Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

The Polo Grounds is a strange name for a baseball park, yet baseball is what was played at New York’s Polo Grounds. It is the ancestral home of the Giants, one of baseball’s oldest and most venerated teams. In fact, it has the distinction of being the home at one time of four of New York’s major league baseball teams, all except the Dodgers, who played in Brooklyn. The Polo Grounds existed at three locations in Manhattan and five iterations before the final version was unceremoniously demolished in 1965, eight years after the Giants decamped to San Francisco.

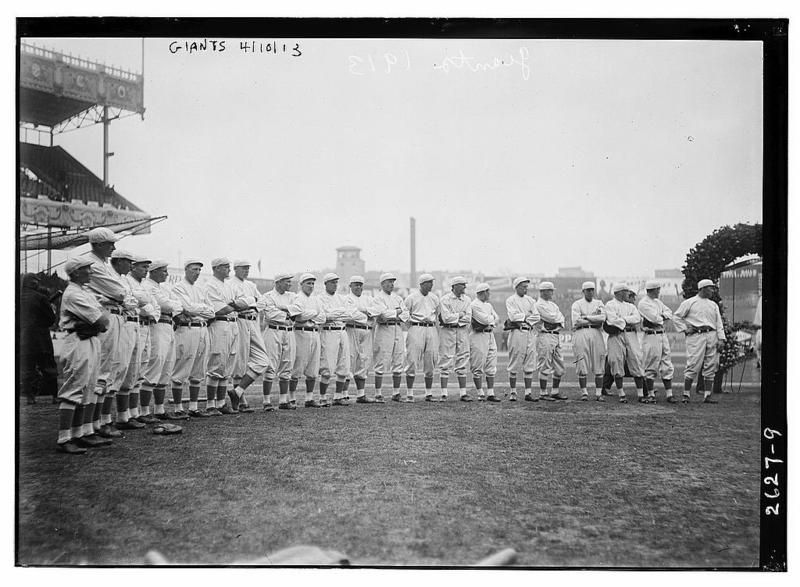

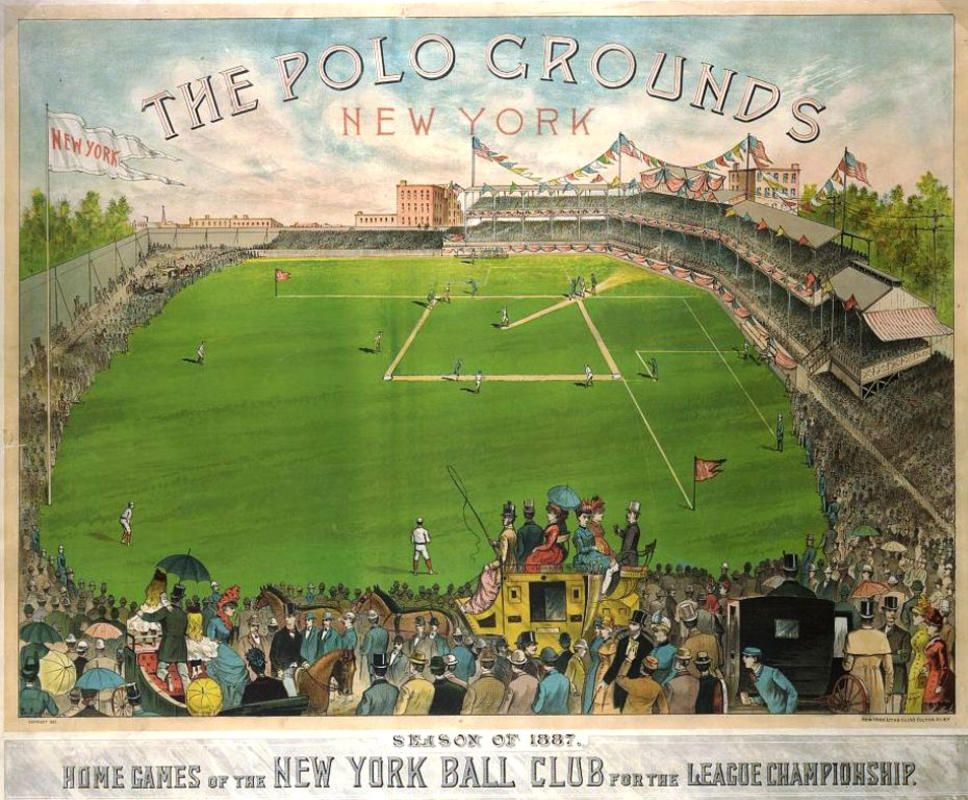

Baseball sprouted up seemingly out of nowhere in a national craze after the Civil War. New York’s first professional team, the Nationals, was formed in 1883, but they were known as the Giants by 1885. They made their home at the original Polo Grounds, a tiny grandstand on a field between Fifth and Lenox Avenues, between 110th and 112th Streets, just north of the recently completed Central Park (1876). Polo was played there; hence, the odd name. The original Polo Grounds was the site of the Giants’ first championship in 1888, the beginning of a long, good run as one of baseball’s best teams.

During their 75 years in New York, the Giants won 17 National League (NL) league championships and eight world championships, three before the advent of the modern World Series in 1903. They sent more players to the Hall of Fame than any other during this period. Long before Babe Ruth came to the Yankees in 1920 and before the Yankees won their first World Series in 1923, the Giants were firmly established as New York’s favorite and most beloved baseball team. Yet somehow the luster of the Giants’ golden years in New York has faded. One reason for this is the Yankees’ enduring dominance (40 pennants and 27 World Series victories). The other is the never-ending nostalgia for the thoroughly inferior but beloved Dodgers, the Lords of Flatbush (12 pennants in 74 years in New York but just one World Series title, in 1955).

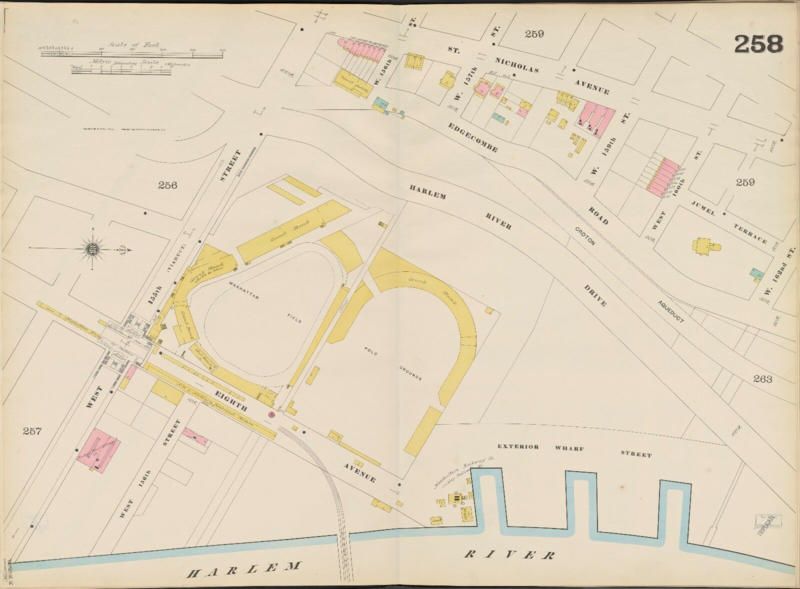

This glorious run by the Giants did not take place on their Fifth Avenue field, however. In 1889, the Giants were forced to move because the City wished to complete the street grid through the Polo Grounds. After a frantic search, the team settled further uptown, on a new playing field hastily built on a meadow called Manhattan Field situated along the Harlem River near 155th Street, below the Coogan’s Bluff escarpment. This remote site was feasible because it had good public transportation links. The then steam powered Ninth Avenue Elevated, New York’s first elevated railroad (opening in stages beginning in 1871), went directly to the site, via Eighth Avenue above 110th Street. The New York and Northern Railroad, later the New York Central’s Putnam line, was another option, extending from its 155th Street terminal to the Bronx and north into Westchester and beyond. Later, the City’s amazing IND Subway line (1932) would supplant the El in providing service to the Polo Grounds.

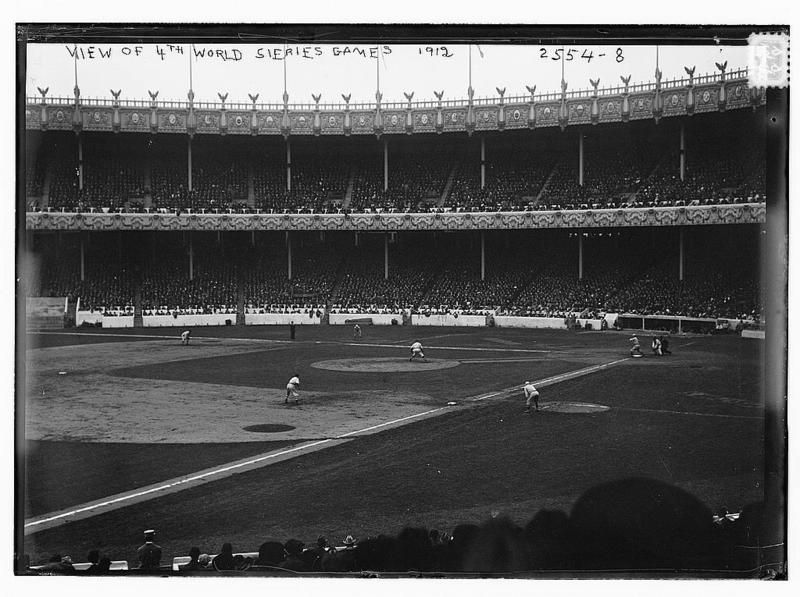

Somehow, the Polo Grounds name followed the team when it moved. A relatively modest two-story wooden grandstand was built in 1889 at the Manhattan Field site, at which the Giants promptly won their second championship. In 1891, the Giants made a short move into a larger ballpark on the adjacent lot at 157th Street. A striking feature of this third version of the Polo Grounds was that it was open in the outfield. This was not unusual in the so-called “dead ball” era of the game, when home runs were infrequently hit, so spectators could watch the game from the playing field, as seen in this fabulous panoramic photo from the 1905 World Series (which the Giants won).

When the team moved to this site, it foolishly declined an offer from the powerful Gardiner family that had owned the property since colonial days that would have enabled the team to acquire the entire meadow below Coogan’s Bluff. Instead, they took a narrow lot with just enough land to accommodate the original modest grandstand. This blunder would curse the Giants with an oddly shaped ballpark for the rest of their many years in New York and ultimately contribute to their departure.

The picturesque grandstand built on the third site was destroyed by a mysterious fire early in the 1911 season. The team relocated to the nearby but far inferior Hilltop Park used by their new American League (AL) counterpart, the Highlanders, located on Broadway near 165th Street.

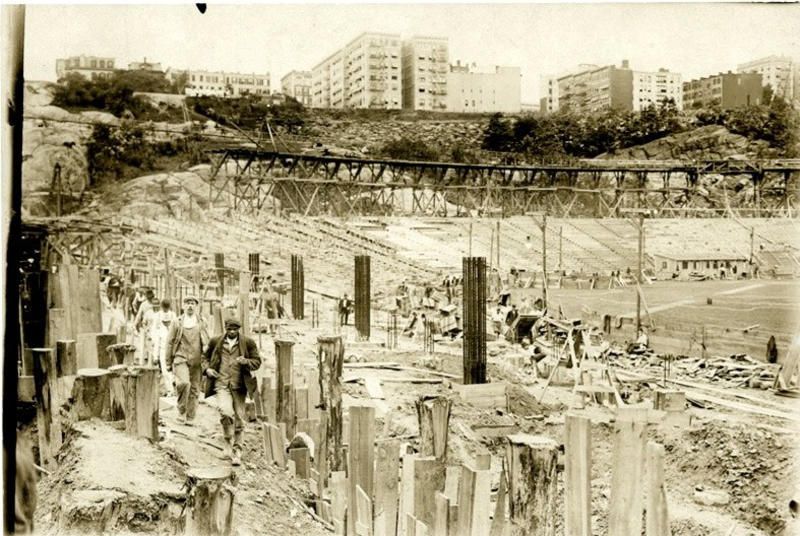

A new grandstand was rapidly built and the Giants returned home later that year. The new grandstand was made of steel and was delightful, complete with decorative friezes and sculptures of eagles (from the NL’s logo) perched on the roof. It was much larger too, but because of the narrow lot lines of the property, it had a horseshoe shape playing field, with short distances down the foul lines and an enormous expanse of territory in centerfield. The ballpark was expanded and remodeled dramatically in 1923, which resulted in the unfortunate destruction of the friezes and the disappearance of the eagles. The Giants were left with an ungainly structure and a strangely configured field.

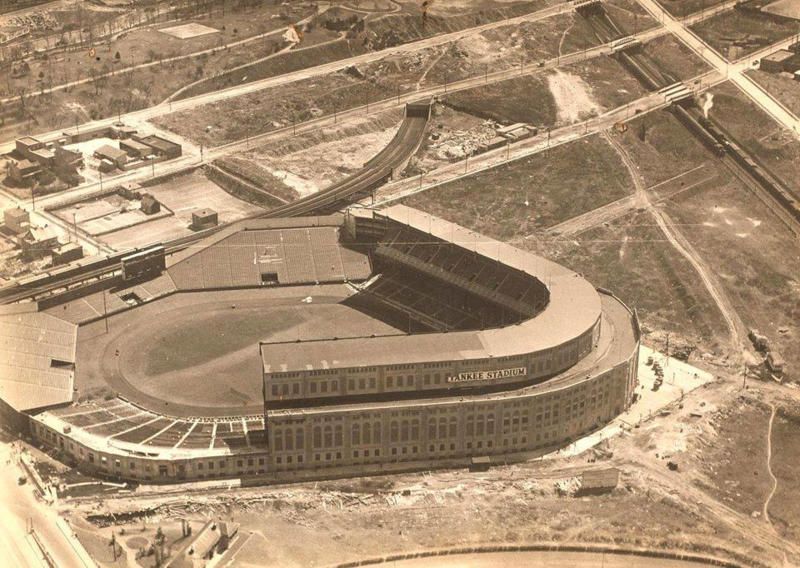

The Polo Grounds was America’s premier sporting venue at least until 1923, when the Yankees (the renamed Highlanders) opened Yankee Stadium directly across the Harlem River in the Bronx. Before then, the Yankees shared the Polo Grounds with the Giants for ten seasons, including the first three years of Babe Ruth’s legendary career as a Yankee. In 1921 and 1922, the Yankees and Giants played each other in the World Series, with all the games played at the Polo Grounds (the Giants won both). The following year, the Yankees exacted revenge, defeating the Giants in the first of the many World Series that would be played at Yankee Stadium.

Some of the most prominent events in baseball history occurred at the Polo Grounds. Renowned manager John McGraw ran the club from 1902 to 1932, accumulating 2,669 wins, still the most in NL history. His teams featured many stars, such as Christy Mathewson, an adored pitcher who won 373 games, an NL record that will never be broken, and who was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1933 as one of its original five inductees, alongside Ruth. The 1934 All-Star Game, held at the Polo Grounds, is remembered for the performance of Carl Hubbell, who struck out five of the game’s best hitters—Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Jimmie Foxx, Al Simmons and Joe Cronin—in succession. In 1951, the Polo Grounds was where the Giants’ Bobby Thomson hit the “Shot Heard ‘Round the World,” the playoff home run that defeated the Dodgers and won the pennant, capping an extraordinary comeback known as the Miracle of Coogan’s Bluff (the Giants lost the World Series to the Yankees that year however). In the 1954 World Series, Willie Mays of the Giants, who for a time lived in Harlem on nearby St. Nicholas Place, made “The Catch,” snagging a blast from Vic Wertz of Cleveland while streaking out into the immense centerfield at the Polo Grounds, the signature moment of the Giants’ final World Series victory in New York. The Polo Grounds was also an important site for Negro League baseball games played by the New York Cubans during that league’s golden era, 1935-1950. The Negro League held its 1947 All-Star game at the Polo Grounds, drawing 42,000 fans.

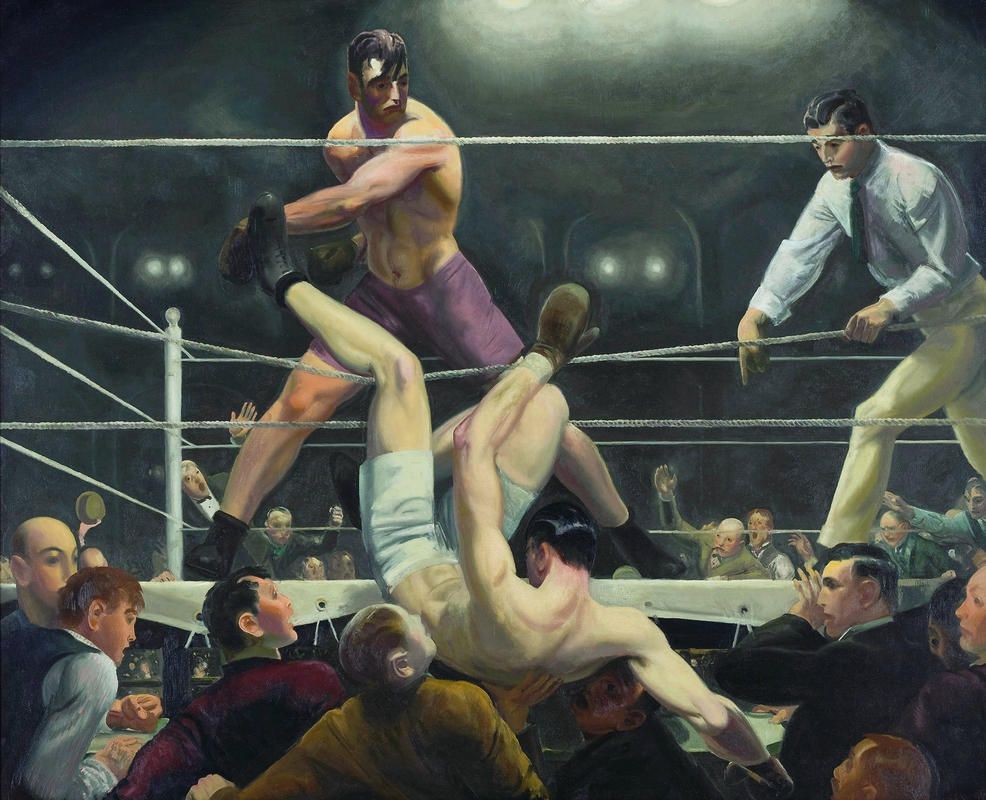

The Polo Grounds’ fame extended well beyond baseball. It hosted many championship boxing matches, including two of the most famous. In September 1923, 80,000 spectators witnessed champion Jack Dempsey fight Argentine Luis Firpo, the “Bull of the Pampas,” during which Firpo knocked Dempsey out of the ring, a moment in sports history immortalized in a painting by George Bellows. Dempsey ultimately prevailed. The Polo Grounds also hosted the classic 1941 bout between long-time heavyweight champion Joe Louis and the tough middleweight Billy Conn. A tiring Louis, behind on points by all counts late in the fight, came back and knocked out Conn as the middleweight imprudently went for the KO in the 13th round.

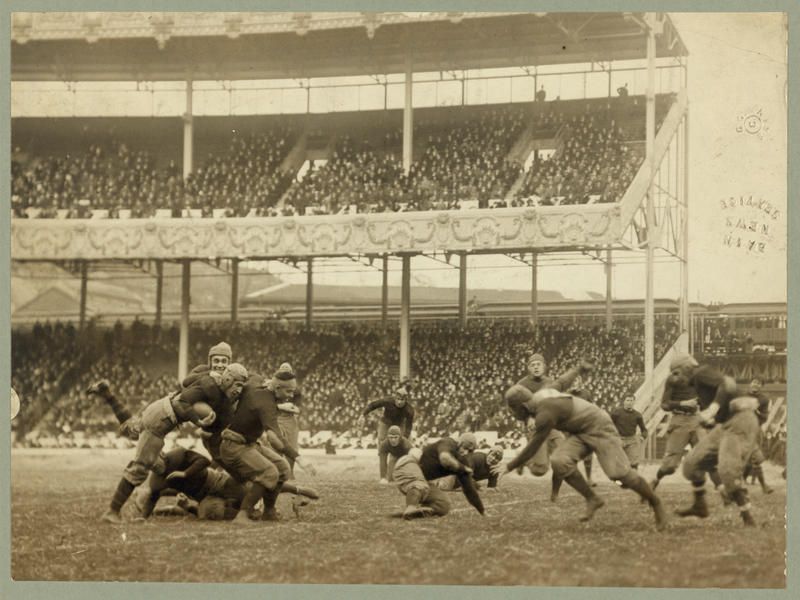

The Polo Grounds also was a premier venue for professional and college football for decades, hosting hundreds of games. It was the home field for Fordham and Columbia and hosted many traditional Ivy League rivals, as well as the revered Army-Navy game nine times. The Polo Grounds was home turf for the New York Giants football team (referred to as the “Football Giants” by the newspapers for clarity) from 1925-1955 and later, the New York Jets (originally the Titans), for their initial three seasons, 1962-1964, in the upstart AFL before its merger with the NFL in 1966.

Despite all this, and the success of the Giants on the baseball field, the old ballpark by the 1950s had seen better days. Attendance fell as the post-war boom began to draw people out of the city and transportation by automobile became dominant. The Polo Grounds, hemmed in by Coogan’s Bluff and the Harlem River, was not well-sited for expansion or redevelopment in this new era. The construction of large public housing project adjacent to the ballpark did not help matters for the team. In 1957, finding no government support for a new ballpark, the Giants announced they would move to San Francisco the following year along with the Dodgers, who were moving to Los Angeles. The Giants played their last game at the Polo Grounds on September 29, 1957.

But baseball was not over at the Polo Grounds. In 1962, New York was awarded a new NL franchise, the Mets, to replace the two they lost. While a new ballpark was being built in Queens (Shea Stadium, named for a power broker lawyer instrumental in bringing the new team to New York), the Mets played their first two seasons at the Polo Grounds, which was repainted, resodded, and updated with better lighting. The final MLB game at the Polo Grounds was on September 18, 1963.

But even that was not the end of professional baseball in Manhattan. There was one more notable game to be played, which has been largely overlooked. On October 12, 1963, the first and only “Latino All-Star Game” was played at the Polo Grounds. First-generation Latino baseball legends filled the lineup card, including Giants’ star pitcher Juan Marichal and their slugger Orlando Cepeda. The Pirates’ electrifying Roberto Clemente played and managed one of the teams. Thus, the final baseball game at the Polo Grounds can also be seen as marking the beginning of a new era in professional baseball dominated by Latino players. A fitting farewell to a fine old ballpark.

Next, check out 8 of NYC”s Lost Baseball Stadiums

Subscribe to our newsletter