Minimalists Win the Great NYC Subway Map Debate, 50 Years Later

The NYC subway map has a new look that might look familiar...

Poor ventilation, tight quarters, nonexistent plumbing and seemingly endless filth was the reality of tenement housing complexes that dominated the 19th and early-20th centuries. Tenements provided a cheap, quick solution to the increasing amount of immigrants throughout New York City. Seeking the rumored economic opportunities in the United States, immigrants often fled famine, job shortages and rising taxes. Desperate to make a living and have a place to live, they piled into these hazardous buildings, making them even more filthy, less structurally sound and more prone to disaster. On Staten Island, the New Brighton Tenement collapse was one of the most disastrous of these building collapses in city history.

With the New York City population doubling every decade from 1800 to 1880, those in charge of building tenements often cut corners to complete their projects as fast as possible. Cheap materials and haphazard construction techniques left buildings vulnerable to destruction from natural disasters and daily wear and tear. With an average of 10 to 12 people per tenement apartment, overpopulation only weakened tenements further. By 1900, 2.3 million people resided in these narrow tenements within New York City.

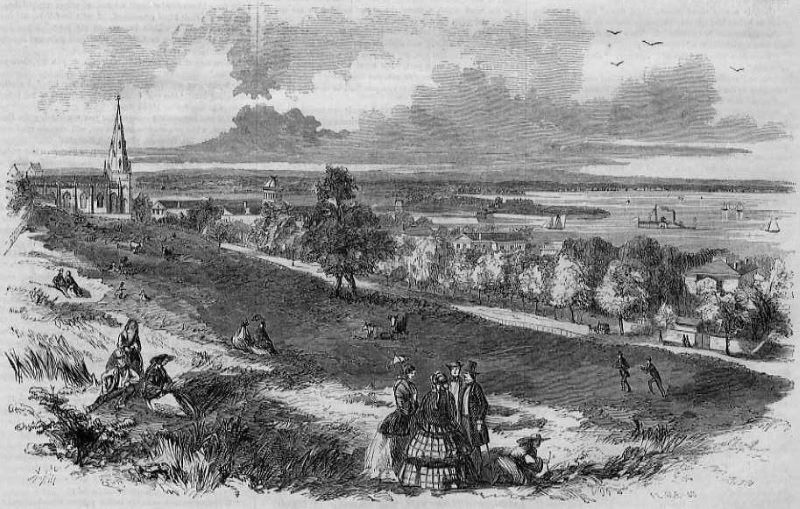

Although the Lower East Side hosted the most tenements in New York, Staten Island built some of its own. Few in number, Staten Island tenements often housed nearby factory workers who desired a home close to their place of employment. Free-standing single- or two-family homes dominated Staten Island during this time, though.

Tragedy struck a set of tenements on New Street in New Brighton, Staten Island — a neighborhood founded by industrialists and investors in the 19th century — during a stormy night on August 11, 1937. The three tenements — 1, 3, and 5 New Street — sat on a narrow cobblestone street surrounded by three hills. Whenever it rained, water would rush down the hill, flooding the street and often the basements of the buildings. Accustomed to wading through the water during storms, residents of the tenements simply proceeded with their normal evening activities. Many of these residents had little money to pay rent, while others paid $18 a month.

As water levels approached six feet outside the tenements, residents notified the police about the unusually high water levels. The policemen arrived at the scene to rescue residents from the flood. Preceding the collapse, those on the scene reported seeing the buildings sway. However, as residents called out for help, the buildings suddenly collapsed. The flood instantly washed the debris away.

“The houses just folded,” Bill Kovalesky, a locksmith at the scene, told the New York Times following the collapse. “They just slipped from under your eyes like magic.”

Estimated to be 40 to 50 years old, the tenements originally housed local textile workers. The victims of the New Brighton tenement collapse included immigrants, Staten Island natives and policemen on the scene. Moments after patrolman Joseph McBreen rescued two-year-old Patricia Hurley, the buildings collapsed. The following day, a search team found him with the girl’s arms wrapped tightly around his neck.

“A fine big man,” Police Commissioner Lewis J. Valentine told The New York Times following the collapse. “Lying there with his boots on. He must have suffered, lying there with his arms around that little girl. He had courage. Gratifying to have men like that in the department.”

When rescue efforts reached completion, the city declared that 19 people had died from the New Brighton tenement collapse. Four individuals, including William McGinn, the other patrolman at the scene, survived major injuries. Another survivor, 72-year-old John Mitchell lived in the tenement for 30 years before the police pulled him out from the ruins. Despite broken ribs, the doctors at Staten Island Hospital predicted he would recover.

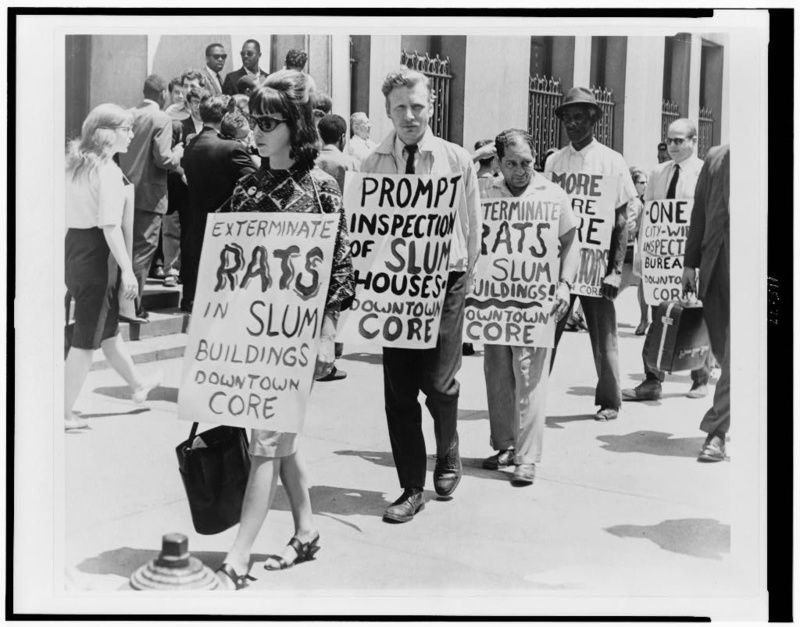

The New Brighton tenement collapse served as a wake-up call for some throughout the city. Lee E. Cooper, a real-estate editor of The New York Times, mentioned the collapse in his article about the Wagner-Steagall Housing Bill. When instated on September 1, 1937, the bill allowed the U.S. government to loan $500 million to low-cost housing projects. This reflected President Franklin D. Roosevelt‘s push for adequate housing for all. Senator Robert Wagner of New York championed the bill, making low-cost public housing for low-income Americans his priority. As the law required a new housing project to accompany the destruction of a building of substandard quality, living conditions in New York City slowly improved.

The Tenement House Act of 1901 prevented new tenement construction projects. However, it did not prevent disasters like the New Brighton tenement collapse from occurring. The work of activists like Jane Addams — founder of the Hull House in Chicago — and Jacob Riis — author of photojournalism publication “How the Other Half Lives” — along with pointed legislation led to the decline in tenement housing. Despite the tireless work of leaders and activists, many continue to live in homes resembling tenements. Better construction regulations, more frequent professional reserve studies and more adequate funds for repairs could prevent building collapses from happening in the future.

Next, check out the last wooden bridges on Staten Island!

Subscribe to our newsletter