Last Chance: The Annual Orchid Show Soars at the New York Botanical Garden

The vibrant colors of Mexico come to NYC for a unique Orchid Show at NYBG!

Image Courtesy of Gehry Partners, LLP

Architectural critic Paul Goldberger’s new biography about Frank Gehry, Building Art: The Life and Work of Frank Gehry, addresses the architect’s trials and triumphs in New York City. The city represented, Golberger writes, “the unattainable, the mountain that he would try repeatedly to climb, only to find himself sliding back down.” Gehry broke this spell finally with the IAC Building on Manhattan’s west side and the residential skyscraper, New York by Gehry. But prior to these, the city seemed to always evade him, apart from the cafeteria he designed in the Condé Nast headquarters in Times Square.

Here are five projects Gehry designed for the city that were never realized:

In 2000, the New York Times Company held a “starchitecture” design competition for a new headquarters on Eighth Avenue. Competitors included the usual suspects of the late ’90s and early aughts like Norman Foster, Cesar Pelli, David M. Childs of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, and Frank Gehry.

According to New York Magazine, Gehry said he had actually been commissioned for the job. His proposed design was a twisted high-rise with the Times logo on the side. He allegedly pulled out after a meeting with the developer, Forest City Ratner, who told Gehry he had to be in New York for a meeting that Gehry couldn’t make. This makes the relationship far more antagonistic than is likely true for that time period, as Gehry would work again with Forest City Ratner for Atlantic Yards and New York by Gehry After Gehry dropped out of the Times building, the commission was given to Renzo Piano, architect of Paris’ Centre Pompidou.

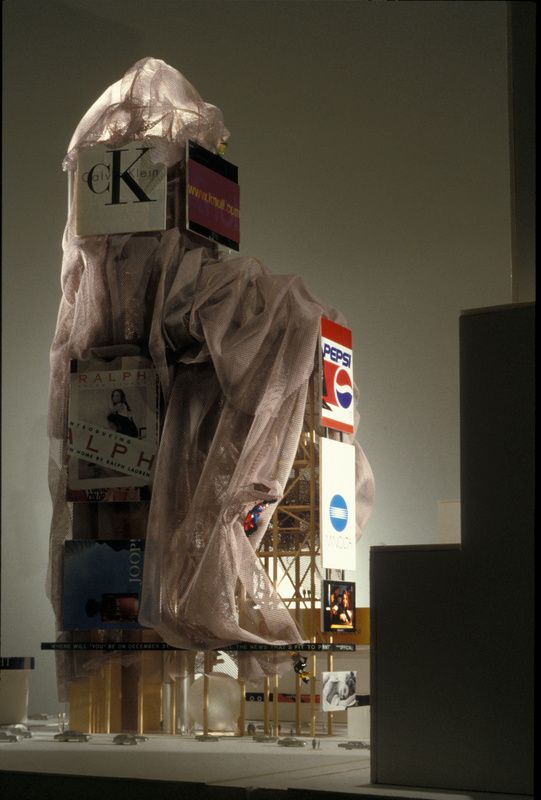

Ian Schrager, prominent hotel owner and former manager of Studio 54, purchased property for his first hotel from scratch to be built on the south side of Astor Place between Fourth Avenue and Lafayette Street. In Around Washington Heights: An Illustrated History of Greenwich Village, author Luther Harris writes that Schrager chose the location because of its unique position in the city landscape and because of the iconic Astor Place Cube. He reportedly wanted “a shimmering design that would become a worldwide icon.”

Schrager sought out Gehry after a falling out with his first architects, Rem Koolhaas and Jacques Herzog of the Swiss firm Herzog and de Meuron, Gehry’s 300-bedroom design was meant to resemble a draped statue but the project was dropped after 9/11.

Gehry had hoped to do the Lower East Side what he did with Bilbao, Spain. His proposed $678 million design was going to include a gigantic titanium cloud with a glass underbelly over the East River. The New York Times wrote the proposed plan was a “polymorphous, 400-foot-tall building designed by Frank Gehry on Piers 9, 13 and 14, south of the Brooklyn Bridge in Lower Manhattan.” Outside the ribboned building, he proposed six acres of open space that would’ve connected the Old Slip platform to Maiden Lane.

However, in 2002, Solomon R. Guggenheim dropped the proposal due to financial constraints and the economic situation. The New York Times stated that many had anticipated this blow. Carl Weisbrod, now head of NYC Department of Planning, then president of the Alliance for Downtown New York said that he “was disappointed, but not surprised.”

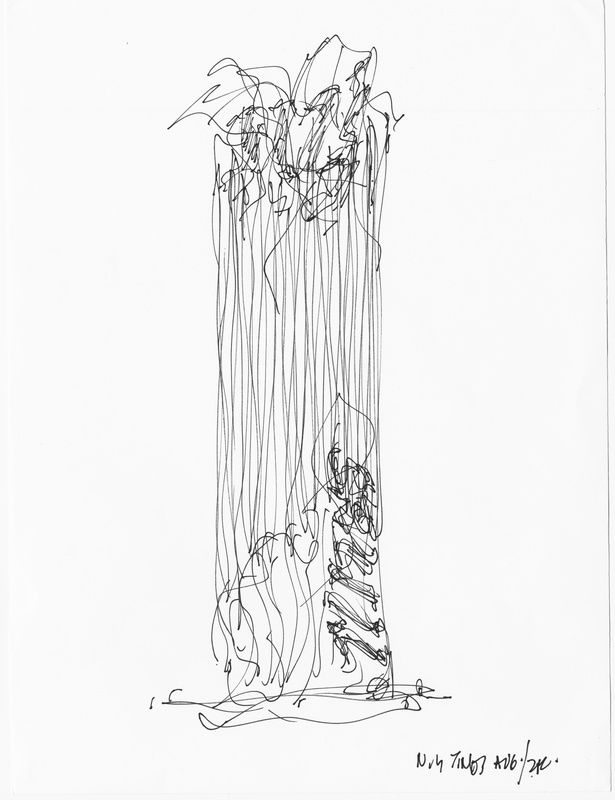

Gehry’s design for One Times Square was not dissimilar to his design for the Astor Place Hotel – he proposed to cover the building in fabric. In 1996, Warner Bros. leased One Times Square and asked Gehry to revamp the landmarked tower. Aiming to relate the building to the studio, Gehry “designed a giant cuckoo clock, with a chain metal skin that slipped over the entire building like a fabric skirt. When the clock chimed, Superman would swoop out on tracks and pull back the mock drapery, revealing a gaggle of Warner characters, including Bugs Bunny and Elmer Fudd.” However, the project stalled after the projected budget was over $80 million. As reported by the Los Angeles Times, Gehry wasn’t called again after the initial meeting.

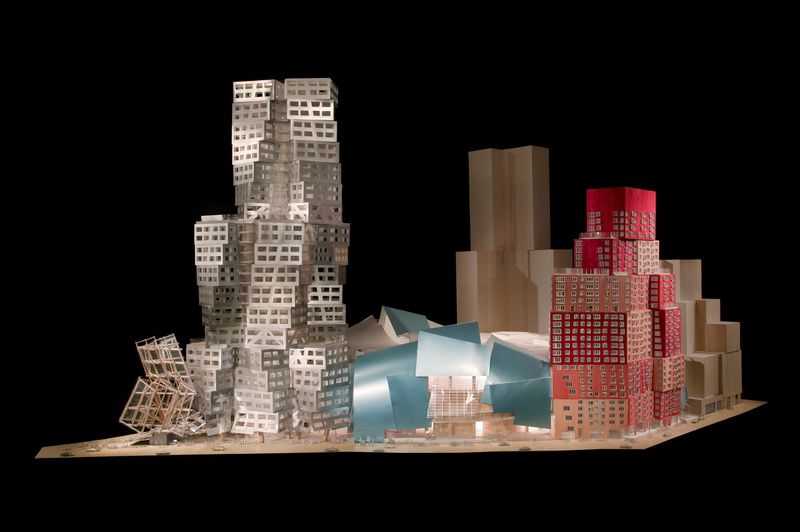

Perhaps Gehry’s most devastating blow was the cancelation of Atlantic Yards in 2009. With Atlantic Yards, Gehry wanted to break the boundaries that he had broken with Bilbao and Los Angeles’ Walt Disney Concert Hall. According to New York Magazine, he envisioned building “a neighborhood from scratch.” The proposed plan included 17 buildings for a 22-acre development right next to the residential neighborhood, Park Slope, in Brooklyn. While the main attraction was the basketball arena, the design also included a high-density residential and commercial development. It was projected to cost $1 billion.

The original (2008) LIRR tracks in Brooklyn underlying Atlantic Yards.

Gehry worked on the design and project for six years, but in 2009 developer Forest City Ratner, which had once represented 35 percent of Gehry’s business, pleaded financial straits and fired Gehry from the project. New York Magazine said that in doing so, Ratner “betrayed the city, blighted a neighborhood he promised to transform, validated his opponents, and blew a colossal opportunity to bring great architecture to a city that badly needs it.”

It was announced in June 2007 that Frank Gehry would design the first playground of his career in Battery Park, Manhattan’s southernmost point. Unfortunately, Gehry’s $10 million plans far exceeded the $4 million budget and complications from Superstorm Sandy brought the project to an impasse. Gehry’s design included several dizzying slides, a “green” comfort station and a child-sized birdhouse.

Next, read about the secrets of New York by Gehry, the architect’s first skyscraper in New York City and check out these wild alternatives to the Whitney.

Subscribe to our newsletter