Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

New York City may not be as old as some of the cities in Europe where catacombs and crypts have become major tourist destinations, but it does boast a number of its own spooky subterranean burial spaces. While some of these spots are off-limits to the public, others can easily be visited. Some have been known for centuries, and others were recently discovered. Keep reading to find out where the creepiest crypts and catacombs lie beneath the streets of New York City. If you dare…

Thanks to heavy tourist promotion, the catacombs of the Basilica of St. Patrick’s Old Cathedral in Nolita have probably become the most well-known in New York City. We recently overheard French tourists on the Roosevelt Island tram desperately trying to explain to locals how they had been to the “basilique” with the catacombs. Besides its famous catacombs, the basilica is also known for its appearance as a setting in The Godfather II and its sheep that “lamb”scape the grounds.

The Basilica of St. Patrick’s Old Cathedral is one of the last places where you can still be buried in Manhattan, though that privilege comes with a hefty price. A resting place in the catacombs costs about $7 million, while a niche in the above-ground columbarium costs much less. If you’d like to enter the catacombs as a living person, you can hop on a guided tour and visit the resting places of notable New Yorkers, from bishops to businessmen.

New York Marble Cemetery in the East Village is not your typical cemetery. You won’t see any gravestones, mausoleums, or columbarium. Instead, you’ll see a well-manicured lawn and blooming flowers, inviting benches, and long stone walls lined with marble plaques. Doesn’t seem so spooky from above ground, but here, instead of interring coffins directly in the earth, they were interred in underground marble vaults. These enclosures were created for fear of diseases spreading from corpses. The are 156 marble vaults the size of small rooms buried ten feet below the ground. They are arranged in a grid of six columns by twenty-six rows. To gain access to the vaults, visitors needed to remove stone slabs, with some requiring keys to open.

Incorporated in 1831, a year before New York City Marble Cemetery (which is just one block away), the cemetery was New York City’s first non-sectarian burial place open to the public. The last burial occurred in 1937. Today, the landmarked site serves as a public gathering space. You can visit and enjoy a picnic on the grounds during Open Gate Days which occur at least once a month.

The catacombs of The Green-Wood Cemetery are open to the public for guided after-dark tours and for concerts. Access is gained by using an old-fashioned dungeon-like key, which unlocks the iron gates out front. The staff of Green-Wood Cemetery calls the space “30 Vaults,” a reference to the number of vaults inside. Located underneath a hill, the catacombs date to the early 1850s.

Unlike a mausoleum, which usually holds only one family, the catacombs were built to hold multiple families in one place. Jeff Richman, The Green-Wood Cemetery’s historian, calls them, a “sort of apartment house for above-ground interment…a middle-class option for people who wanted the luxury of above-ground interment without the expense of constructing something on [their] own.”

The most famous person buried there is Ward McAllister, the Gilded Age high society tastemaker who coined the term “The 400.” “The 400” is a reference to the elite of New York society, dubbed such because 400 is the number of people that could fit in Mrs. Astor’s ballroom. McAllister was not as wealthy or blue-blooded as those he advised. life, so burial in the Green-Wood catacombs was a fitting end for someone of his stature. Richman says McAllister would have been “quite chagrined to know that the catacombs are now locked up and access is very limited.”

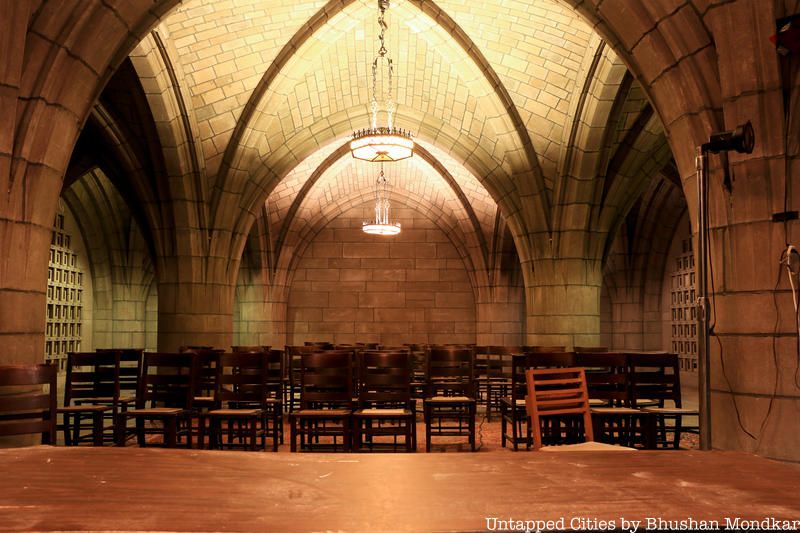

Tucked away beneath an elegant and striking block in Hamilton Heights, accessed through the Trinity Church Cemetery, there’s a rarely-seen hallowed space carved from rough stone. The cavernous crypt has perfect acoustics and history thickly hangs from every rafter. Simply known as the Crypt, this space is a hidden gem of New York City owned by

The cemetery and the surrounding blocks served as the home base for John James Audubon, the naturalist and artist known for his work in ornithology (the study of birds). When Audubon passed away, he was buried in the cemetery. In the 1920s, cemetery space in the city was scarce and in high demand. To create more room for burials, the crypt’s walls were prepared to hold cremated remains. This renovation made the church the first in the United States to have its own columbarium (a building with niches for storing funeral urns). Today, the acoustics of the space make it a cozy and intimate venue for live jazz concerts among the dead.

Just a block away from New York Marble Cemetery, you’ll find New York City Marble Cemetery. The similarly named cemeteries were created by the same developer in the 19th century, but have no connection today. They do, however, share other similarities. Like New York Marble Cemetery, this cemetery also has interments buried in marble vaults beneath the ground, again due to fear of disease. To get into the vaults, an authorized visitor would lift up the square stone marking the grave and descend via ladder to the vault below.

What sets this cemetery apart from its near neighbor is its size. There are estimated to be over four thousand bodies buried here, including some interesting characters. One notable resident is a man named Preserved Fish. Founding Father and 5th U.S. President, James Monroe was interred here for a few years before being removed to his native Virginia. The cemetery is generally closed to the public, but you may get lucky and gain access during a rare special event.

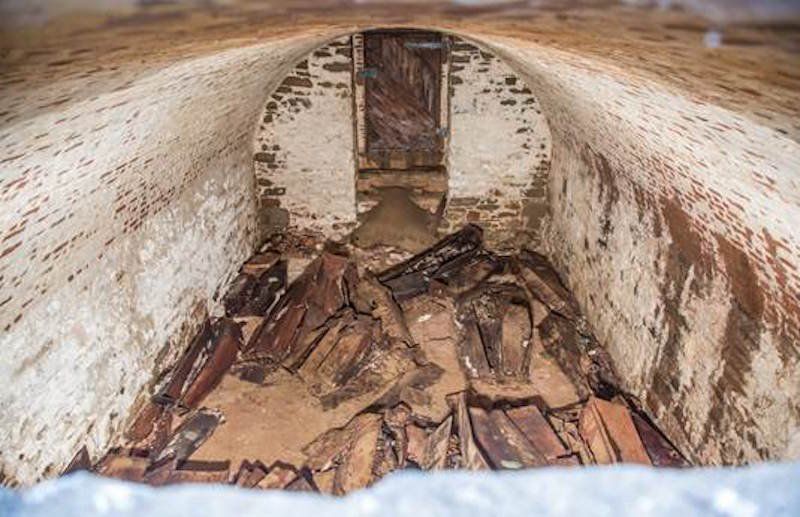

Below Trinity Church Wall Street is the formerly forgotten vault of the Bleecker family. Bleecker family burials in the vault took place from 1791 to 1884, meaning the vault pre-dates the current Trinity Church Wall Street structure, consecrated in 1846. After the final burial in 1884, save for the burial of one set of ashes years later, the family vault largely fell out of use, and out of mind. In 1981, Richard Bleecker, a descendant of the Bleecker family asked the church if the vault was still accessible. This was the first request the church received from a Bleecker descendant in decades, and they weren’t sure. It took nearly another twenty years to gain access.

In 2000, Richard and church staff descended beneath the floor of the church and uncovered the intact vault. According to another Bleecker family descendant who recounted the vault’s story for CNN, tragedy struck just two years later when construction workers disturbed the coffins. The vault was eventually restored with a new entrance, new shelves for ashes, and a gravel floor. A ceremony was held inside the church to reconsecrate the vault in October 2016. Other artifacts have been found under Trinity Church, including old bottles and battery oil, but so far nothing like the buried treasure Nicholas Cage finds in National Treasure.

The Cathedral of St. John the Divine is the largest cathedral in the world, but remains unfinished. A guide to the Cathedral from 1921 estimated that construction could last up to 700 years based on the true Gothic building methods used to create it. On the exterior, this incompleteness is evident in its asymmetrical facade. Inside, the off-limits crypt remains a work in progress.

To lay the foundation of the cathedral, builders had to dig 300 feet down. This excavation project was funded by J.P. Morgan. The Guastavinos did the ceiling of the crypt, which is laid out in the shape of a crucifix. Today, that crucifix is truncated due to the unfinished plan. The walkway of the crypt follows the layout of the church above, with studio spaces named after the chapels atop the subterranean space.

The Cathedral has a long history of artists in residence who used the studios in the crypt, including Greg Wyatt, the sculptor who created the Peace Fountain on the southwest side of the Cathedral Close, and Philippe Petit, the World Trade Center tightrope walker.

In April 2019, a fire broke out in the crypt of the cathedral, destroying and damaging “many paintings, icons and pieces of furniture,” reported the New York Times. After years of repairs and reconstruction, the crypt is now open to the public on very rare occasions around Halloween (and for private tours with Untapped New York Insiders!). Keep an eye out for your next chance to join a “Crypt Crawl.”

Standing 149 feet tall in front of a grand 100-step granite staircase, the Prison Ship Martyrs Monument in Fort Greene Park rarely opens for visitors. The over 100-year-old structure stands on top of the remains of thousands of American prisoners, both men and women, who died during the Revolutionary War. After winning the Battle of Long Island and control of Fort Putnam (later rebuilt and renamed Fort Greene during the War of 1812), the British detained thousands of American men and women on prison ships anchored in Wallabout Bay. On the ships, the prisoners experienced overcrowding, contaminated water, starvation, and disease. Ultimately, 11,500 prisoners died. The bodies of those who died were haphazardly buried along the shore.

In 1873, after multiple relocations, some of the remains were finally laid to rest in Fort Greene Park, known at the time as Washington Park. Encased in twenty-two boxes, the remains were interred in a 25×11 foot brick vault. Washington Park was a newly designated public space designed by landscape architects Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, the same men who designed Central Park and Prospect Park. In response to public demand for a permanent memorial to the prison ship martyrs, the renowned architectural firm of McKim, Mead, and White was hired to design one. The towering Doric column we see today was dedicated in 1908. If you wish to visit the remains inside the monument, The Society of Old Brooklynites hosts a visit inside once a year, but you have to be a member of the society to enter. In order to join, you must have lived or worked in Brooklyn for the past 25 years.

Washington Square Park is already rather ghoulish, with its prior history as a potter’s field – the city’s burial ground for the unclaimed and poor. In 2015, two burial vaults with human remains were discover just east of the park by workers who were in the area to complete a NYC Department of Design and Construction (DDC) water main project.

The DDC, in partnership with The Landmarks Preservation Commission and Chrysalis Archaeological Consultants, assessed the significance of the findings and cataloged the contents without actually disturbing the vaults. In addition to the vault entrance, human skeletal remains of a dozen people were found in the first vault. Both vaults are eight feet deep, fifteen feet wide, and twenty feet long. The experts who analyzed the vaults believe they are from the 19th century and likely related to the former Cedar Street Presbyterian Church.

A pair of copper doors, just below the altar, lead to the crypt at St. Patrick’s Cathedral on Fifth Avenue. The crypt, which is rarely opened to the public, is small and has a “black, speckled floor, light gray marble, and fluorescent lighting… [and a] gold prie-dieu, or kneeling prayer desk,” according to The New York Times. The crypt is home to many of New York City’s former Archbishops and Cardinals, including John Cardinal O’Connor and Edward Cardinal Egan. Additionally, Pierre Toussaint, a former slave and philanthropist, is buried in the crypt. Toussaint was originally buried at St. Patrick’s Old Cathedral. When Pope John Paul II declared Toussaint to be Venerable, a step towards possible canonization, Toussaint was reinterred at St. Patrick’s Cathedral.

Next, discover 10 more of the spookiest places in NYC!

Subscribe to our newsletter