Would you consider the ubiquitous elevator worthy of a shrine? Apparently this humble-seeming mode of transportation has more devotees in New York City than you’d think. There are two different elevator museums in the city–the Long Island City Elevator Historical Society and The Museum–both totally different but equally worthy of perusal. However, how would you distinguish one elevator museum from the next? Having been to both, I’ll say this: it all depends on whether you want to learn about elevators or have your understanding of their function revolutionized.

Long Island City Elevator Historical Society

The Long Island City Elevator Historical Society is incongruously situated in a cavernous car garage in an industrial corner of Queens. Having taken a few long minutes to locate the entrance, I ask founder Patrick Carrajat, why an elevator museum here? He replies, “Well, how do most New Yorkers get around? They take a cab to a building, then an elevator up to their apartments. Fitting, huh?”

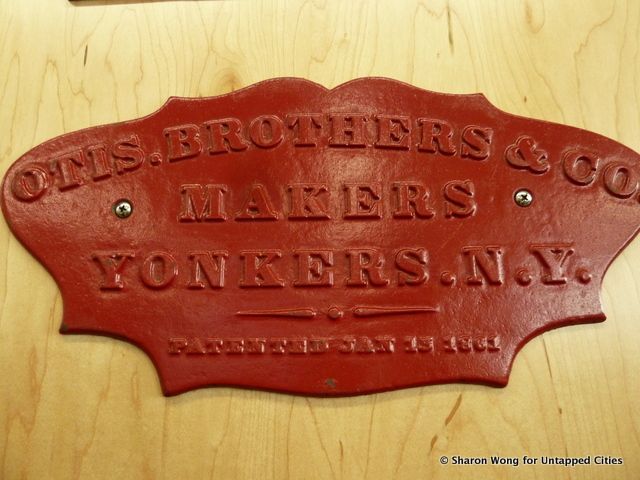

Carrajat is both a loquacious, charismatic guide and passionate historian/collector. The wide variety of paraphernalia in the airy, well-lit elevator museum was amassed over decades. He immediately takes me over to a small elevator plaque labeled “My First Object, 1955.” He tells me, “This is what started it all, I got this from my father when I was eleven.” It is far from the oldest object in the room, but there is no mistaking its powerful nostalgic value.

Next to Carrajat’s First Object are a great many other plaques from the late 19th century.

This classic red sign is Otis Elevator’s oldest existing sign, dating from 1881. Carrajat chuckles when he tells me about how Otis has been trying to purchase this sign from him in vain.

Also of significance is a sign dating from the 1890s, when Otis had offices in Boston, Philadelphia and New York City in addition to Yonkers. Business was clearly booming.

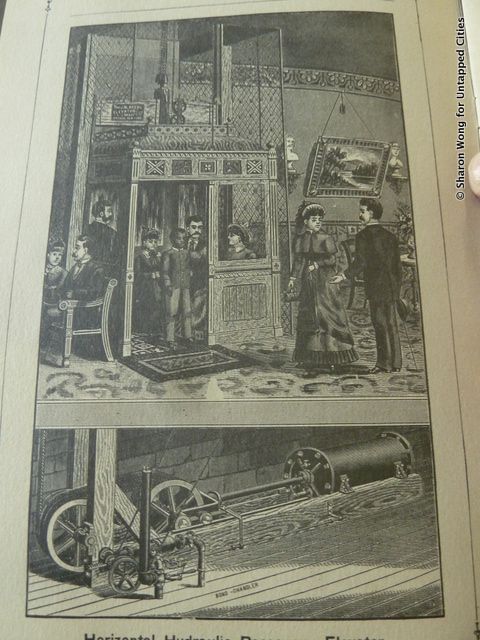

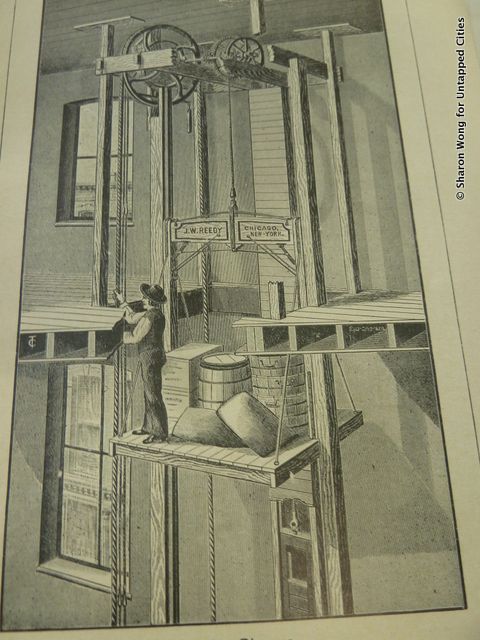

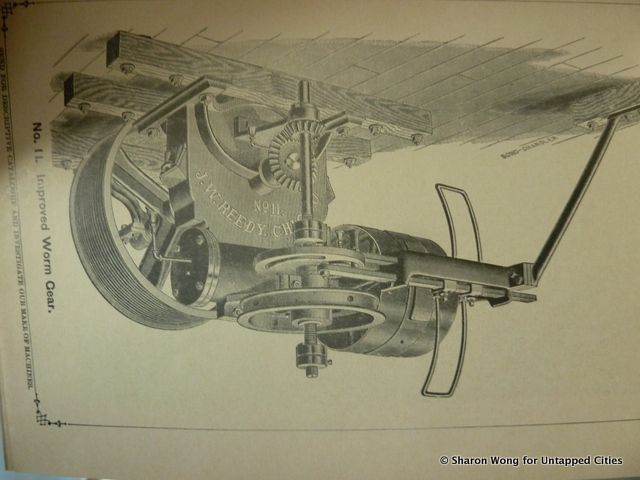

Also of great interest in the elevator museum are several old instructional manuals, many of which have detailed engravings that were each individually produced by an artist.

Of course, an elevator is nothing without its parts, of which Carrajat has many. There are car switches of many hues, some of which were props in television shows that were never filmed.

For me, the most interesting artifacts are the memorabilia once produced by elevator companies for their customers.

At the end of the extensive tour, I have to ask Carrajat, why an elevator museum at all? Perhaps I could have anticipated his reply. His father was in the industry and Carrajat used to savor the days when he was allowed to come help at work. “After all,” he muses, a faraway look in his eyes, “I think it’s a human thing to want to do what your parents do.”

The LIC Elevator Museum may be visited only by appointment. Book yours now at 917-748-2328.

The Museum

In The Museum, you won’t learn much about elevator history or its inner workings. But it’s impossible to forget about them whenever you make a visit, as the museum is actually in one. Yes, the entire exhibition space is encapsulated within a green-lit freight elevator on Cortlandt Alley in Tribeca, a nondescript little lane off Canal Street. The space is so small that my guide, Natalie, has to send visitors off to wait in a nearby coffee shop when there are more than three visitors. She told me, “I feel bad, but most people want to linger. There is just so much to see.” And she was completely right. The amount of rich narrative content packed onto just one of the glass shelves in this elevator museum is staggering.

Initially, the economical size of all the objects on display in the elevator museum seemed to be the only common denominator. There were potato chip packets, Disney backpacks, tubes of toothpaste, molds of genitals and other assorted bric-a-brac that seemed like the flotsam and jetsam of everyday life. But then again, that is precisely what the Museum’s current exhibit is all about, the various collections of things we tend to accumulate over the years. Filmmakers and founders, Benny and Josh Safdie and Alex Kalman, are fascinated by small objects that unexpectedly reveal a larger cultural narrative of humanity.

The first thing I perused was the row of sparkly Disney backpacks.

I soon discovered that they were built for a rather grim purpose in mind: to protect children from bullets. Each backpack is lined with the same material used to line anti-ballistic vests. After the 2012 school shootings, sales for these have gone up 500%.

Then, there was the row containing various colorful splatters of fake vomit.

According to their collector, Peter Allen, the body produces its own artistic materials and its canvas may be a sidewalk, a wall, the toilet bowl and even our own hands. Gravity, of course, is the main deciding factor.

Potato chip packets collected from around the world reveal that what each nation considers to be common, desirable flavors may surprise the average American.

An entire shelf was devoted to Chinese paper funeral effigies burned for the dead, should the dead need shoes, instant noodles or an iPhone.

There was a convicted serial killer photographed next to a friend.

And who could forget the Nazi soap carvings, produced by the only man in Alaska ever to kill a fellow inmate?

As disparate as all these objects and their respective tales may seem, I felt that they were all delivering a resounding collective message: what we may think when we first view an item and its actual significance does not always compute. A piece of shrapnel by the road may in reality be as momentous as a bomb fragment, but we’ll most likely kick it out of our way without a second thought while hurrying to work.

The Museum’s current collection is showing until July 1. Book an appointment at info@Mmuseumm.com. If you want to submit your own objects and collections for review, you may do so by emailing submissions@Mmuseumm.com. To learn about the elevator museum’s previous collection, click here.

So, which elevator museum would you want to visit? The one that tells the elevator’s story or the one where the elevator serves as a medium for the stories of other overlooked objects? Pick your poison.