♀️ The Trailblazing Women of Wall Street

Women have long shaped Wall Street—even when history tried to write them out.

How many manhole covers are there in New York City? How are they made? Where do they lead to? In an episode of The Untapped New York Podcast we go over manhole covers 101 and discuss why New Yorkers find them to be such curious objects. We speak with Lisa Frigand, the former Manager of Cultural Affairs at the NYC Department of Environmental Protection, Natasha Raheja, an anthropologist at Cornell University who made the film Cast in India about how manhole are made, and with Justin Rivers, Untapped New York’s Chief Experience Officer, who will talk about his personal experience going down into a manhole. We’ll also look at a unique manhole cover art project that popped up in Greenwich Village. By the end of the episode, you’ll also have the answer to that famous interview question, why are manhole covers round?

If you look down on New York City’s streets, you’ll see quite a cacophony of things from manhole covers, to spray painted symbols, to crosswalks, and more. To kick things off, we first went out onto a Greenwich Village street with Justin Rivers to check out some manholes. The area around Minetta Street is a treasure trove for manhole cover hunters. In just about two blocks, you’ll find dozens of manhole covers for gas, water, sewer and the subway. Of particular note is a DPW manhole cover you’ll find on Minetta Street. If you shine a flashlight down one of the open holes on the cover, you can see the former Minetta Brook flowing. This former fresh-water source for New Yorkers has been long buried and connects into the sewer system now. DPW stands for Department of Public Works, a predecessor of the NYC Department of Environmental Protection. It’s just one of the many abbreviations you’ll find on NYC manhole covers.

On Minetta Lane and the vicinity, you’ll be able to trace the evolution of the NYC Sewer manhole cover from a late-Victorian DPW manhole cover with ornate lettering, to a more industrial DPW manhole cover, to the classic NYC Sewer manhole cover, to one that is also “MADE IN INDIA,” as well as one that simply says “SEWER.”

Each manhole cover is a portal to an underground world below. In popular culture, what lies beneath has been explored repeatedly, perhaps most notably by the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, who would pop a manhole cover to go down to their underground lair that they shared with Splinter, the mutant rat who raised them. The NYC Sewer manhole cover also doubled as a weapon.

Popular fascination with underground systems continues to be manifested in the websites of urban explorers, writers and photographers. This enthrallment can be attributed in part to the rich mythological origins of a fabled underground. In Greek and Roman mythology, Hades is an underground world of arrivals, transition, and temporality. Even if we don’t think of the world under New York City’s streets as a place for lost souls, manholes still remain as a portal between the city as us mortals experience it and the underbelly that supports our existence.

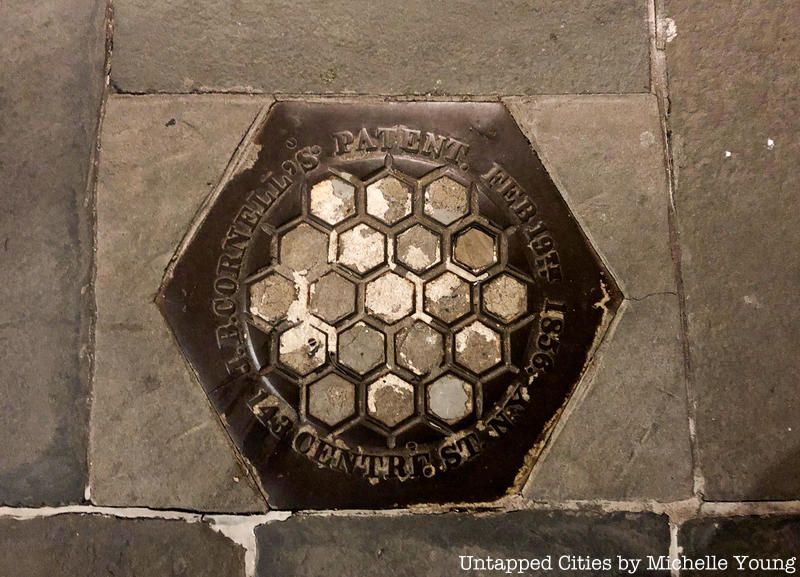

The earliest manhole covers you can find in cities are usually coal hole covers. Made of cast iron, they are generally square or rectangular in shape, sometimes hexagonal. They led to former coal chutes in residences and commercial buildings. Although coal is no longer used to heat homes, you can still find coal hole covers in some of New York City’s oldest districts, like Brooklyn Heights.

But the round manhole covers that most people think of are usually connected to essential services like water, sewers, and power. The advent of modern urban existence in the 1800s necessitated the removal of these services underground. It was part functional but also a utopian ideal, intended to preserve the beauty of cities.

The word “sewer” is defined in old English as “seaward,” which described the open drainage ditches that sloped downwards to the Thames River. The Oxford English Dictionary traces the origin of the word sewer to the old French word seuwiere, meaning “a channel to drain overflow.” By the nineteenth century, the waste from these conduits in all the major cities eventually overwhelmed the ability of natural bodies of water, like rivers and ponds, to self-cleanse. London experienced what is known as “The Great Stink” of 1858. The particular potency of the pollution that summer shut down government and prompted lawmakers to finally enforce and enact public health legislation.

Baron Georges Haussmann, who is credited with laying out modern Paris wrote in 1854, “The underground galleries, organs of the large city, would function like those of the human body, without revealing themselves to the light of day. Pure and fresh water, light, and heat would circulate there like the diverse fluids whose movement and maintenance support life. Secretions would take place there mysteriously and would maintain public health without troubling the good order of the city and without spoiling its exterior beauty.”

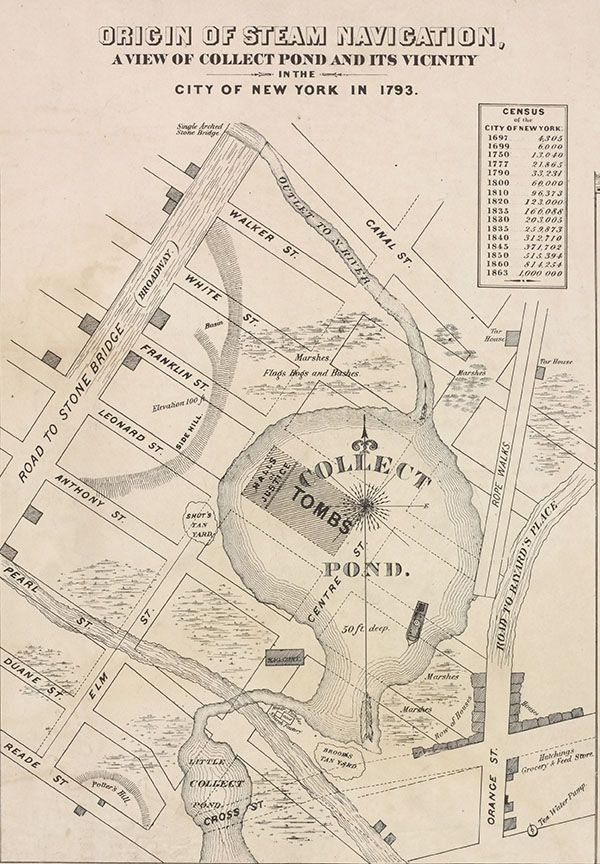

New York City was going through something similar. Like all early settlements, New Yorkers initially relied on existing bodies of water for fresh drinking water. Collect Pond is the most famous, located near the courthouses in Lower Manhattan today. The nearly 50-acre lake was the main source of drinking water, fed by an underground spring. But polluting industries like slaughterhouses, breweries, and tanneries built along the pond’s shores contaminated the water and eventually, the pond was filled in.

By 1811, the natural landscape around Collect Pond was gone and the relentless march of development continued even atop this poorly engineered and polluted landfill. The rough and tumble neighborhood built at Collect Pond became known as Five Points — immortalized in the Martin Scorsese film Gangs of New York. Things got so disgusting with sewage and industrial runoff, they actually had to fill Collect Pond in. A canal was created to drain the pond, but it too became an open sewer and had to be filled in. That’s how Canal Street got its name.

One of the public health crises that emerged from contaminated water was cholera. The first wave of cholera in 1832 killed 3500 New Yorkers. Adjusted for population, that would be equivalent to 100,000 New Yorkers losing their lives in 2020, which is nearly four times the current death toll of COVID-19 in New York City. New York would be hit with four more waves of cholera through 1866, some even deadlier than first wave, making it one of the most disastrous epidemics in New York City’s history.

So, for urgent public health reasons all around the world, sewage systems had to be developed and systems built to bring in clean water. This is how we get some of the oldest manhole covers left in New York City. In 1842, the first Croton Aqueduct was completed bringing fresh water down to the city from Westchester County by means of gravity. It was one of the largest engineering feats of the 19th century. The system opened to great fanfare with a celebration that included a parade down Broadway, the ringing of church bells and the shooting of canons. Gravity-powered fountains in City Hall Park and other places in Manhattan shot water 50 feet up into the air. Manhole covers were needed to access the new exciting system underground.

Tracking historical ephemera, like the oldest manhole covers, is one of my past times. For years, a Croton Aqueduct manhole cover on Jersey Street next to the Puck Building in Soho was often cited as the oldest manhole in New York City. It had the words “CROTON AQUEDUCT D.P.T. 1866” on it. Sadly, roadwork in 2017 wiped away its existence so you won’t find it there anymore. The quest then remained to find the next manhole cover that could be crowned the oldest.

Turns out, another Croton Aqueduct manhole cover — even older than the Jersey Street one — had been here all along. Dating to 1862, as evidenced by the cast-iron numbers, this manhole cover is even better preserved because it sits on a sidewalk. It is however, located in a far less charming spot —across from the much-despised Port Authority Bus Terminal next to Times Square on 40th Street and 8th Avenue.

Another one from the same year was found in Central Park and then in 2021, reader Don Burmeister, who runs the site A Field Guide to New York City Manhole Covers, tipped us off to an even older one! Dating to 1861 and located in Central Park this manhole cover currently holds the title of New York City’s oldest in our book.

Another Croton Aqueduct manhole cover, dating to 1866, is located inside Thomas Jefferson Park in East Harlem. It’s likely the second oldest in New York City. But the most common manhole covers around today are the ones that say NYC Sewer or are connected to Con Edison, ConEd for short, which runs steam and electricity lines under the city’s streets.

To learn more about manhole covers, I spoke with Lisa Frigand, who worked for ConEd for 34 years starting in 1978. She retired as the Manager of Cultural Affairs at ConEd in 2012 but is still involved in the arts, making her own ceramics and embroidery. She tells me that when she was working at ConEd, the company had about 250,000 manhole covers and that they weigh between 200 and 300 pounds each. A spokesman at ConEd confirmed her estimate, telling me that the company manages approximately 265,000 structures which include manholes, service boxes and transformer vaults. But then the NYC Department of Environmental Protection also gave me their numbers, and they have about 350,000 manhole covers across the five boroughs! So for now, I’m crowning the DEP with having the most number of manhole covers in the city!

A good number of manholes covers have the words MADE IN INDIA on them in large, all capital letters. Have you ever wondered why that is? To get down to the bottom of this, I spoke with Natasha Raheja, an anthropologist and professor at Cornell University and the director of the documentary Cast In India, which is an exploration into how manhole covers in New York City are made. Her quest to understand the connection to India took her to Howrah, a city in West Bengal, where some of the NYC Sewer manholes are being manufactured. In our latest podcast episode, Natasha explains what materials manhole covers are made from, how they’re manufactured, and some additional fun facts. You can watch Cast in India on Apple TV, Google Play, Kanopy, and Amazon Prime (in select countries).

Manhole covers are also made in the United States. ConEdison tells me that it gets most of its manhole covers from a foundry in Michigan called East Jordan, but they work with a few other US-based foundries as well.

New York City is a fountain of inspiration for artists. Even the most mundane of objects have been turned into art, and the manhole cover is no exception. In the year 2000, nineteen custom manhole covers appeared in Greenwich Village with a cryptic phrase on it: “In Direct Line with Another and the Next.” The words looked like they had been almost stamped onto a generic looking manhole cover. The letters were in all capitals, but everything was a little crooked. If you came across it, you might look around you for something it might reference, perhaps in direct line with it. But it wasn’t quite as direct as that.

On the rim of the manhole cover, you would see the names of three organizations involved: The Public Art Fund, Con Edison and Roman Stone Company. It was an art initiative from the Public Art Fund, a non-profit dedicated to putting art in public spaces. The design itself came from Bronx-born artist Lawrence Weiner, whose text-based art has been in museums and public spaces all around the world. He was one of the pioneering artists who began using language as art. New Yorkers may remember his more recent installation in 2009 on the piers of the Battery Maritime Building, where the ferries to Governors Island leave from. It read: “AT THE SAME MOMENT” in large red lettering.

Lisa Frigand, whom we spoke to earlier, was actually instrumental in getting Lawrence Wiener’s manhole cover project executed, when she was Manager of Cultural Affairs at ConEd. She worked with Roman Stone Company, a foundry on Long Island, to get the manhole covers designed to spec and made. I asked her what the phrase, “In Direct Line with Another and the Next” meant to her — and you can hear her answer in the podcast episode! You can find at least one of Weiner’s manhole covers remaining, as part of the Whitney Museum’s collection – it’s embedded in the floor near the entrance to the museum.

One of the most pressing questions I had about manholes is what it’s like to go down one. In 2009 I missed my own opportunity to do just that. Self-made urban archeologist and local icon, Bob Diamond, had discovered and excavated the famed Atlantic Avenue tunnel in Brooklyn and was giving tours. Built in 1844, it’s considered the world’s first underground transit tunnel. Chalk it up to being in my 20s and in a rock band at the time. I was out late performing and just couldn’t get up in time to go. I thought, I’ll be able to go again, but this is New York City and all off-limits things get shut down eventually. Fortunately for us, Justin Rivers did make it and you can hear all about his experience in the podcast episode.

Before we close out, have you figured out yet why are manhole covers round? My contact at the DEP says, “The principal reason that manhole covers are round is so they won’t fall into the manhole.” If a manhole is square, rectangular or even oval, it can fall into the manhole if you insert it at an angle or vertically. Yikes!

Over the last 160 years, New York City’s underground has become increasingly complex. We spoke today about the most common manhole covers you can find in the city, the NYC Sewer manhole covers and the ones for ConEd. But you’ll also find manhole covers for the subway, for the water system, and for telecommunication companies like Verizon and its subsidiaries, which include companies it acquired like the New York Telephone Company and Empire City Subway (ECS for short). Empire City Subway has nothing to do with the modern subway, but was formed after the Great Blizzard of 1888 which took down much of the city’s overhead electrical infrastructure. The aim of the company was to build underground ducts for telecommunication services.

When companies go defunct, sometimes their manholes covers remain for a long time afterwards, becoming part of the city’s historical record. While the number of manhole covers in New York City is a constantly fluctuating number, what’s clear is that they continue to be an object of fascination for New Yorkers. Look down next time you’re walking around and see what you discover about New York City’s history and how the city works. Cowabunga!

Check out the rest of the episodes of The Untapped New York Podcast on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever else you get your podcasts!

Next, check out 10 of the Most Unqiuex NYC Manhole Covers

Subscribe to our newsletter