Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

Over the years, New York City has aggregated quite a list of nicknames. Some are pretty self-explanatory — “The City that Never Sleeps,” “The City of Dreams,” “Empire City,” — but what’s not so obvious is the history behind New York’s most famous epithet. Where in the world did the “The Big Apple” come from?

For quite some time, the origins of the nickname, “The Big Apple,” were tacked up old wives’ tales. One of the most popular since-debunked myths, entitled the “Whore Hoax,” stated that a Madame named Eve once ran a popular brothel by the same name. However, thanks to etymologist and dictionary contributor, Barry Popik, a far more concrete origin story has come into focus. Popik — who is also widely recognized as the reigning authority on the history of the names “The Windy City” and “hot dog,” among other foods — relates that the earliest roots of “The Big Apple” can be traced all the way back to the late 1800s.

A “big apple” has stood for something desirable or significant since the mid-19th century. In newspapers of the time, the term started to appear in reference to betting. If you’re going to “bet a big apple,” the bet is a sure thing.

The popularization of “The Big Apple,” in reference to New York City is credited to John J. Fitz Gerald, a 1920s journalist and sports writer for the NY Morning Telegraph. For several years in the ’20s and ’30s, Fitz Gerald wrote a horse racing column for the Morning Telegraph entitled “Around the Big Apple.” It debuted on February 18th, 1924.

Fitz Gerald’s inspiration for the name is likely the result of years of subconscious connections. For example, the connection between apples and horses has a bit of a bizarre past considering apples aren’t necessarily a horse’s top food item. Nonetheless, references to horses eating apples appear in various cartoons and short stories dating back to as early as 1892. Fitz Gerald also reportedly overheard the term “big apple” used by African American stablehands in New Orleans, referring to the big horse races in New York City.

Just below the header of Fitz Gerald’s column, this short quote was published: “The Big Apple. The dream of every lad that ever threw a leg over thoroughbred and the goal of all horsemen. There’s only one Big Apple. That’s New York.”

In the horse racing world and the jazz world, “big apple” came to have a similar meaning as the NY Morning Telegraph’s use of “Big Time” — a popular reference for the most prestigious and highest achieving levels of entertainment during the early 1900s.

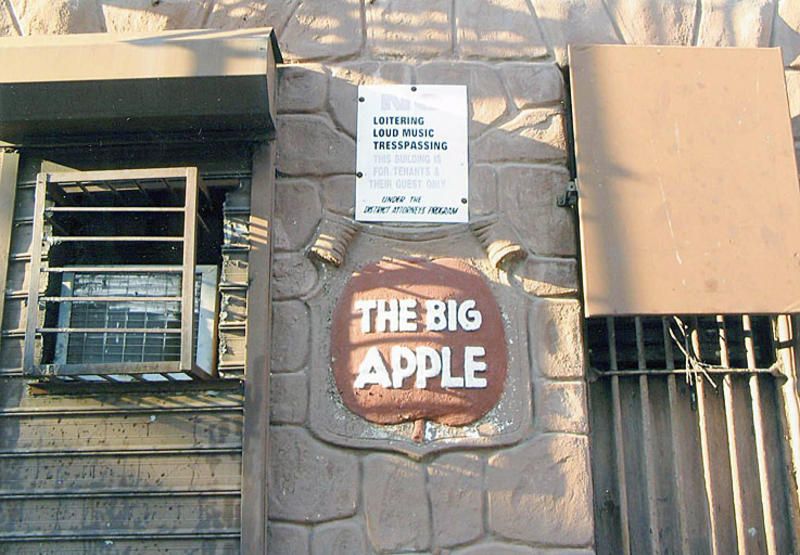

The term “apple” appears in band leader Cab Calloway’s “Hepster’s Dictionary” in reference to Harlem in 1939. Calloway writes that in jive terminology, “apple” means “the big town, the main stem, Harlem.” It was a popular way for musicians to refer to the illustrious jazz clubs of New York City. There were two clubs, a song, and a dance all entitled “Big Apple,” which rose during the jazz explosion of the Harlem Renaissance, most notably The Big Apple Club on 135th and Seventh Ave in Harlem. A “Big Apple” sign fixed on the fake-stone exterior became a staple of the area and played an important role in establishing the nickname. A Popeye’s occupies the building now and the sign, which was removed in the early 2000s, is under private ownership.

A street sign on the corner of 54th Street and Broadway once marked the spot as Big Apple Corner. The sign, installed in 1997 by legislation from Mayor Rudy Giuliani, acknowledged where John J. Fitz Gerald lived at Hotel Bryant (now Hotel Ameritania) from 1934 to 1963.

The “Big Apple” nickname gradually fell out of use after the 1930s until the 1970s, when it was revived for a Tourism Campaign spearheaded by the then-president of the New York Convention and Visitors Bureau, Charles Gillet. Popik’s research suggests that this campaign did crucial work in “eliminating the frequently lampooned nickname of the 1960s, ‘Fun City.'” In her work, Branding New York: How a City in Crisis Was Sold to the World, historian and scholar Miriam Greenberg also explores this further.

Archived articles from the New York Times, published in 1975, credit the campaign with “brightening the city’s image.” A big part of the campaign was passing out Big Apple stickers, which became somewhat of a “worldwide craze.” Celebrities such as Louis Rudin, Alan King, and Tom Snyder, as well as real estate and hotel executives, all jumped in the mix, and an estimated 75,000 stickers had circulated by that point.

Today, there are nods to the Big Apple nickname all over the five boroughs. Every time the Mets hit a home run at Citi Field, a giant apple emerges from the stadium. The Big Apple Circus comes to town. You can learn to dance at Big Apple Ballroom, buy a bouquet from Big Apple Florist, or patronize any of the other countless businesses with Big Apple in their name.

Popik believes there’s more the city can do to bring the history of this moniker to the forefront. He has proposed several initiatives including the re-installation of the Big Apple Corner street sign which went missing in 2021. He also would like to see a dedication of “Big Apple Place” in Harlem to mark the site of the famous Big Apple Club. Writer and artist Regi Taylor, who discovered the Hepster’s Dictionary “apple” reference, would also like to see some sort of official recognition given to Central Harlem and Calloway. Finally, to acknowledge the horse racing roots of the term, Popik proposes the installation of an apple sculpture at Belmont Park.

Coming full circle with the phrase’s etymology, a 1975 New York Times article quoted Gillet as having said, “The symbol has really caught on as a pleasant way of thinking of our city, which is, after all, really the big time.”

Next, check out The Surprising History of the Iconic “I Love NY” Logo and The Story Behind the Famous NYC Greek Coffee Cups

Editor’s Note: This article was originally written by Erika Stark and published on July 5, 2017, and has been updated by Nicole Saraniero on February 16, 2024.

Subscribe to our newsletter