Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

We kick off a new series about the late NYC architect Richard Roth Jr., starting with his debut design, Tower East!

Over the years, my Dad, architect Richard Roth Jr. would make off-handed comments about how he should write a book. He was always a storyteller and had many fascinating anecdotes that only an “insider” would know. He was in the room when things happened.

My Great-grandfather, architect Emery Roth, founder of the prolific architecture firm my father would eventually inherit, Emery Roth & Sons, wrote an autobiography that is now in the Avery Library at Columbia University. Titled Autographical Notes 1940-1947, it was typewritten and bound into two volumes with handwritten scribbles and edits.

In 1960, my Grandfather Richard Roth Sr., published a book titled ‘Your Future in Architecture.’ I do not know how many copies were published or sold, but I have two. Every once in a while you can find one for sale online.

When my Father moved to Florida I was constantly after him to put his own stories down on paper, to record them, to do something. There were many failed attempts. He complained it was too hard to type, so I suggested dictation. He didn’t like that. I suggested getting someone to dictate to, but he rejected that. He did claim he started writing some of the stories down on his laptop but he “lost” them (similar to “the dog ate my homework”).

After he died in 2022, I found four of his laptops and searched. Nothing came up except a few opening chapters he did write. Those chapters covered little more than his childhood memories of living at 210 West 101st and then the penthouse apartment designed by Emery Roth. The text ended prematurely with his acceptance to architecture school. Sadly there was nothing about the many buildings he worked on and designed in his forty-year career.

During COVID-19, I finally convinced him to do interviews and virtual talks with Untapped New York. I also got him on a podcast with the Pan Am Museum and other outlets. Before that, he had done one recorded interview in 2019 with architectural historian Annie Alt, a retired early childhood educator who immersed herself in the architectural history of New York City.

It was during one of Untapped New York’s virtual talks that I flippantly wrote in the comments, “Who would like to write the book on my dad?.” Jo Holmes responded, “I will take a stab at it” with a winky face emoji.

The three of us—me, my Dad, and Jo—began a series of Zoom discussions. With those discussions, the Untapped New York interviews, and assorted writings and notes I had found, Jo started to craft a series of essays. Sadly my Dad passed before the series was complete, but Jo has continued the project, for which I am forever grateful. I am also grateful for Justin Rivers and his conversations with my Dad. Those interviews help to keep his stories alive. You can watch them in the Untapped New York video archive.

Every month this year Untapped New York will release a new essay from Jo Holmes’ series on my Father’s life and work. Each essay explores a different building or developer from Richard’s career, intertwined with stories of his personal life, education, travels, and love of art. The series will be accompanied by talks and tours through which we will visit Roth buildings in person or virtually. The first event will be a live-streamed tour and talk on March 12th. I hope you’ll join us!

—Robyn Roth-Moise

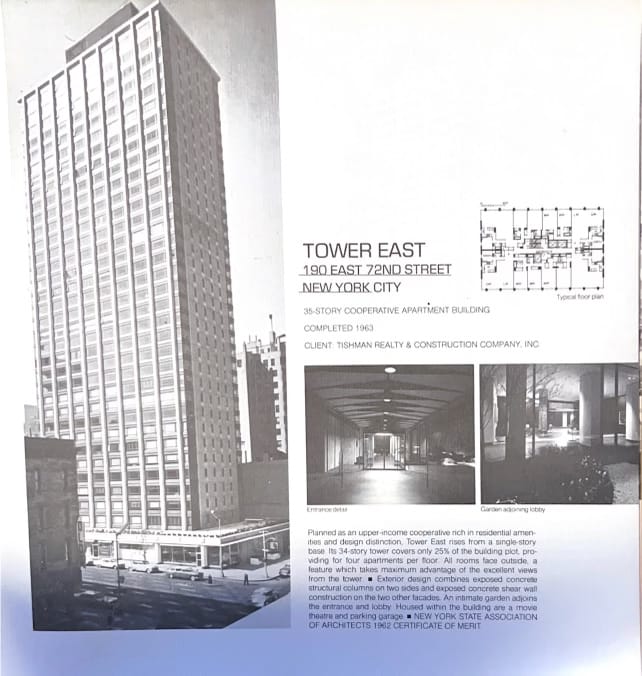

Richard Roth Jr.’s career as an architect began to take off in the 1960s. His favorite building from those early days was Tower East on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. The 34-story tower is on the southwest corner of 72nd Street and 3rd Avenue and comprises 130 luxury apartments with plenty of light. Completed in 1960, the building is notable for a number of New York firsts in terms of the materials and the structure. It was also the first time Richard worked independently of his father, who had been a strong influence and support.

Richard joined the family architecture firm of Emery Roth & Sons in 1957 after graduating from Miami University of Ohio. He started off as a junior draftsman. For some time, all his work was carried out under the watchful eye of his father, Richard Roth Sr., but Tower East was the first project where Richard Sr. gave Richard Jr. free rein. Richard worked closely with the client, Peter Tishman, who was emerging from under his own father’s wing. Leading New York realtor Norman Tishman and Richard Roth Sr. were old friends. They had similar misgivings about their sons’ ideas for the property but ultimately left them to it.

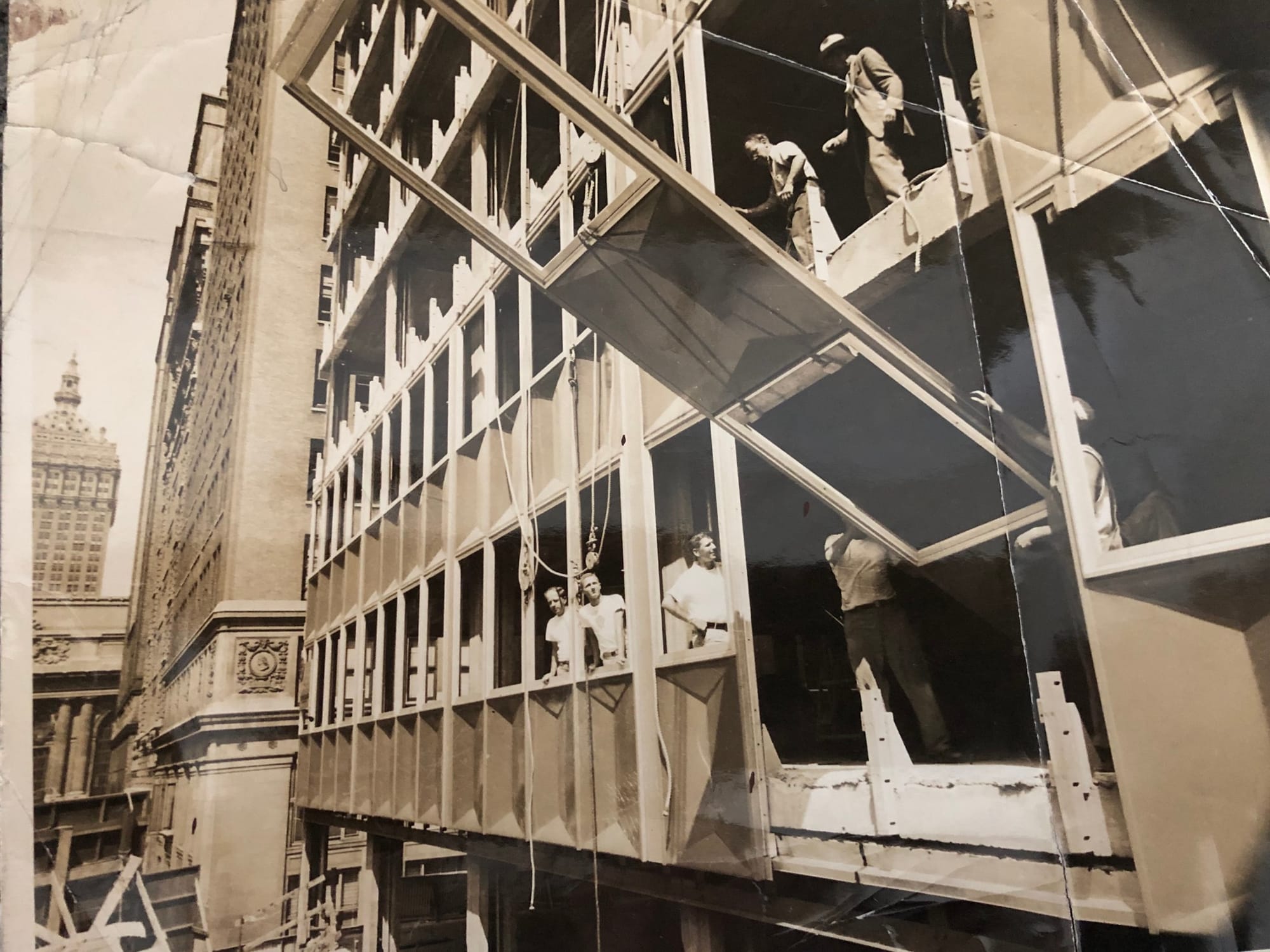

Richard wanted to do something that hadn’t been done in Manhattan before. “One of my gods in the world of architecture was Corbusier,” said Richard. “He used cast-in-place concrete and showed it. And that’s what I wanted to do, so I designed my building with cast-in-place concrete.” Up until then, this was unheard of in the city: I. M. Pei’s exposed concrete Kips Bay Towers were built around the same time as Tower East. New York concrete masons had to quickly learn that their product could be more than just a building material but had an aesthetic quality as well.

Richard says his design was also inspired by another trailblazer of modernist architecture: Mies van der Rohe. He had pioneered the curtain wall—a feature Richard employed on Tower East. The glass corners of Tower East are reminiscent of the Bauhaus School building itself and the Fagus Factory, both in Germany and designed by Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius. Richard would later work with Gropius on the infamous Pan Am Building (now known as the Metlife Building) in Manhattan.

Richard and Peter decided to use a brand new product from major metals producer Alcoa. “They brought Duranodic aluminum to show us. It was a beautiful brown color. And we used it to create the curtain wall,” explained Richard. Tower East was the first apartment house with a curtain wall in New York. Within a few years, the aluminum turned grey. “We were kind of guinea pigs for the product, which Alcoa subsequently improved. But even to this day, I think the greyness in the Duranodic adds to the look of the building. So, I was not that unhappy,” added Richard.

As noted in New York 1960: Architecture and Urbanism Between the Second World War and the Bicentennial by Robert A. M. Stern, Thomas Mellins, and David Fishman, Richard and Peter decided against balconies—but for different reasons. Richard didn’t think people would enjoy the views over Third Avenue enough to want a balcony. Peter thought people would enjoy the view better with windows unobstructed by balcony surrounds.

A first that can’t be attributed to Tower East relates to New York City zoning regulations. “People think it was the first building built according to the new regulations that came in in 1961,” says Richard. “In fact, it was the last building built under the old rules that had been in place since 1916.” Under those rules, you could build a building any height as long as the floor area was less than 25 percent of the size of the plot (and you’d need to include setbacks above a certain height). To achieve the floor space Richard wanted, the Tishmans ended up buying the neighboring plot. That allowed for spacious apartments—with plenty of closets, a trademark feature of Emery Roth & Sons designs, dating back to Richard’s grandfather’s day. The extra plot included a small one-story bank building with Greek columns. The building’s still there —attached to the apartment block by a canopy that surrounds the site and a garden area–looking perfectly integrated with the tower.

Another ‘last,’ indicating times were changing, is that Tower East is the last building Richard recalls including a designated maid’s room in the apartment design. A combination of new household appliances, ‘stay-pressed’ clothing, convenience foods, and cost pressures meant domestic service had dropped by half between 1940 and 1950 and the trend continued. By the 1970s domestic help had become a luxury, not a standard feature of middle-class life. Nowadays, those maid’s rooms in Tower East are marketed as extra bedrooms or home offices.

Despite the generous space in the apartments, Norman Tishman and Richard Roth Sr. were skeptical about the design. They believed it would make more sense to build something similar to the nearby brown brick apartment blocks. It must have been hard to ignore the older generation’s advice, given their long experience in the business. But Richard Jr. and Peter stuck to their guns and Richard was grateful that Peter enabled him to build his design.

He was also grateful for his father’s role in his life, though he perhaps lacked warmth. Richard said his father wasn’t affectionate: “He wasn’t a hugger,” but the letters he sent when he was based in the Solomon Islands during the war reveal a touching tenderness for his son. For example, in a letter to his wife in February 1943—when Richard Jr. was turning 10 years old, he signs off: ‘I love you and hope Richard had a swell birthday. I will be thinking of him on the twentieth —kiss him for me and let him kiss you for me.’

Perhaps the fact he wasn’t one to heap praise on anyone made his compliments more powerful and meaningful. Richard recalled his father telling him sometime in the 1970s that his office was better than his own had been: in other words that they were producing better designs. “That meant a lot,” he said. What’s more, Richard Jr. credits Richard Sr. with supporting him on several fronts, recognizing and understanding his talents and abilities. “He thought I should be an artist,” said Richard—not a career many parents would deem practical, profitable, or secure enough to pursue. At the same time, Richard Sr. sent Richard Jr. to work in construction during school and college vacations, which proved to be an invaluable experience once he became an architect. It was also Richard Sr. who encouraged his son to attend Miami University in Ohio, which had a profound effect on Richard’s life, both professionally and personally.

With a titan of architecture for a father, Richard Sr.’s own career was perhaps inevitable. It seems there had simply been an understanding he’d become an architect and join his father’s firm. That’s not to say he did everything his famous parent expected of him. On his return to New York after the war, Richard Sr challenged Emery’s design for an apartment building at 880 Fifth Avenue, persuading him the plans should be redrawn to preserve the firm’s reputation. In time, Richard Sr changed the image of the firm from focusing on masonry buildings to high-rise glass and steel towers. In 1926, he eloped because Emery didn’t approve of his fiancée Edith, Richard Jr.’s mother, who wasn’t Hungarian. “My grandfather must have come round as they did eventually have a celebration in their penthouse apartment on the Upper West Side,” observed Richard Jr.

Richard Sr. certainly seems to have been a man of integrity. He served on the board of the Federation of the Handicapped (now Fedcap) and was among a group of architects that campaigned against plans to build an office building directly on top of Grand Central Terminal. He was a lieutenant commander in the Navy in the Second World War, commanding the 35th Construction Battalion of Seabees, and received the Bronze Star for ‘meritorious service’.

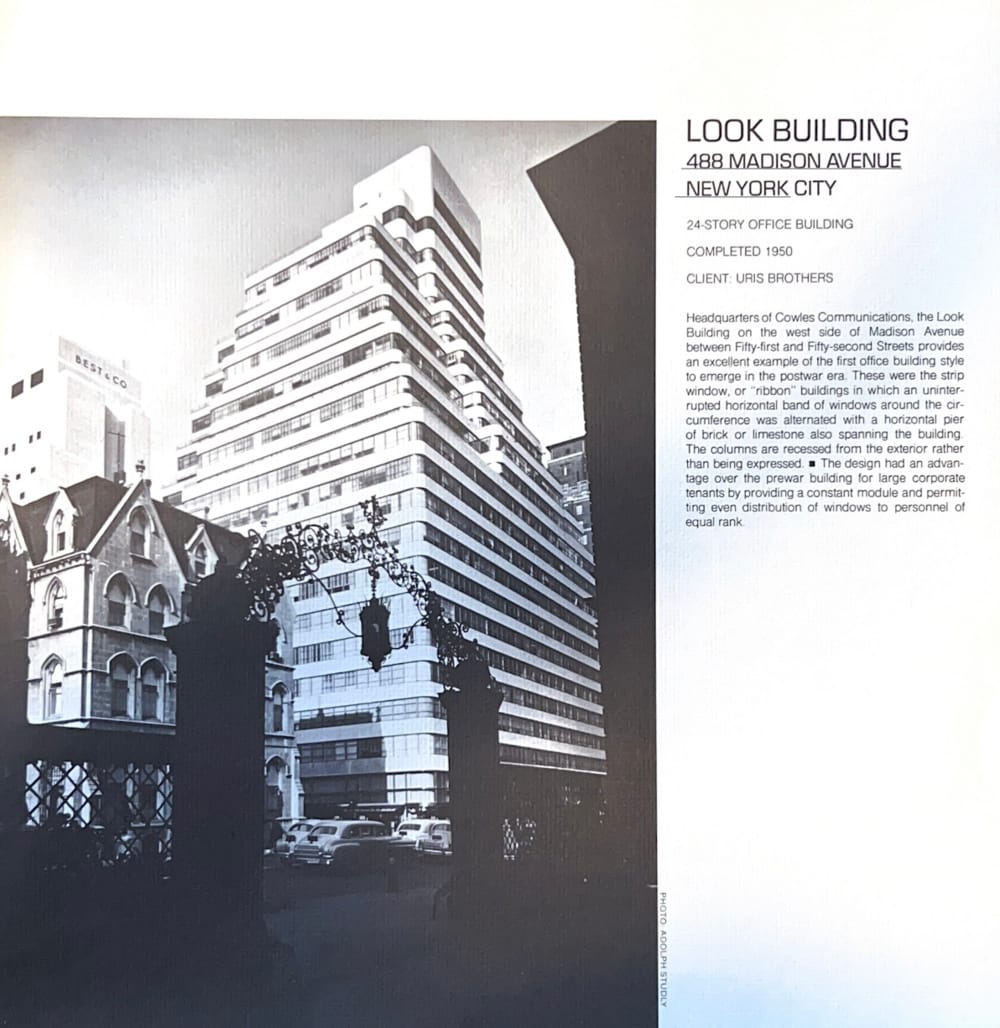

In business, Richard Sr. demonstrated integrity too—refusing to work in South Africa during apartheid. And he showed foresight and intuition. In ‘Mansions in the Clouds’, Steven Ruttenbaum’s 1986 biography of Emery Roth, he explains that Richard Sr. and his brother Julian ‘were able to capture the city’s changing style’. Ruttenbaum suggests the Look Building at 488 Madison Avenue, built in 1949, was one of their last office buildings to incorporate masonry. Within a few years, glass and metal became the norm—and the firm designed 70 such office buildings in the following 20 years.

Richard Jr. thought it sad that his father, who died in 1987, never knew the Look Building would be added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2005. The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission designated it as an official landmark in 2010.

Wednesday, March 12th at 12 PM ET: Join Justin Rivers, Jo Homes, and Robyn Roth-Moise for a virtual walk and talk as we visit Emery Roth & Sons designed buildings in Lower Manhattan, hear exclusive interview clips, and preview future essays!

Richard Jr. had, of course, received many accolades himself. He was awarded a Certificate of Merit by the New York State Association of Architects for Tower East. This was obviously a source of pride as he loved the building—and was delighted that the people who first moved in loved it too. “They threw a cocktail party for me!” he chuckled.

“There I was, I was in my 30s and I was on the top of the world. And this building will always be my favorite building because it truly was my first building.” What’s more, he had poured his heart and soul into it. “According to my wife, I hatched this building. Because during the construction I would go over every weekend and watch it,” remembered Richard.

This post contains affiliate links, which means Untapped New York earns a commission. There is no extra cost to you and the commissions earned help support our mission of independent journalism!

Subscribe to our newsletter