly powerful figure.

Made of roots and branches, the writhing, serpentine form of this sculpture indicates dynamic movement, as does the chain pulled taut in the rider’s grasp. The Museum of Biblical Art also features pieces that soothe as well as titillate in the Call and Response section, so named for a form of verbal and non-verbal communication devised by slave Christians for religious rituals. Resembling a shag rug, Glory #1 by LeRone Wilson (1969-) is actually made of a mixture of beeswax and resin.

For Wilson, the long-lasting nature of beeswax is a symbol of the everlasting love of Christ. How is that for inspiring?

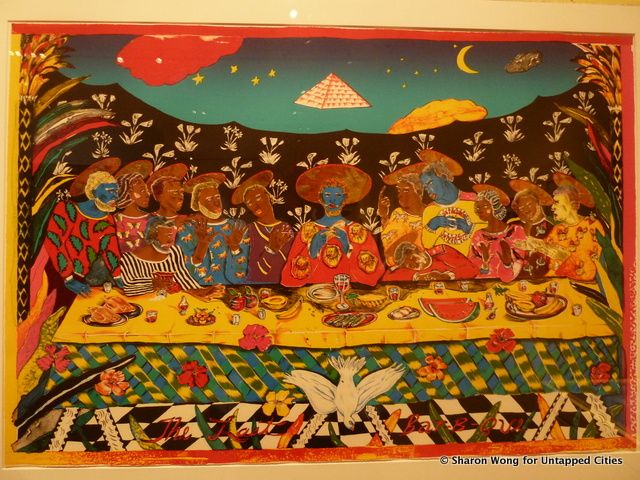

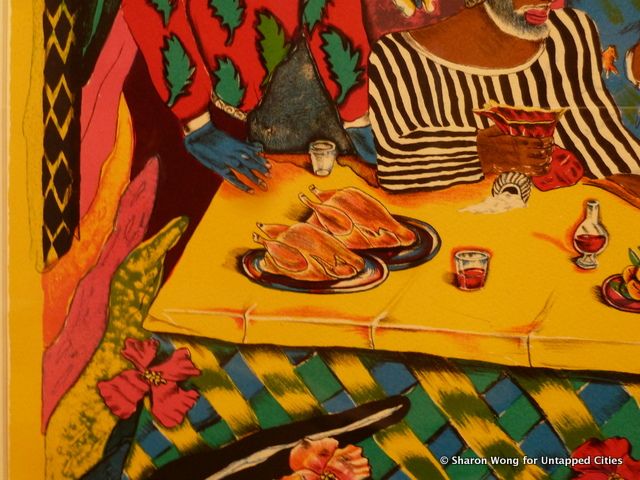

This beautiful lithograph, The Last Bar-B-Que by Margo Humphrey (1942-), is a highly unorthodox portrayal of the last supper. Not only are Christ and the disciples black, the meal itself includes soul food staples such as chicken and watermelon.

There were many other evocative pieces at the Museum of Biblical Art and sadly, some of the most beautiful of these did not come with stories. However, after my visit to the Museum of Biblical Art, I feel that my understanding of African American religious art has become nuanced, if not complete. One of the most marvelous things about this particular brand of Biblical art is that it can be lovely, frightening, awe-inspiring, comforting or completely zany all while maintaining a distinct, unified cultural and spiritual vision.

The Museum of Biblical Art’s exhibits constantly rotate, so stay tuned for the next one, As Subject and Object, exploring contemporary book artists’ interpretations of sacred Hebrew texts (June 14-September 29).

Subscribe to our newsletter