Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

Dyckman. Stuyvesant. John Jay. They are some of the most recognizable names in New York City, gracing streets, parks, schools and neighborhoods. But they are also connected to slave owners. “New York was … certainly the major slaveholding state in the north,” said Kenneth T. Jackson, president emeritus of the New-York Historical Society, professor emeritus at Columbia University, and editor of The Encyclopedia of New York City. In the 1770s, the city’s population of 25,000 included approximately 7,000 black residents, the bulk of whom were slaves.

Some of these influential men changed their beliefs over the years, reducing the number of slaves they owned and eventually supporting the abolitionist movement — even though a few of them did so without actually freeing their own. And while New York legally ended slavery in 1827, 38 years before the 13th amendment abolished it in the United States, having ties to a place named for a slave owner is uncomfortable for modern-day New Yorkers — though some are already familiar with the namesake’s history.

“I’m aware that Peter Stuyvesant was hugely influential in our city and the expansion of our city — and he, like many other major figures, has an unpleasant part of his story as well,” said 33-year-old Stuyvesant High School alumna Eleonora Srugo, a Douglas Elliman real-estate agent, adding she learned about Stuyvesant’s slaveholding during a city history class as a student there. “So does the entire country, though.”

Here are prominent slave-owning New Yorkers and the places in New York City that bear their names:

Bust of Peter Stuyvesant located in St. Mark’s Church in the Bowery

Peter Stuyvesant “was an absolute jerk,” said Kenneth T. Jackson, “He didn’t like Lutherans, he didn’t like Catholics, and he didn’t like Quakers. This was not a nice person.” However, the director-general of New Netherland — the Dutch colony that included New Amsterdam, which later became New York City — made big historical strides: among them, establishing the first municipal government of New Amsterdam in 1653, and authorizing the construction of a market, a canal and a defense wall where Wall Street is today.

Traces of Stuyvesant are most visible around the East Village. That’s where he established his Bouwerie farms, from which the Bowery gets its name and where Stuyvesant Street still exists today. It’s also where he kept as many as 40 slaves to tend the land. That number likely made Stuyvesant, whose name is also attached to a leading city public high school and Manhattan’s largest apartment complex, one New Amsterdam’s biggest slaveholders.

During his time as director-general, slaves accounted for about 10 percent of New Amsterdam’s population, which was just under 10,000 inhabitants. Not only did Stuyvesant have his own slaves, he also enabled the sale of slaves in the settlement and may have overseen its first slave auction. Stuyvesant – who died around age 80 in 1672 and is memorialized with a statue in Stuyvesant Square Park at Second Avenue and Rutherford Place as well as at the St. Mark’s Church in the Bowery — also actively sought to prevent Jewish refugees from settling in New Amsterdam and referred to Quakers as an “abominable sect.”

Historians recognize John Jay, the country’s first chief justice, as a statesman who promoted the abolition of slavery while serving as governor of New York State. But not only did Jay, for whom the John Jay College of Criminal Justice is named, descend from a family of slave ship investors, he was also a slaveholder himself. Between 1771 and 1817, Jay owned at least 18 slaves total, according to the New York Slavery Records Index, a collection of records compiled by John Jay College researchers.

One slave, known only as Benoit, was purchased by Jay in Martinique for an unknown price in 1779 and freed in 1784. Another, Massey, escaped in 1778 to join the British Army. Jay’s wife, Sarah Livingston, came into the 1774 marriage owning her own slave, Abigail; she escaped in Paris while Jay negotiated the Treaty of Paris to end the American Revolution, and died in jail there. Jay claimed he owned slaves to free them: “I purchase slaves and manumit them at proper ages and then their faithful services shall have afforded a reasonable retribution,” he said.

Partial of John Jay’s portrait by Gilbert Stuart, located in the National Gallery of Art. Image in public domain from Wikimedia Commons.

Partial of John Jay’s portrait by Gilbert Stuart, located in the National Gallery of Art. Image in public domain from Wikimedia Commons.

Even as he kept owning slaves, in 1785, Jay co-founded the New York Manumission Society, which sought emancipation and to ban the general practice of slavery. Three years later, the society enacted a law that barred the removal of slaves from New York to be sold in other states. And in 1799, four years into his term as governor, Jay signed an act for gradual abolition into law, which eventually freed the children born to slaves after that date, but indentured them until their mid- to late- 20s — a compromise in a legislature largely made up of slaveholders. (Another law passed in 1817 guaranteed gradual freedom for slaves born before 1799 in 1827.)

“You can see a family moving from being slavers to being abolitionists, and John Jay sort of at the pivot point,” said professor Ned Benton, who works on the slavery index, with colleague, professor Judy Lynne Peters, adding, “There’s also a function of the time because people were beginning to say, ‘This doesn’t feel too good.’ He was in a position to do something about it.” A statue of John Jay was erected inside John Jay College in 2014 in celebration of the school’s 50th anniversary.

Portrait of Dewitt Clinton by Rembrandt Peale. Image in public domain, from Wikimedia Commons.

DeWitt Clinton’s name graces a popular 5.8-acre park, a NYCHA development and a high school. All despite the fact that the former New York City mayor and New York State governor, who masterminded the Erie Canal waterway linking the Hudson River to the Great Lakes, owned slaves. In fact, he came from a family of slave owners — including his uncle, long-serving governor George Clinton — who are the namesakes for Brooklyn’s Clinton Hill neighborhood.

For his part, George — a founding member of the Manumission Society, which promoted abolition — owned as many as eight slaves, according to the 1790 census. DeWitt’s upstate-based father, James Clinton, owned up to 13, according to those same census records.

Dewitt Clinton Park

“Anyone in New York State in particular who owned more than 10 individuals is … in a league all their own,” said Brooklyn Historical Society historian Nalleli Guillen. “Holding enslaved people became a marker of affluence and prestige.” DeWitt, as far as records show, owned at least two slaves while living in New York City: a woman named Massa, whom he freed in 1810, and another named Jenny.

Despite George’s position with the Manumission Society, he wasn’t as active an advocate for abolition as figures like John Jay, said Guillen. DeWitt, meanwhile, signed deeds freeing slaves during his years as mayor and supported public education, an avenue that allowed free black children to attend school. By the time of his death in 1858, he owned no slaves. “They both … existed within this sphere, but it doesn’t sound like they were particularly vocal on [abolition],” said Guillen. “It doesn’t seem like they did a whole lot of heavy lifting.”

The Dyckman Farmhouse in Upper Manhattan

For Meredith Horsford, executive director of the Dyckman Farmhouse Museum, researching the history of slavery at this uptown property dovetails with the Black Lives Matter movement. “We’re saying the same thing about the enslaved: Say their name,” she said. With a grant from the New York Community Trust, researchers have uncovered details of the slaves owned by the Dyckmans, for whom Dyckman Street, which cuts across Manhattan uptown and continues into The Bronx, is named. The family amassed and farmed 250 acres of land in what’s now Inwood. To tend to all the property, they owned as many as 15 slaves.

Census records between 1800 and 1830 show that Jacob Dyckman, whose great-grandfather Jan originally settled in Harlem in the late 1600s, owned as many as 15 slaves. The 1840 census, meanwhile, shows that his son Isaac owned 10 in an apparent inheritance. Francis Cudjoe, whom Jacob Dyckman freed in 1809, is the only slave known by his full name.

Extended family slaves included individuals named Will, Gilbert, Harey and Blossum. Meanwhile, a free black woman named Hannah lived with the family and worked as a cook. In records, she’s described as having “a … face black as ebony, temper decidedly irregular, and a strong leaning towards a corncob pipe.”

Inside the Dyckman Farmhouse where a 2019 exhibition called attention to the history of slaves at this site

“We believe that they slept in a sleeping loft [of the farmhouse], which was probably an open space,” said Horsford. “It probably would have been extremely hot in the summer and in the winter, I would imagine that someone would have to stay awake throughout the night to feed the fire and keep the house warm.”

Her goal is to infuse this research throughout the entirety of the museum’s curriculum for visitors to understand every aspect of the farm. So far, the museum has hosted a virtual lecture series on race. This month, local artists will install site-specific works to show the slave history. “Talking about that story is just as important as talking about the Dyckmans,” said Horsford. In May, Untapped New York hosted a virtual talk with Horsford discussing the history of slavery in the Dyckman family. You can see a video of the talk in our members-only video archive.

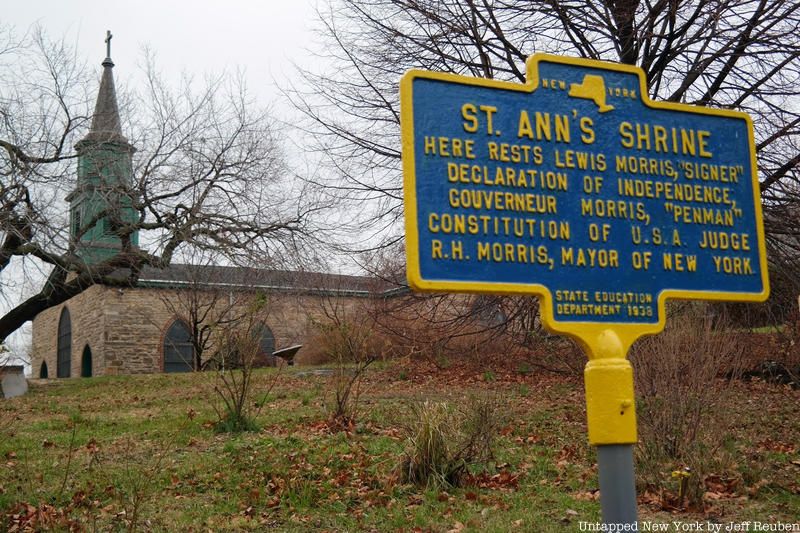

The Morrisania neighborhood in The Bronx is known as a birthplace of hip-hop: where Grandmaster Flash hosted neighborhood parties and groups like the Cold Crush Brothers got their start in local after-hours clubs. It’s named for the colonial manor of the Morris family, an influential clan of politicians — including Lewis, who signed the Declaration of Independence, and his brother Gouverneur, one of the framers of the Constitution; and their grandfather, also named Lewis, who was chief justice of New York. The manor spanned thousands of acres across the southwest Bronx and was worked by as many as 30 slaves at a time, according to Bronx Borough Historian Lloyd Ultan.

“When they were working in the house … they would be doing things like washing the dishes, cooking and doing the laundry,” said Ultan of the slaves, adding they also helped the women dress and cared for the children. “In the field, they were not only raising the crops, some of them actually became craftsmen in a sense,” adding they made barrels to transport wheat to Manhattan by boat to sell on behalf of the family.

The former Morrisania Hospital

The family apparently brought slaves with them from the Caribbean, where they had sugar plantations. Subsequent Morris generations owned fewer slaves; according to the 1810 census, Gouverneur owned two. “At that time, they saw a contradiction between the ownership of slaves and [the] ‘all men are created equal’ [philosophy],” said Ultan. “What happened is that eventually both of them got rid of all their slaves.”

New York City had a complicated status during the Civil War as well, when many prominent leaders supported the Confederacy due to business ties in the South — well documented in the book City of Sedition. The city was also a stronghold of support for Abraham Lincoln and the Union war effort. The narrative of New York City has always been full of contradictions, which have left marks on the physical urban fabric.

[post_featured_tour]

Next, check out 10 stops on the Underground Railroad in NYC.

Subscribe to our newsletter