Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

Structures built for World’s Fairs are usually built to be taken down. This happened with nearly every building from the 1939 World’s Fair, including the Trylon and Perisphere, and most of the buildings from the 1964 Fair. While many of the major pavilions were deconstructed (and sometimes shipped to other places), there are still remnants of the Fairs that exist today. These vestiges of the fairs have since become iconic landmarks of New York City such as the Parachute Jump in Coney Island, the Unisphere in Flushing Meadow-Corona Park in Queens, and the Queens Museum. Another World’s Fair remnant that it is hard to picture New York City without is the New York State Pavilion. Once the 1964-65 Fair wrapped, however, the future of the Pavilion was uncertain.

Currently the subject of a massive restoration project, the New York State Pavilion was once under threat of demolition. People for the Pavilion co-founder Salmaan Khan has been fascinated by the Pavilion since he was a child. The non-profit organization is “devoted to raising awareness of the historic value of the New York State Pavilion, and of its potential to serve as a vibrant and functional public space.” Curious to know if the structures were meant to be permanent, if there was a plan for them after the fair, and if there was a reason for their abandonment, Khan began searching for answers at the Rockefeller Archive Center. What he found were numerous correspondences between important New York City officials who were instrumental in determining the pavilion’s fate.

The New York State Pavilion, designed by Philip Johnson, was made up of three observation towers known as the Astro-View Towers, the Tent of Tomorrow, and the Theaterama. In January 1964 a letter to New York City Councilman Seymour Boyers, Robert Moses spells out preliminary plans for some of the Fair structures. The post-fair park had been on his mind since the first World’s Fair at the site in 1939.

While Moses didn’t specifically mention the New York State Pavilion in his initial letter, he did after note that “…most of the Fair buildings are temporary, are built on poor foundations, must be removed and, in any event, are completely unsuited for any post-Fair use.” In response, Nelson Rockefeller’s Lieutenant Governor Malcolm Wilson made his desire to save the Pavilion known. After all, it was paid for with taxpayer money as he notes:

Moses was especially interested in saving the Astro-View Towers, but it wasn’t solely his decision to make. A report by the New York City Department of Parks staff presented a few problems that threatened the future use of the Pavilion. The report noted that the Towers wouldn’t meet City codes for use as an observation deck, but could remain as ornamental structures, along with the Tent of Tomorrow and the theater. Moses vehemently disputed this point in his response to the report, arguing that there was no evidence to support the staff’s claim. Moses was passionate about preserving the “terrific” view from the towers. In the following letter to Parks Commissioner Newbold Morris, Moses says “there is nothing else like it in this part of the City.”

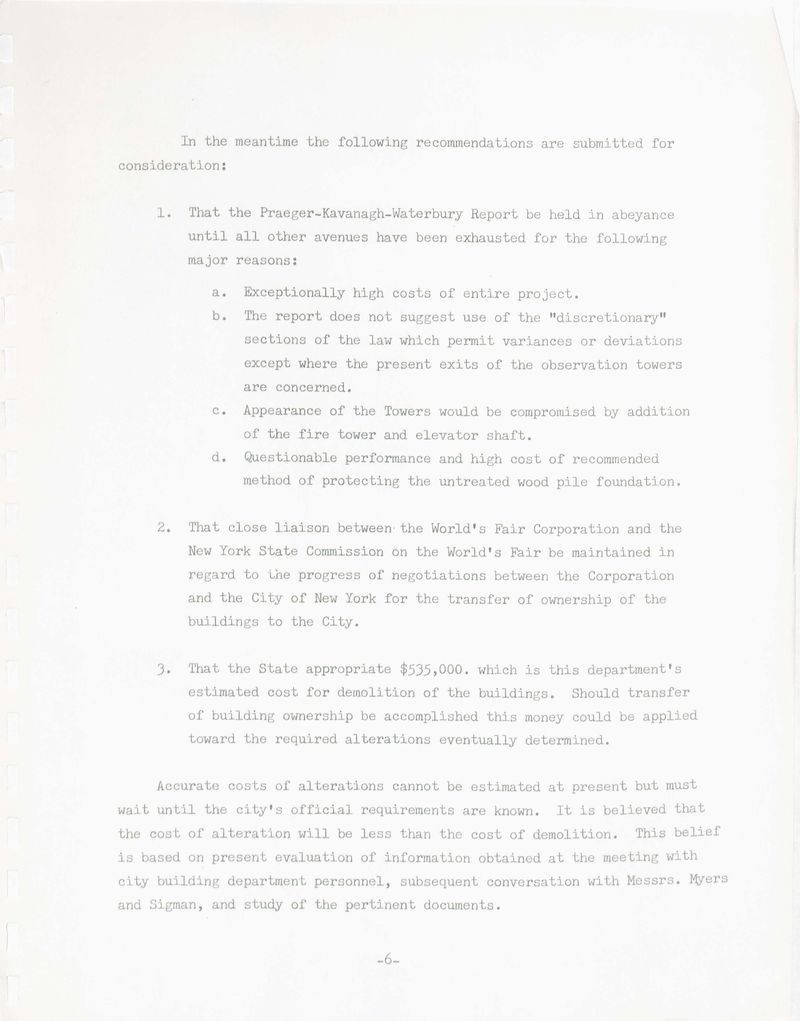

It was the hope of Moses and the Governor’s office that the Pavilion could be preserved and ownership of it transferred to the City of New York. In January 1965, a report was published by the State of New York Department of Public Works that broke down the cost of such a plan. A previous report had estimated that it would cost $1.3 million to bring the structures up to City codes. They were built under lenient code restrictions for the fair. Demolition on the other hand would only cost $750,000. The State put forward several ways to help minimize renovation costs.

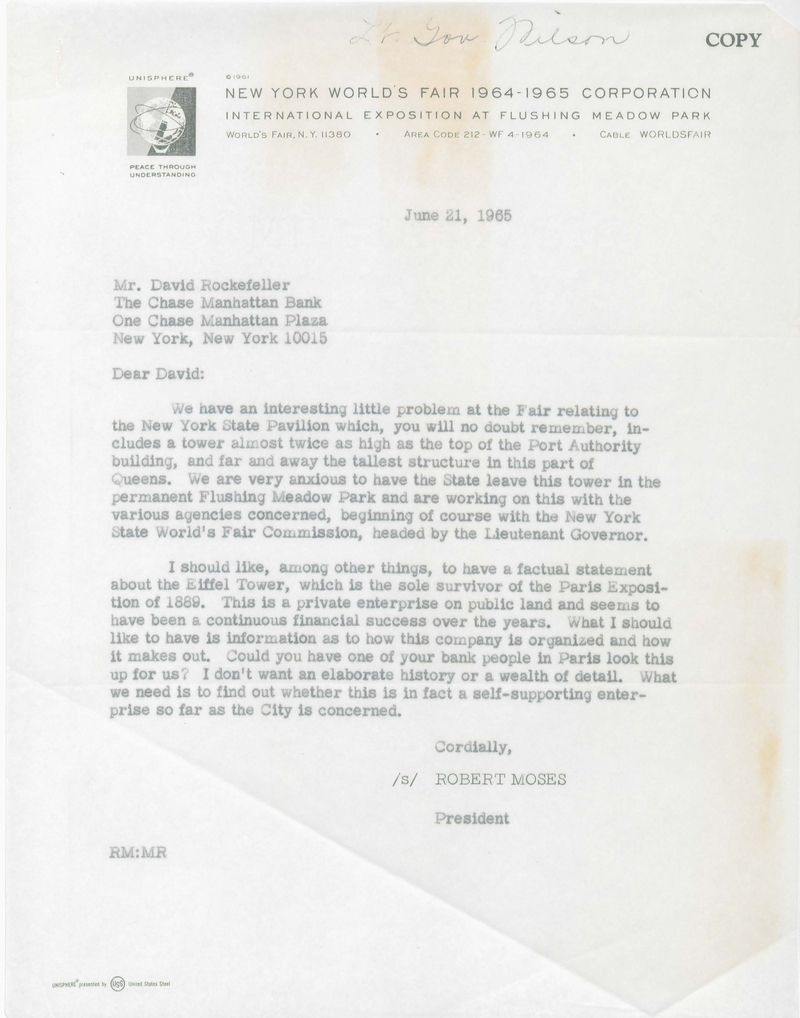

In a bid to help bolster his case in support of preserving the Towers as observation decks, Moses reached out to David Rockefeller for information about the Eiffel Tower, a survivor of the 1889 Paris Exposition. In the letter below, Moses asks Rockefeller to check with his French connections to see if they could gather any information on how the Eiffel tower, a private enterprise on public land, became financially stable, in hopes that the same could be done with the Towers in Flushing.

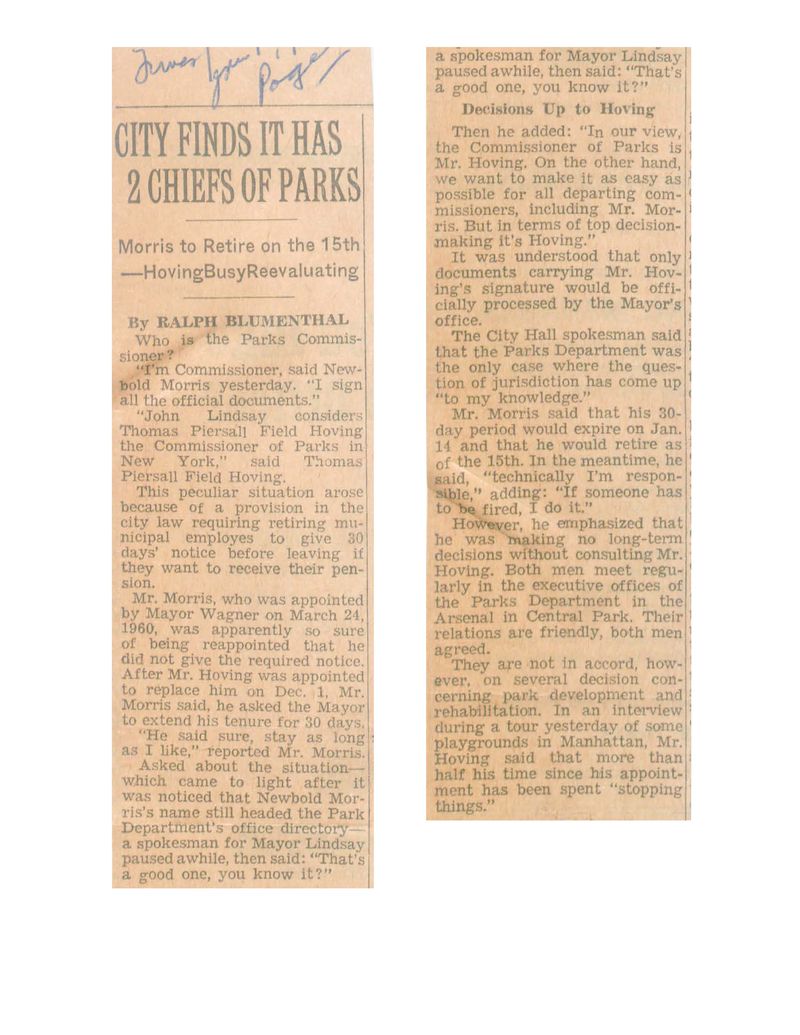

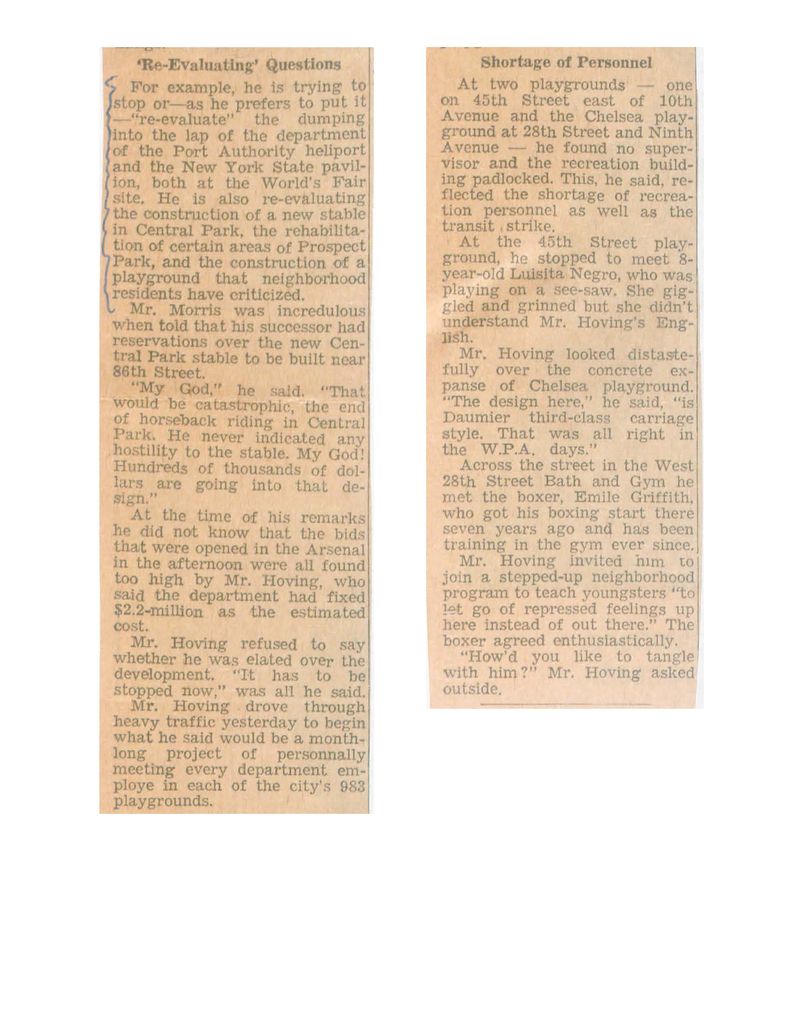

The quest to preserve the Pavilion hit another snag in early January 1966, when New York City found itself with two Parks commissioners. Newbold Morris and Thomas Hoving simultaneously held the position when Morris, expecting to be re-appointed, failed to put in a 30-day notice of resignation. Instead of keeping Morris on the job, however, Mayor Lindsay appointed Hoving to be the new commissioner. The two commissioners had opposing views on what to do with the Pavilion. Hoving wanted to “re-evaluate” the City’s acquisition of the Pavilion. He preferred the more economical plan of demolishing it. When The Top of the Fair restaurant inside the heliport building closed, a structure formerly owned by the Port Authority then transferred to the City, Hoving’s resolve was only bolstered.

Despite Hoving’s desire to give up on the fair buildings, Governor Rockefeller, Luitenant Governor Wilson, Robert Moses, and others wanted them to stay. In the middle of January 1966, the State comptroller awarded the City $750,00 to help cover the costs of bringing the buildings up to the appropriate City codes, the same amount it would have cost to demolish the buildings. After this victory, there was still much work to be done.

The buildings wouldn’t be transferred to the City of New York until April 1968. After the fair, the Tent of Tomorrow became a concert venue where acts like The Byrds, Fleetwood Mac, Santana, and the Grateful Dead performed. It also served briefly as a roller skate rink before closing in the 1970s. The Theaterama is now home to the Queens Theater. The Observation Towers never did become the attraction that Moses dreamed they could be, but they are part of the current restoration project which is estimated to be finished by the end of 2023.

You can dive deeper into the campaign to save the New York State Pavilion and see more primary documents on the People for the Pavilion website here and see these structures firsthand on our upcoming tour of the remnants of the World’s Fair in Flushing Meadows-Corona Park!

Next, check out 10 Secrets of Flushing Meadows Corona Park and Locate Remnants of the Aquacade from the 1939 World’s Fair

Subscribe to our newsletter