Coffee Tasting Class & Roastery Tour at City Boy Coffee

Sample a diverse selection of coffees sourced from around the globe, then roasted right here in New York City!

Untapped New York is excited to partner on an editorial collaboration with the Gotham Center for New York City History. In this series, we’ll share fascinating stories from the Gotham Center Blog archives. These scholarly articles will explore New York City history through a variety of lenses and cover topics that range from Dutch colonialism to modern art!

“The story of Americans participating in the burning of New York has been suppressed in all American histories from that day to this.”[1]

—William Henry Shelton, 1929

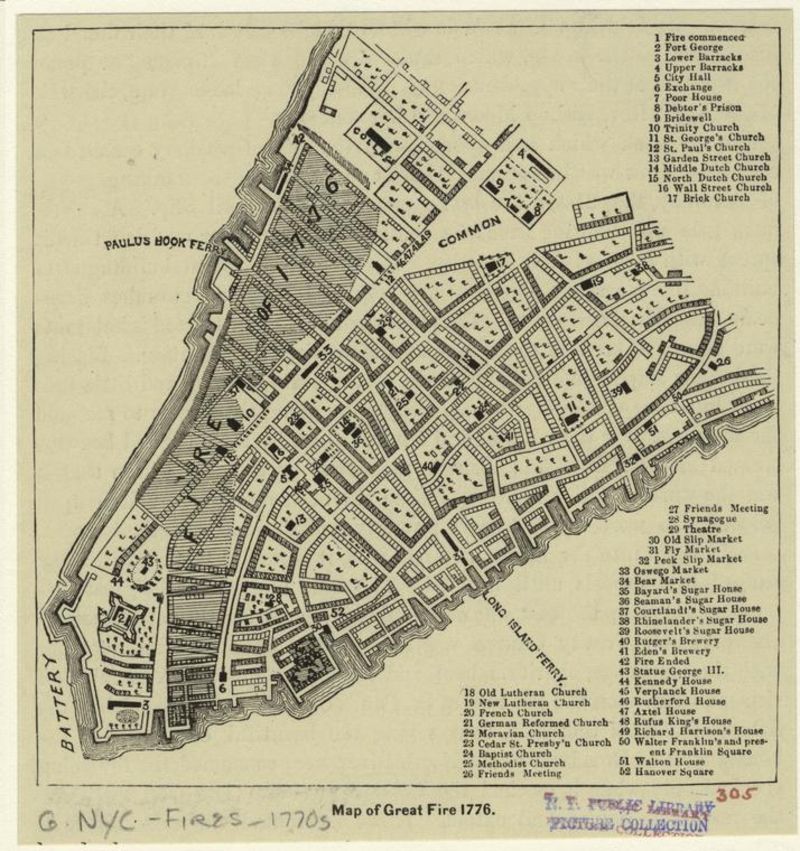

On September 21, 1776, a fifth of New York City burned to the ground, right before the British soldiers’ eyes.

But for almost 250 years, most New York City historians either ignored the Great Fire of 1776 or argued for its unimportance. They assumed that the fire was caused either by accident or by apolitical miscreants, and they chose to diminish the reports of outraged eyewitnesses who believed the fire was deliberate. The firefighter John Baltus Dash, for instance, testified that the fire broke out in two places at once, far too soon for the wind to have communicated flaming brands from one place to the other. He also found fire buckets with their handles cut and saw British soldiers arrest several people who had concealed combustible materials under their clothes. British officers and their Loyalist allies reported these facts and other evidence through their channels of news and intelligence, arguing that the Rebels — including General George Washington himself — were incendiaries who had perpetrated a villainous and atrocious act.[2]

But most Americans never heard this story, then or since, because intelligence reports from Washington, the Continental Congress, and Rebel newspapers suppressed any suggestion that Rebels might have burned New York City; they called it an accident or suggested that the British soldiers themselves had done the job. John Sloss Hobart, for instance, a member of the New York Provincial Congress, wrote that British soldiers, “having been promised the plunder of the town in case of conquest, . . . have set fire to the town in order to facilitate their views.” To deflect blame for the fire, Hobart reported, General William Howe’s soldiers threw suspected incendiaries into the flames or slit their throats.[3] American historians, relying on these rebel accounts, played down the story of the Great Fire or turned it into a British atrocity.

Americans were, in other words, encouraged to remember the Great Fire in a certain way. They developed a myth of American exceptionalism and tried to make New York City’s experience as a British garrison fit within that myth. Among New Yorkers, the memory of the Great Fire in the 19th century and beyond owed a great deal to a German-born tavernkeeper and merchant named David Grim. Grim lived in New York City as a Loyalist throughout the British occupation and he almost certainly knew Dash and other men who fought the fire. Grim died in 1826, but his reminiscences were discovered by the banker-historian John Fanning Watson during a visit to New York in 1828. From there, Grim’s tale became a staple: it propagated, through paraphrase and repeated reprintings, in at least twenty historical works over the course of the 19th century. Plenty of other histories ignored the fire entirely. The myth of an accidental fire took hold and became entrenched.[4]

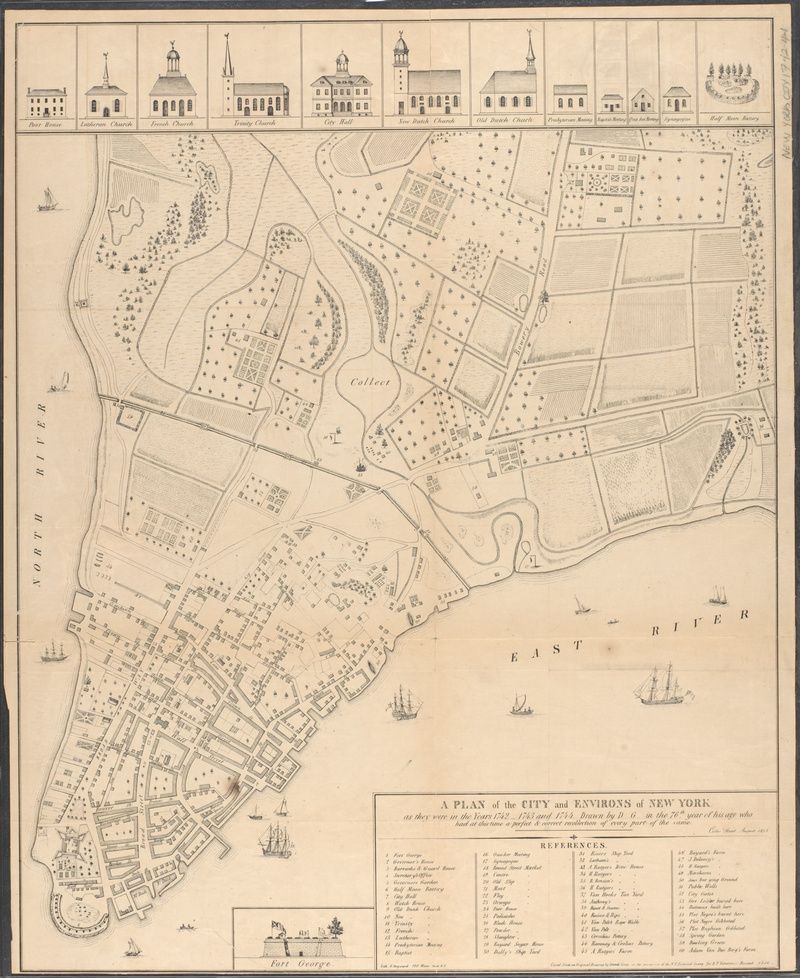

Grim’s remembrance never said outright that the fire was an accident, but unlike Dash’s testimony, it gave the fire a single point of origin — a Whitehall Slip tavern, which “was then occupied by a number of men and women, of a bad character.” (This titillating detail certainly intrigued the 19th-century audiences.) The reminiscence also described the fire’s subsequent wind-borne progress. Grim’s map — which has been reprinted and adapted repeatedly — shows the destroyed portion of the city as a contiguous area, with no indication of the suspicious combustibles that New Yorkers found elsewhere in the city. The map implies that the flames spread naturally, with no assistance from incendiaries (unless he meant that the “men and women of a bad character” were the incendiaries themselves). Grim gave the unusually precise figure of 493 houses destroyed. This figure was lower than most contemporary estimates, which minimized the fire’s effect. He also hinted that the British troops arrested many a “suspicious person,” but then released most of them; he made the troops sound quick to judge but devoid of proof. Finally, he did not mention any of the incendiaries whom the British executed: he only mentioned one victim, Wright White, as an unfortunate Loyalist in his cups whose erratic behavior got him killed (which contemporary sources corroborated). Grim diminished the credibility of the troops and the Loyalist eyewitnesses, who — in their reports — universally accused the Rebels of having set the fire.[5]

Watson used Grim’s account to exonerate the Americans from the British accusation that Washington’s men had committed an act of incendiarism. The Great Fire of 1776, he wrote, “excited a fear at the time, that the ‘American Rebels’ had purposed to oust them, by their own sacrifices, like another Moscow. It is however believed to have occurred solely from accident.”[6]

Watson — and the many historians who followed him — characterized Grim as a fellow antiquarian who helpfully shared maps and sketches of the city’s bygone days. Over the course of the 19th century, as Gotham’s population swelled to over a million people, audiences yearned for a local past that would serve its future. New York was slow, compared to many other states, in developing its local history. Since the city had been a British garrison town for almost the entirety of the war, it fit awkwardly into a national story, and local historians seemed reluctant to sully the city’s reputation. For them, David Grim was a useful vehicle for banalizing the Great Fire of 1776. Since Loyalists believed that the Rebels had deliberately set the fire, Grim appeared to be going against the grain. Still, Grim’s Loyalism was not fixed throughout his life; he may have revised his opinions as his allegiance shifted to the new United States.[7]

Indeed, Grim had good reasons to adhere to whatever flag New York was flying, since he had actively shaped New York City’s political and economic growth for decades. He electioneered for the DeLancey faction (who favored imperial trade and mostly became Loyalists) in the 1760s and celebrated the Stamp Act’s repeal in 1774 and 1775. During the occupation of 1776–1783, he sold dry goods, served drinks to Hessian soldiers, and managed lotteries for Loyalist charities.[8]

Then, after the war’s end, he became a merchant and prominent patron in federal New York. He was active in Federalist politics and belonged to the Society for the Relief of Distressed Prisoners and the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. He was a treasurer of the Lutheran Church (which had lost its building in the great Fire — Grim rented the ruin as a storehouse) and became president of the German Society in 1795. Grim held leadership positions in the Chamber of Commerce and the Mutual Assurance Company. He helped manage and owned shares in the Tontine Coffee House, a precursor to the New York Stock Exchange, and was president of the short-lived Bread Company, a monopolistic effort to break a bakers’ strike (until its building burned down). He did his best to accumulate wealth and uphold stability in the new republic, and his personal estate was assessed at $5000 in 1815 and 1820, putting him toward the bottom of the city’s wealthiest 1%. He claimed ownership of an enslaved person in early federal censuses; when he drew up his will in 1825, he bequeathed ten shares of Mutual Insurance Company stock, three shares of Bank of New York stock, five houses, and thousands of dollars in cash. In other words, Grim was underwriting the city’s economic future. His political sentiments had been British but became American. His understanding of the Great Fire may well have changed accordingly.[9]

Grim’s transition from Loyalist drinkseller to city father was not without setbacks. As the war ended, Grim’s brother Peter became a Loyalist exile and moved to New Brunswick, while David traveled to the mineral spas at Wiesbaden in western Germany, supposedly to relieve his rheumatism but possibly because New York’s political climate had become uncomfortable for him. Upon his return, a city official accused him of being a Loyalist refugee like his brother, and Grim had to bribe the man to stay in New York’s good graces. In February 1785, none other than John Sloss Hobart (now a state supreme court judge) threatened him with property seizure if he didn’t repay his debts.[10]

Grim’s shipping operations grew from there, but when the New York Chamber of Commerce passed a resolve in favor of the Jay Treaty in July 1795, “A REPUBLICAN” took to the Argus newspaper to attack the meeting’s attendees for their continued attachment to King George III. Most of them, “A Republican” acidly pointed out, weren’t “real Americans,” but were in fact “inimical to this country in the late war” or recent immigrants. The writer knew that David Grim (among others) had “resided within the British lines during the whole war.” The next day the Argus issued a correction, having learned that Grim was absent from the July meeting. Grim must have been shaken by the implication that his citizenship was contingent on his political beliefs. And so he left, as part of his legacy, an account of the Great Fire that was closer to Hobart’s propaganda than Dash’s testimony. Was it the truth, or was it Grim’s way of leaving his Loyalist past behind him? Had Grim spun a fairy tale?[11]

For all his apparent precision and his inherent value as a longtime resident of the city, Grim is not an ideal historical source. Although he was probably still in the city when the fire broke out, we do not know this for sure. His recollections did not appear in print until after his death in 1826. His statement about the fire’s origins at a Whitehall Slip tavern resembles a previously published (and stridently pro-American) history by the Reverend William Gordon, an Englishman who held a pulpit in Roxbury, Massachusetts, from 1770 to 1785. Gordon believed the reports of multiple outbreaks were “erroneous,” and instead — like Hobart — accused frolicking British sailors of having set the fire. It had become a badge of patriotism to deny that Rebels had deliberately burned New York City — Americans much preferred the idea that they had fought a righteous war and that their enemies were responsible for most of the atrocities.[12]

Grim might have been corroborating Gordon, or he might have been patriotically affirming the pro-American version of the fire’s story. From 1776 to 1783, Grim had been a Loyalist civilian living in a British garrison and then became a willing American citizen. He literally invested in the city’s future, its international trade, and the possibility of commercial relations with Great Britain. We know what he thought about the fire at the end of his life — but during the war, did he agree with eyewitnesses that the fire appeared to be deliberate? Why, if so, did Grim change his tune? Was it out of a desire for reconciliation between Loyalists and Patriots, between Britain and the United States? As the historian Donald F. Johnson writes, “civilians who had lived under military rule became adept at hiding or explaining away their wartime actions,” and in turn, “their neighbors and leaders proved willing to forgive their actions in the interest of forging a new American nationalism.” As Americans overlooked Grim’s Loyalist past, Grim became more willing to accede to Americans’ interpretation of the Great Fire. Although this is speculation, Grim’s status as a reintegrated Loyalist ought to affect our interpretation of his reminiscence.[13]

Grim presents a challenge to historians trying to get at the truth of the Great Fire of 1776. They should weigh his words against dozens of contemporary accounts from other Loyalists, British army and navy officers, and more distant Patriot eyewitnesses. In the ensuing centuries, scholars dismissed and discounted these sources due to their perceived bias or hysteria. These scholars concluded that Grim (and sometimes only Grim) was objective enough to be credible. “Old David Grim” was — at first — a convenient resource for historians of New York who were looking for the remains of the lost city that crunched beneath their feet. The city had been a British garrison town for seven years, and they wanted to conscript it into a more patriotic narrative. As historians repeated Grim’s story, the accumulated weight of those repetitions became so massive that it became difficult for later scholars to avoid their gravitational pull. We may never know with absolute certainty that the Great Fire was an accident, but Grim certainly made it harder for anyone to argue otherwise.[14]

Benjamin L. Carp is Daniel M. Lyons Professor of American History at Brooklyn College and teaches at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. His most recent book, The Great Fire of 1776: A Lost Story of the American Revolution (Yale University Press), tells the story of this devastating conflagration.

Sources

[1] William Henry Shelton, “Nathan Hale Execution and the New York Fire,” New York Times (Sept. 22, 1929), XX13

[2] Minutes of a Commission to Investigate the Causes of the Fire in New York City, New York City Misc. MSS, New-York Historical Society 8–12. Dash was a fellow officer of the city’s German Independent militia company of Loyalists with Peter Grim (David Grim’s brother). New York Evening Post, Nov. 29, 1811; “New York Militia of 1776,” New York Genealogical and Biographical Record 2, 3 (July 1871): 156.

[3] John Sloss Hobart to New York Convention, Sept. 25, 1776, Journals of the Provincial Congress, Provincial Convention, Committee of Safety and Council of Safety of the State of New-York, 1775–1777 (Albany, N.Y., 1842), 2:222–23.

[4] “Appendix: containing Olden Time Researches and Reminiscences of New York City,” in John F. Watson, Annals of Philadelphia: Being a Collection of Memoirs, Anecdotes, & Incidents of the City and Its Inhabitants from The Days of the Pilgrim Founders…(Philadelphia and New York, 1830), 47, 56, esp. 57–58 [second pagination]; see also Deborah Dependahl Waters, “Philadelphia’s Boswell: John Fanning Watson,” PMHB 98, 1 (Jan. 1974): [3–52] 12 n10, 21, 25, 26; William Dunlap, History of New Netherlands, Province of New York, and State of New York, to the Adoption of the Federal Constitution, 2 vols. (New York, 1840), 2:78–79; George Bancroft, History of the United States from the Discovery of the American Continent (Boston, 1866), 9:129; D. T. Valentine, “The Great Fires in New York City in 1776 and 1778,” Manual of the Corporation of the City of New York for 1866 (New York, 1866), 766–68; Martha J. Lamb, History of the City of New York: Its Origin, Rise and Progress (New York and Chicago, 1880), 2:135–36.

[5] Valentine, “Great Fires,” 766 (“bad character”), 767 (“suspicions persons”).

[6] Watson, Annals, 57 [2nd pagination].

[7] Mercantile Library Association, New York City during the American Revolution (New York: Mercantile Library Association, 1861), 126 n7; Philander D. Chase, “Grim, David (1737–1826), tavern keeper, merchant, and antiquarian,” American National Biography, Feb. 1, 2000 (Accessed 22 May. 2020) (“antiquarian”); an engraving of David Grim’s map showing the extent of the fire, by George Hayward, was widely reproduced after its initial publication in Valentine, “Great Fires” (1866), opp. p. 766. See also Clifton Hood, “An Unusable Past: Urban Elites, New York City’s Evacuation Day, and the Transformations of Memory Culture,” Journal of Social History 37, 4 (summer 2004): 883–913. On “formulas of banalization,” see Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (Boston: Beacon, 1995), esp. pp. 26, 83, 96 (quote), 97, 102–7, 147–48.

[8] New-York Journal, April 12, 1770; New-York Gazette and the Weekly Mercury, March 21, 1774, Feb. 3, 1777, Feb. 7, 1780; Rivington’s New-York Gazetteer, March 23, 1775; “New York Loyalists,” MLA, New York City during the American Revolution, 126; “Petition of 547 loyalists from New York City, November 28, 1776,” New-York Historical Society; Diaries of a Hessian Chaplain and the Chaplain’s Assistant, ed. and trans. Bruce E. Burgoyne (n.p: Johannes Schwalm Historical Association, 1990), 7, 16 n20; Chase, “Grim, David”; Christopher F. Minty, Unfriendly to Liberty: Loyalist Networks and the Coming of the American Revolution in New York City (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2023).

[9] New-York Journal, July 28, 1792, April 3, 1793; New-York Daily Gazette, April 3, 1793; Daily Advertiser (New York), April 9, 1792, Feb. 11, 1794, Nov. 9, 12, 1801; American Minerva (New York), March 5, 1794, Jan. 23, 1795, March 10, 1795; Herald (New York), June 8, 1796; Minerva (New York), Jan. 4, April 5, 1797; The Constitution of the New-York Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge and Piety (New York, 1794), 10; The Constitution and Nominations of the Subscribers to the Tontine Coffee-House (New York, 1796), 34, 39, 46; Walter Barrett [Joseph Alfred Scoville], The Old Merchants of New York City, 3rd ser. (New York, 1865), 10, 13, 224; The Knickerbocker Fire Insurance Company of New York, Originally the Mutual Assurance Company of the City of New York, 1787–1875 (New York, 1875) 44; Annual Report of the German Society of the City of New York (1883), 31; Stokes, Iconography (1915), 1:450; Howard B. Rock, “The Perils of Laissez-Faire: The Aftermath of the New York Bakers’ Strike of 1801,” Labor History 17, 3 (1976): 372–87; “Comparative Wealth of Citizens of New York, During and Subsequent to the last War with Great Britain,” in D. T. Valentine, Manual of the Corporation of the City of New York (New York, 1864), 758; 1790 and 1810 census, Ned Benton and Judy-Lynne Peters, eds., New York Slavery Records Index: Records of Enslaved Persons and Slave Holders in New York from 1525 though the Civil War (New York: John Jay College of Criminal Justice, 2017), https://nyslavery.commons.gc.cuny.edu/ (accessed June 2, 2020); New York Surrogate’s Court, Record of Wills, 1665–1916, vol. 60, 1825–26 (microfilm, Reproduction Systems for the Genealogical Society of Salt Lake City, 1971), roll 29, pp. 179–83.

[10] New-York Morning Post, Feb. 15, 1785; Chase, “Grim, David.”

[11] “A REPUBLICAN,” Argus (New York), Aug. 7, 1795; see also Argus, Aug. 8, 1795; New York Chamber of Commerce to George Washington, July 21, 1795, The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 18, 1 April–30 September 1795, ed. Carol S. Ebel (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2015), 386–388; Sarah J. Purcell, Sealed with Blood: War, Sacrifice, and Memory in Revolutionary America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002), chap. 3; Brett Palfreyman, “Peace Process: The Reintegration of the Loyalists in Post-Revolutionary America” (Ph.D. diss., Binghamton University, 2014).

[12] William Gordon, The History of the Rise, Progress, and Establishment, of the Independence of the United States of America: including an Account of the Late War…, 4 vols. (London, 1788), 2:330 (“erroneous”), 331.

[13] Donald F. Johnson, “Forgiving and Forgetting in Postrevolutionary America,” in Patrick Griffin, ed., Experiencing Empire: Power, People, and Revolution in Early America (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2017), 171–88, 172 (“civilians,” “neighbors”).. An advertisement in Constitutional Gazette (New York), Aug. 21, 1776, and New-York Gazette and the Weekly Mercury, Sept. 2, 1776; implies that Grim was still in the city a few weeks before the fire.

[14] Grant Thorburn, Sr., “Old Down Town Churches,” New-York Observer, Nov. 4, 1858 (“Old David Grim”).

Subscribe to our newsletter