Fiber Arts Take Over a Former Seaport Warehouse in NYC

See waterfalls of fabric, intricate threadwork, massive tapestries, and more!

Of the grand monuments scattered throughout New York City, many have an equestrian theme. Taken as a whole collection by theme, these statues reveal not only the history of New York and the United States, but also the history of other countries around the world. Here are twenty to look out for as you explore the city.

If you enter Union Square Park from the south, you will be greeted by none other than George Washington. Washington is depicted reclaiming the city from the British on November, 25, 1783, Evacuation Day (the day the British evacuated the last of their troops from New York City). The statue was dedicated on July 4, 1856, and is the oldest statue owned by the New York City Parks Department. It was sculpted by Henry Kirke Brown and John Quincy Adams Ward and the base was designed by Richard Upjohn.

Fun fact: It has actually moved from its original locations in Union Square. You can see a vintage photo of where it was originally in the book Broadway by Untapped Cities founder Michelle Young.

Next: Check out what else can be found in Union Square Park.

Standing in the Manhattan’s Grand Army Plaza, off 5th Avenue and Central Park West is the gilded statue of General William Tecumseh Sherman. It was designed by Augustus Saint-Gaudens, and was the artist’s last major work. Sherman is most famous for his service during the Civil War, especially his infamous March to the Sea, which recent scholarship has shown to be more targeted than originally thought. The quote “War is Hell” is attributed to Sherman and interestingly he was sent a letter by the man who assassinated President Garfield in hopes that Sherman would break him out of jail.

Sherman spent his post-war years in New York City, living on the Upper West Side, where he died in 1891. In 1903, New York City City honored the general with a statue of him being led by Victory. These days, the statue forms a nice contrast to the outdoor art installations just behind it by Public Art Fund – the latest, a giant granite grocery list.

Read more about NYC sites related to the Assassination of President Garfield

The equestrian statue of President Theodore Roosevelt was the final piece of the larger Roosevelt Memorial that makes up the Central Park West entrance to the American Museum of Natural History. The Roosevelt Memorial, which consists of the museum’s east facade, the Theodore Roosevelt Rotunda with murals illustrating Roosevelt’s life, and the Theodore Roosevelt Memorial Hall. Conceived by the State of New York in 1924 to honor the late president, the memorial was dedicated in 1936 by thousands of dignitaries including President Franklin Roosevelt, Colonel Theodore Roosevelt Jr., and Governor Herbert Lehman.

The equestrian statue designed by James Earle Fraser was dedicated in 1940. It depicts the president as a Rough Rider, next to a Native American and an African American. The statue and memorial arch, modeled on the Arch of Constantine, form the focal point of Theodore Roosevelt Park, ensuring the President’s legacy is not forgotten.

Next check out The Top 12 Secrets of the American Museum of Natural History

The statue of Joan of Arc, on Riverside Drive, was the first statue of a woman to be placed in a New York City park. It was designed by Anna Vaughn Hyatt Huntington, who received the Chevalier of the Legion of Honor by the French government for her work on the statue. The statue was commissioned to commemorate the 500th anniversary of the birth of the saint. It was dedicated on December 6, 1915, in a ceremony presided over by the French Ambassador and Mrs. Thomas Alva Edison who pulled the cord to unveil the statue.

The pedestal incorporates a World War I shell-shattered pilaster from the Rheims Cathedral and part of the walls of the prison where Joan of Arc was held in Rouen. (Another piece of which can be found in the Smithsonian Museum and can be seen in the Castle). Copies of the statue can be found in the Garden of the Bishops in Blois, France, the Legion of Honor in San Francisco, Gloucester, Massachusetts and Quebec City, Quebec.

Next check out 9 Sites Associated with Women’s History in NYC.

Franz Sigel was a German revolutionary who emigrated to the United States after the Revolutions of 1848. In New York, Sigel became a teacher and wrote for The New York Times and a few German publications. During the Civil War, Sigel became a Major General in the Union Army, where he was instrumental in keeping Missouri in the Union. After his death in 1902, a park was named in his honor in the Bronx, near his former Grand Concourse home.

In 1904, Karl Bitter, whose New York works included the temporary Dewey Arch and the doors of Trinity Church, was commissioned to create a statue to honor Sigel. The statue was dedicated in October 1907, on Riverside Drive and 106th Street, with more than 10,000 people in attendance.

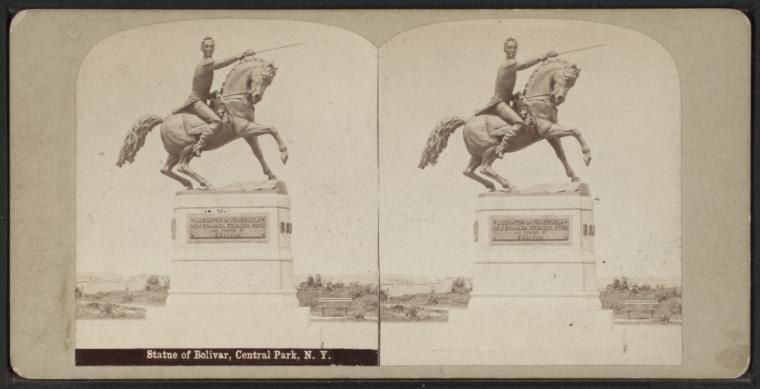

The northern terminus of the Avenue of the Americas is flanked by the statues of three South American revolutionaries. The first of these South American heroes to be honored was Simon Bolivar. In 1884, the people and Government of Venezuela gifted a statue of Bolivar to Central Park. The statue stood near 81st Street, on the west side of the park, on what became known as Bolivar Hill. The statue, designed by R. De Las Cora, was not well received and as a result, was removed from the park.

The Original Statue of Simon Bolivar, Central Park via NYPL

The Original Statue of Simon Bolivar, Central Park via NYPL

In 1921, President Warren Gamaliel Harding presided over the dedication of a new statue of Bolivar on Bolivar Hill, designed by Sally James Farnham, whose work can also be found at Woodlawn Cemetery. With the creation of the Avenue of the Americas, the Venezuelan Government requested that the statue be moved to a more prominent and contextually appropriate location. Initially, the Art Commission denied this request, despite pressure from the State Department, and instead voted to improve the site where the statue was located.

It took until 1951 for the statue to be moved to its current location, paid for by the Government of Venezuela.

The 1950 statue of General Jose de San Martin was a gift of the City of Tucuman (or alternatively Buenos Aires). San Martin aided Argentina, Chile, and Peru in gaining independence from Spain. The statue was given in reciprocity for a statue of George Washington that the people of North America had given to the City of Buenos Aires a few years earlier. The statue of San Martin is a replica of Louis Joesph Daumas’ 1862 statue of San Martin, located in Buenos Aires.

The statue was fabricated in Argentina and shipped to New York aboard the Rio Chico. However, once it arrived in New York, the statue remained in limbo first at the pier and then in an unopened crate in a warehouse in Central Park because Mayor O’Dwyer was having issues convincing the Board of Estimates to appropriate the funds to erect the statue. Its placement at the foot of Central Park led to infighting between Robert Moses, then Parks Commissioner, and City officials. Its location was aided by pressure from the State Department, which urged the City to place the statue in a prime location to aid Pan-American relations.

At 11:30 on Tuesday, May 18, 1965, the statue of Cuban patriot and martyr Jose Julian Marti statue was dedicated complete with the Department of Sanitation Band (with a performance by the Department of Sanitation Band). The statue faced a long and complicated journey to its dedication at northern end of the Avenue of the Americas. It was the last major equestrian commission by artist Anna Hyatt Huntington, at the age of 80. Huntington was personally recruited to sculpt Marti by the Cuban Government, under Batista. She was paid $100,000 for the work, which she donated to Hispanic charities. The statue was completed in May 1959 but it would take six more years for the statue to be erected.

For six years, an empty plinth stood next to the statues of San Martin and Bolivar on 59th Street. Huntington’s statue was given to the City in November 1958 or May 1959 (depending on the source) after which point it disappeared. In 1960, the Marti statue was discovered in a Bronx storage yard, strategically hidden under a tarp. The City, at the behest of the State Department and NYPD, refused to erect the sculpture out of fear it would become the site of clashes between pro- and anti-Castro groups. As a result of the City’s inaction, a group of Anti-Castro Cuban exiles attempted to erect a plaster model of the statue atop the plinth. Ultimately, the 600-pound statue proved too tall to hoist atop the base and it was placed next to it, with the hope that it would be too heavy for the police to move. Within hours, the police arrived and somehow confiscated the statue (as they more recently did with the Snowden and Trump statues).

By April 1965, the statue was rediscovered in a Central Park maintenance yard. When asked about its present predicament by The New York Times, a spokesperson from Mayor Robert F. Wagner’s office responded “How come you guys know where it is?” The City finally decided it was time to finally erect the sculpture. On May 18, 1965, the 70th anniversary (plus one day) of Marti’s death, the statue was dedicated in the presence of Anna Hyatt Huntington and Cesar Romero (Marti’s grandson and the actor best known for playing the Joker in the Adam West Batman series).

Today, there is a push by the Friends of Jose Marti to erect a replica in Havana.

Wladysław II Jagiełło was the king of Poland who defeated the Germans in the Battle of Grunewald in 1410, in what The New York Times described as “one of the most crushing pre-Eisenhower defeats ever met by the German military might.” A statue of Jagiello, designed by Stanislaus Ostrowski, was brought to New York for the Polish Pavilion of the 1939 World’s Fair. It was a replica of a statue of King Jagiello in Warsaw, which the Germans melted into bullets. After the fair ended, the statue was placed into storage where it remained for five years, since the statue could not be returned to Poland during the war. A committee decided to raise funds for the statue to remain in New York City and be moved to Central Park. The statue was dedicated in 1945, on the 535th anniversary of the Battle of Grunewald, with over two thousand people present in the pouring rain.

See more of the remnants of the 1939 World’s Fair.

The equestrian Peace sculpture (also referred to as Horsewoman) was gifted to the United Nations by Yugoslavia in 1953 and designed by Antun Augustinčić. The statue is eighteen feet high and surmounted on a twenty foot pylon, with stone from what is now Croatia. Augustinčič is well regarded in his native Croatia, though Peace is his only sculpture on display in the United States.

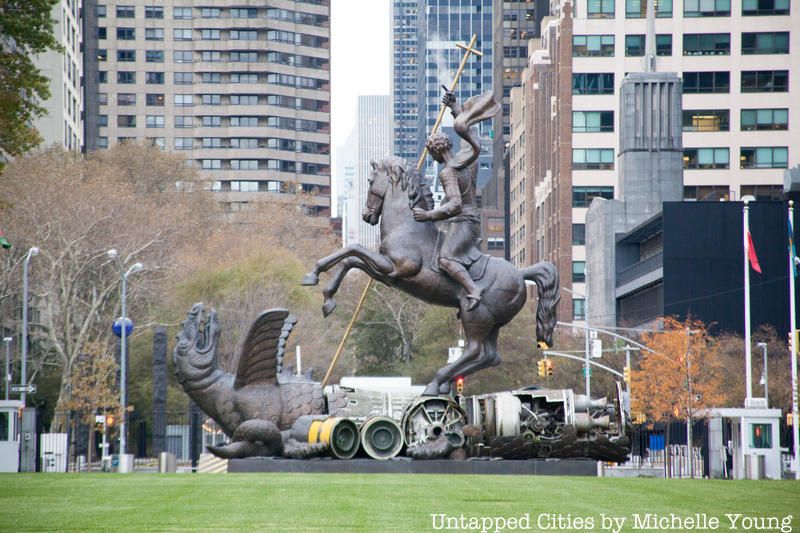

Good Defeats Evil was donated to the United Nations by the Soviet Union in 1990, in honor of the United Nation’s 45th anniversary. The 39-foot bronze statue depicts St. George slaying a dragon, made from Soviet and American nuclear missiles destroyed under the 1988 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty. The statue was designed by the Georgian artist Zurab Tsereteli, based on a dream he had after witnessing Soviet and American children pretending to destroy missiles after the I.N.F. treaty. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the statue caused a stir when it was unveiled, with some calling it an eyesore.

Audubon Terrace is the cultural mecca designed by Archer M. Huntington on the former estate of John James Audubon. While, some of the of the Terrace’s tenants have long departed, it is well worth checking out the underrated and often overlooked Hispanic Society of America and the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

In the courtyard, Huntington’s wife Anna Hyatt Huntington, created a group of sculptures to complement the institutions housed at Audubon Terrace. Amongst the most impressive as a statue of El Cid on his horse Babieca surrounded by four figures representing the Spanish Order of Chivalry, Don Quixote on his horse Rocinante, and Boabdil, the last Moorish king of Spain atop his trusty steed.

Next check out our coverage of the composer Charles Ives’ studio in Audubon Terrace.

Inside the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Memorial Arch in Brooklyn’s Grand Army Plaza, are two overlooked reliefs of Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant. The former presidents were sculpted by William Rudolf O’Donovan (who served in the Confederate Army) and their horses by Thomas Eakins in 1895. The reliefs capture the moment Lincoln and Grant were reviewing the Union troops besieging Richmond in March 1865. Lincoln is shown doffing his hat to the troops. Though they were not originally beloved by Brooklynites, the reliefs have since become noted for being the only depiction of Lincoln on horseback at the time and one of the only sculptures by the painted Thomas Eakins.

Frederick William MacMonnies, who more famously designed the Nathan Hale and Civic Virtue statues, created the often overlooked equestrian statue of General Henry Warner Slocum, hidden amongst the foliage of Grand Army Plaza. The statue was originally erected at Bedford Avenue and Eastern Parkway, in 1905. President Theodore Roosevelt was present at its dedication in what The New York Times described as the greatest Memorial Day in Brooklyn’s history.

General Slocum was moved to the Fifteenth Street entrance of Prospect Park due to the building of the subway on Eastern Parkway (or alternatively a traffic tower). The statue was moved to its current location in a “wooded knoll” (to put it nicely) in Grand Army Plaza, in 1927. Aside from at one time being a well regarded Union general and for saying “Stay and fight it out” at the Battle of Gettysburg, Slocum has faded into obscurity. His name is even barely visible on his statue and his sword has been stolen multiple times.

Today, Slocum is most known unforunately for the steamship named after him that sank in 1904 causing the deaths of over 1,000 New Yorkers, the largest disaster in New York history before September 11th, 2001.

Brooklyn’s aptly named Continental Army Plaza in Williamsburg contains a statue of George Washington at Valley Forge. The statue was designed by Henry Merwin Shrady, who won a design contest, and was dedicated in 1906. About 15,000 people attended the dedication of the 35 foot tall, 7,000 pound, bronze statue.

William Ordway Partridge, who also designed the statue of Samuel Tilden on Riverside Drive and Thomas Jefferson and John Howard Van Amringe at Columbia University, was chosen to by the Union League Club to design a bronze statue of General Grant. The statue was unveiled on April 27, 1896 on what would have been Grant’s birthday and the dedication ceremonies were led by Governor, and former vice president, Levi Parsons Morton and General Grant’s grandson. The 1,200 pound, sixteen foot, statue is located in what today is known as Grant Gore in Crown Heights though originally was referred to as Grant Square.

Prospect Park‘s Horse Tamers are located near the southwest corner of the park where Prospect Park Southwest and Parkside Avenue intersect. Frederick MacMonnies’ sculpture is an allegory of Triumph of Mind over Brute Strength and was inspired by the equestrian statues that flank the entrance to the Champs-Elysees. On the way to Prospect Park, one of the sculptures was lost in a shipwreck off Newfoundland. The horse was ultimately found and restored by MacMonnies before being dedicated in 1899, on a pedestal designed by Stanford White.

Visitors to the ninth street entrance to Prospect Park are greeted by the Lafayette Memorial. Daniel Chester French designed the ten foot high bronze relief, which was a gift to the City by Henry Harteau, a French-Brooklynite glass insurer. The statue is likely based on a painting by Jean-Baptiste Le Paon entitled Lafayette at Yorktown. As a result, some historians believe (though it is far some settled) that that the man on the left of the sculpture is James Armistead, a slave from Virginia who served under Lafayette and was ultimately freed and became a slave owner himself.

Next check out the two other monuments honoring the Marquis de Lafayette in Union Square and Harlem.

Duane Park is a small (barely one tenth of an acre) triangle surrounded by Duane Street to the north, south, and west, and Hudson Street to the east. The park was named after James Duane who helped draft the Articles of Confederation and was New York’s first mayor after the Revolutionary War. The land for Duane Park was purchased in 1797 for five dollars from Trinity Church and was the first parcel of land to be acquired by New York City with the intent of being turned into a public park. The park’s fence contains horse heads, whose origins are a mystery.

Yet, Duane Park is not one of the ten smallest parks in Manhattan – check the out here.

Image courtesy of Skinner, Inc. www.skinnerinc.com

On April 26, 1770, an equestrian statue of King George III was dedicated in Bowling Green. King George III was not the statue’s intended subject. After the repeal of the Stamp Act in 1766, a number of cities decided to erect a statue of William Pitt, the British Prime Minister, who instrumental in the repeal of the Stamp Act. However, the New York elders thought it unwise to have a statue of Pitt when there was no statue of King. As a result the City commissioned Joseph Wilton to design statue of both men.

The gilded lead statue, on a white marble base, was placed in Bowling Green surrounded by a ten foot high fence. The fence posts were topped with depictions of the royal crown. Six years later, in the midst of the Revolutionary War, the statue’s fate was sealed. On July 9, 1776, the Declaration of Independence was read at the head of each brigade of the Continental Army posted at New York. In the furor created from the public reading, British symbols around New York City were destroyed culminating in the pillaging of the statue of King George III and the removal of the crowns atop the fence. The remnants of the statue were sent to Litchfield, Connecticut and made into bullets for the war effort. A few pieces from the statue, that were possibly hidden by loyalists in Connecticut, can be found at the New-York Historical Society, with additional pieces auctioned off over the years.

See more remnants of Dutch New Amsterdam and pre-Revolutionary relics like the fence at Bowling Green in our tour the Remnants of Dutch New Amsterdam:

Tour of The Remnants of Dutch New Amsterdam

The most recent addition to the equestrian monuments is the America’s Response Monument, which was rededicated on September 13, 2016 in Liberty Park. The monument contains a fragment of steel from the World Trade Center and was commissioned anonymously by a group of Wall Street bankers who had lost friends in 9/11. The statue honors those in the American armed forces that served in response to 9/11.

Next, check out the Top 12 Secrets of Prospect Park.

Subscribe to our newsletter