Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

Find out what went on behind the scenes while designing one of NYC's most iconic buildings, now known as the MetLife Building!

Every month this year, Untapped New York will release a new essay from Jo Holmes about the life and work of the late architect Richard Roth, Jr. of Emery Roth & Sons. Each essay explores a different building or developer from Richard’s career, intertwined with stories of his personal life and snippets of exclusive interviews conducted by Holmes and Untapped New York's Justin Rivers (which can be viewed in our on-demand video archive). Check out the whole series here!

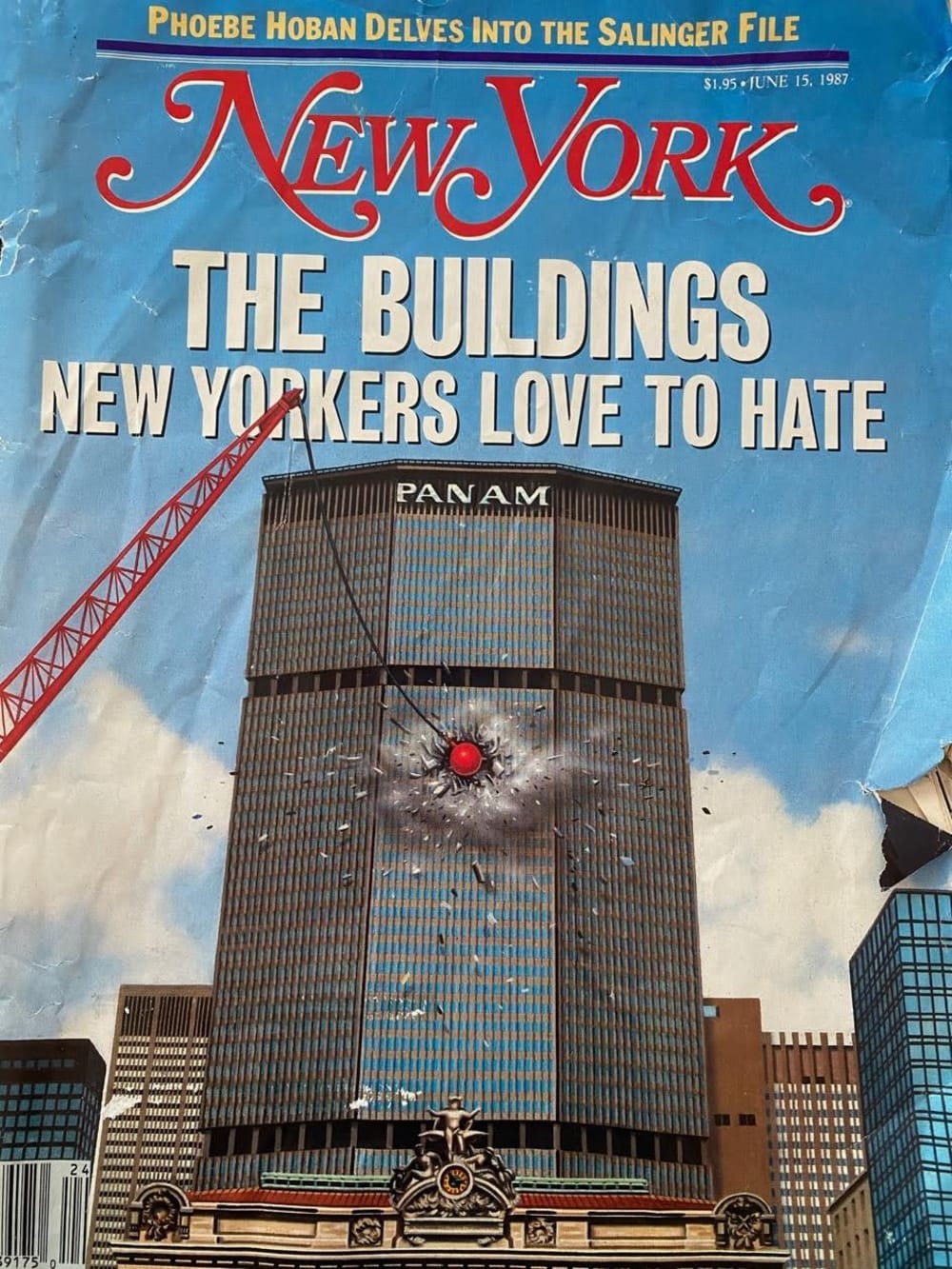

The building that sits directly behind Grand Central Terminal in Manhattan is one many New Yorkers love to hate – and others hate to admit they love. The Pan Am Building (known as the MetLife Building after 1981) was one of Emery Roth & Sons’ most interesting and controversial projects, according to Richard Roth, Jr. Completed in 1962, the 807-foot tall elongated octagonal building was designed in partnership with Walter Gropius, pioneer of the Bauhaus school and a ‘starchitect’ of the period. Richard said the construction was challenging, and working with Gropius (affectionately known as ‘Grope’) was a fascinating experience.

‘Project X’, which would eventually become the Pan Am building in Manhattan, was one of the first jobs thrown at Richard when he joined the family firm. The client, Erwin Wolfson, chairman of Diesel Construction, was trying to attract funding for the ‘Grand Central City Building’ slated for the Park Avenue and 45th Street intersection. Although Richard’s father had already designed a building for the site, Wolfson suggested the firm bring in an architect with a global reputation. “After all, this project was probably the most important project built in New York City at the time, on New York City's most prominent site,” said Richard.

Wolfson and Richard Sr. tasked Richard Jr. with coming up with a list of ten suitable architects. So, Richard made a list of people he most wanted to meet. “The first choice was Mies van der Rohe, who was my idol, second Le Corbusier, then Wright, Gropius, Belluschi, Breuer, Goff, et al,” explained Richard. Things didn’t quite go according to his plan. “Erwin and my father decided that Mies, Corbu, or Wright would be too difficult to work with.” They thought Walter Gropius and Pietro Belluschi, both 70-odd years old, running their own firms and having academic responsibilities, would be too busy to get too heavily involved. “Belluschi, who by the way was a wonderful architect and a wonderful human being, did take more of a backseat, but Gropius took charge and had a big influence on the design,” said Richard.

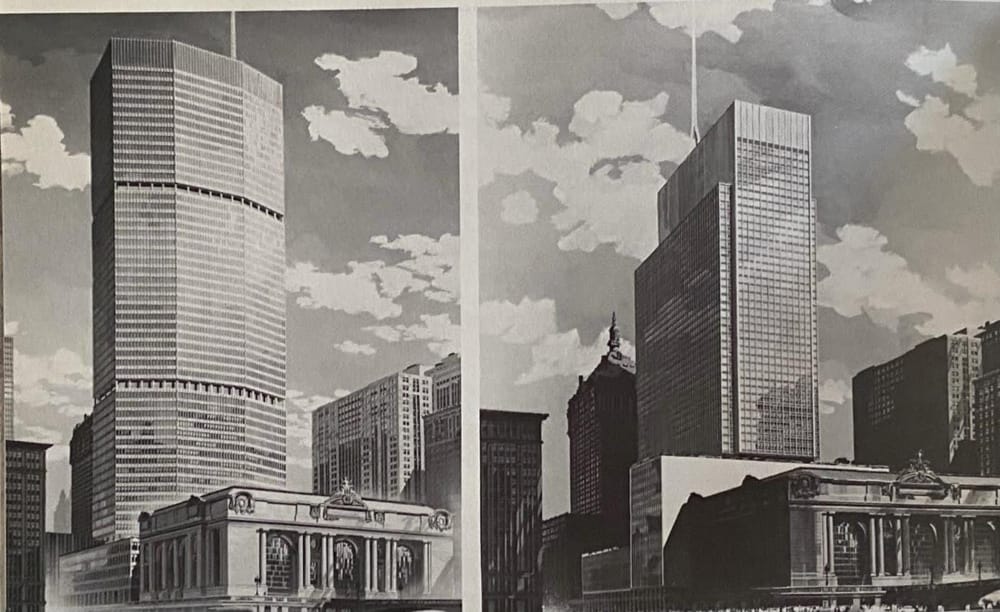

Richard Roth Sr’s original design had been a 60-story glass building going north-south behind the terminal. Controversially, Gropius turned the building to sit east-west. “Gropius also decided he didn’t want to put a glass tower up. He wanted to use a new material called shotcrete,” explained Richard. Shotcrete is a type of precast concrete. This upset one of the prospective tenants, aluminum manufacturer Alcoa. “The Head of Alcoa sales told us they weren’t too happy about moving into a building with very little aluminum. And he said they had some ideas for how to make the building look like shotcrete, but use aluminum,” said Richard. It turned out they were experimenting with dropping stones into liquid aluminum. “Apparently, it was like being on a battlefield: stones were flying everywhere, and everyone had to duck!” laughed Richard. Alcoa abandoned their experiments and eventually moved into the building anyway.

Wolfson had cast his net wide to attract tenants and investors for what would be the world's largest commercial office space. “Erwin had gone to CBS. He had gone to all the banks. He had gone to most of the major companies in the country trying to sell the idea, and we produced drawings showing how we could put their logos on the building. We must have had plans with 40 different logos at the top of the building!” remembered Richard. Eventually, Pan American Airways took a 10 percent stake, and it became the Pan Am Building.

Much has been written about every aspect of the building’s development. But Richard said the challenges involved in its construction were worth reiterating. As the site was just behind Grand Central Terminal, it involved putting columns down through the two levels of tracks while the railroad was operating. Most of the work was done at night, but the lower section was a 24-hour construction site. “Amazingly, nobody got hurt, and nobody got injured in any way. And as I remember, the railroad actually still ran on time,” said Richard.

This feat of engineering led to Emery Roth & Sons being asked to work on other projects involving construction above railroad tracks. “In 1983, I was invited to Singapore to discuss the issues involved in putting buildings over major transit hubs. They were building a subway and talking about doing exactly that. We then had a similar project in Manila.” It also demonstrated they could tackle difficult projects—which won them the Twin Towers and the Citicorp Building in Manhattan. “It certainly led to us doing an awful lot of architecture,” said Richard.

Another notable feature of the building was the art. Wolfson approved several artists to design and make work for the lobby, which provided a pedestrian passageway to Grand Central’s main concourse. They included American sculptor Richard Lippold and German abstract painter and muralist Josef Albers.

Lippold created a three-story wire sculpture called ‘Flight.' Critics thought the area for it was too small, but Richard argued it was up to Lippold to fill the space the way he wanted to. “The space came first! I think Lippold’s piece is really one of the great pieces of art in any building in New York. It certainly does resemble flight – the way the TWA terminal at JFK does,” observed Richard.

Albers’ mural ‘Manhattan’ is 28 feet (8.5 m) tall by 54 feet (16 m) wide and made from black, red, and white Formica. “It was amazing when Albers picked the colors. I’d never realized there were that many blacks, reds, and whites. Our conference room was covered with pieces of Formica, and most of us couldn't distinguish between them. It was very difficult to see the difference between the ones he picked and the ones he threw away,” laughed Richard.

In the middle of the project, Albers came to see Richard. “He shut the doors in the conference room and told me he was very worried. He’d designed this mural for Gropius back in the Bauhaus days and was anxious he’d remember.” Richard told him if Gropius hadn't recognized the mural yet, he wasn’t going to. “That reassured him. And I don't think Grope ever realized Albers had done it before.”

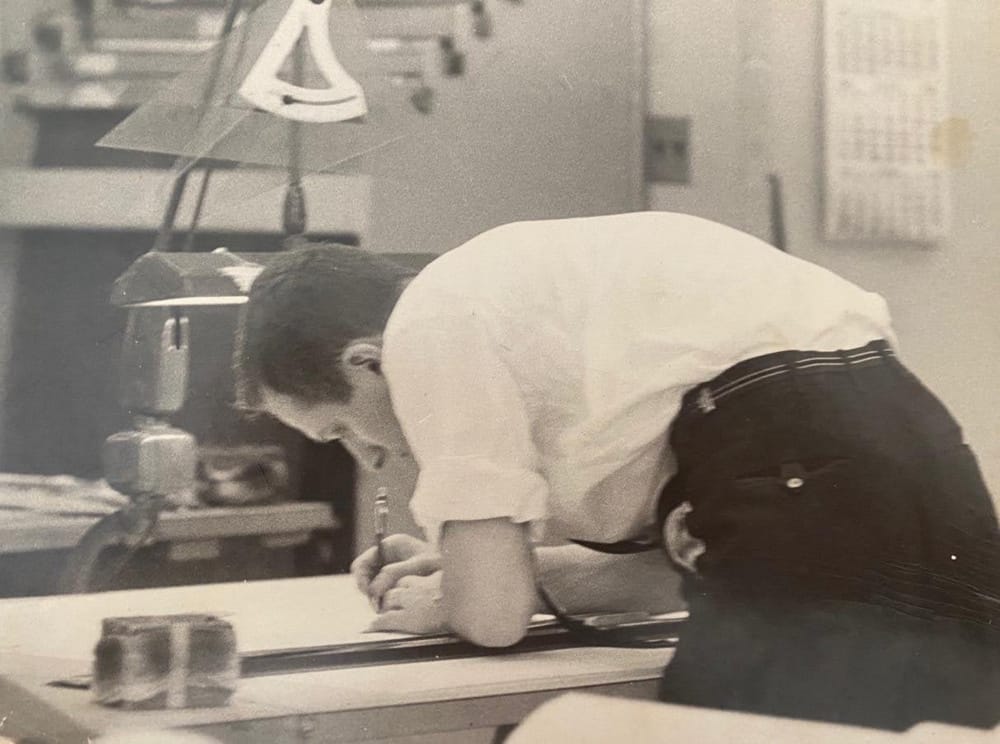

Richard was one of a team of three Emery Roth & Sons architects who traveled back and forth between New York and Cambridge, Massachusetts, to work on drawings with the team at Walter’s firm, The Architecture Cooperative (TAC). He enjoyed getting to know the pioneering—and somewhat enigmatic—architect.

It’s probably hard for New Yorkers to imagine the building sitting north-south now, but the Gropius plan to make it east-west ruffled feathers at the time. There are various theories about the decision to turn the building around, but Richard said Gropius never explained why. “It certainly was a big discussion in our office,” said Richard. “And there were many people, including my father, who to his dying day thought his own design was correct and Grope was wrong.”

Much later, Richard asked Gropius why he’d decided the building should be concrete, not glass as originally planned. “He simply said ‘because I liked it,’” chuckled Richard. What Gropius didn’t like were the materials used in the lobby. Richard came across him sitting near the building one day, looking forlorn. “I sat down next to him, and I said ‘Grope, what's wrong?’ And he said, ‘The granite is terrible! They put up stuff that looks like it belongs in a bathroom.’” Richard noted Diesel Construction ‘deviated’ from some of the specifications for the lobby – and it’s been suggested that was because they were running out of money.

Richard had some treasured possessions from the period. He had to get three letters of recommendation when taking his architectural exam for New York State. He asked Belluschi, Gropius and Erwin Wolfson. “Gropius sent me a copy of his letter, which talked about a great young architect with unbelievable abilities who would be a wonderful addition to the architects in the world…It was a beautiful letter,” said Richard. Three years later, Richard applied for a job with TAC in Rome. “And in response I received a letter saying they did not have room for me.” Richard kept both letters in a book Gropius autographed for him. “So, I have one letter with Grope telling me how good I was, and another telling me I wasn't good enough to work for him!”

The Pan Am building didn’t get a great reception when it opened in 1963. Ada Louise Huxtable of The New York Times, for example, described it as a ‘colossal collection of minimums’ and ‘gigantically second-rate.’ Tragically, in 1977, a helicopter taking off from the roof crashed, killing five people.

So, the building perhaps doesn’t have a happy history, but it’s become synonymous with New York, a cultural icon used in films and TV shows. And, while Richard and his colleagues didn’t agree with some of Gropius’s ideas, Richard was happy to defend the building: “It truly was Grand Central City. You never had to leave the building for anything, you could catch a subway, you could catch a train, you could eat in the building. There was a club at the top of the building you could join. And people who worked there admired the building and loved it.”

Subscribe to our newsletter