With some of the oldest New York City churches dating back to the 1700s, they have been host to George Washington, runaway slaves, Boss Tweed, and 9/11 workers. New York City churches have also adapted to the changing neighborhoods and communities around them, serving as hospitals, meetinghouses, comfort stations, museums, and even synagogues. However, the buildings themselves remain largely unchanged from when they were built, complete with secret rooms and passageways that are all but forgotten today. Below, discover the ten oldest churches still standing in New York City, starting with the most recent.

10. St. Augustine’s Episcopal Church (1829)

St. Augustine’s Episcopal Church was built on Henry Street in 1829 using stone that was quarried at Mount Pitt. Even though the church was not finished until 1829, it was consecrated by the third bishop of New York in 1828. The wooden belfry that used to be on top of the church’s tower was removed in the early 1960s, but the bell that it housed used to serve as the local fire alarm.

One notable feature of the church is the hidden slave galleries. There were two of these cramped, dark rooms, one on either side of the organ on the balcony at the back of the church. Slavery in New York State became illegal in 1827—the end of a gradual emancipation process that started in 1799—but New York continued to recognize the slave status of those who came with their masters from other states. When Eliza Magear Tweed died in 1876, Boss Tweed, who was a fugitive at the time, hid in one of these slave galleries so he could see his mother’s funeral, which was held at St. Augustine’s. Later, these rooms were used as a place to hold Sunday school for children. While most churches have covered up or gotten rid of their slave galleries, St. Augustine’s calls attention to theirs with art exhibits and tours that honor the memory of those who once sat in them.

9. New Utrecht Reformed Church (1828)

The New Utrecht Dutch Reformed Church was built on the site of the old New Utrecht schoolhouse, near the place where the original church (built in 1700) once existed. During the Revolutionary War, the 18th-century church was used by the British as a hospital, a prison, and then a riding school. The British troops also held target practice in the church’s cemetery, which led to the destruction of many of the tombstones.

The church moved to its current location in 1828. The original church from 1700 was dismantled and the church’s stones were used to construct the new one. In front of the church, a 100-foot Liberty Pole is planted on the lawn to mark the place of the first American flag in New Utrecht. This is the sixth Liberty Pole that New Utrecht has erected. The original was placed there in 1738.

8. Bialystoker Synagogue (formerly Willett Street Episcopal Church) (1826)

Forty years before the Bialystoker Synagogue made its home at 7 Willett Street (now Bialystoker Place) in 1905, the building was home to the Willet Street Episcopal Church. Built in 1826, the Federal-style church was made of Manhattan schist, which had been quarried on Pitt Street. There are only three other buildings in Lower Manhattan from the Federal period that are made out of fieldstone.

There is no written record confirming this but oral tradition maintains that the synagogue was a stop on the Underground Railroad. A hidden door in the corner of the women’s gallery leads to a ladder going up to an attic. It is believed that this concealed room was a place for runaway slaves to take refuge.

7. New Lots Community Church (1824)

An offshoot of the Flatbush Church, the farmers of New Lots obtained permission in 1823 to build their own local church since the other one was too far away. The farmers lacked the money to buy materials or hire builders, so they collected timber from the woods near their property. This process was aided by the fact that a hurricane had taken down many mighty oak trees in the area two years prior. The community saw these fallen trees as a gift from God, which they accepted gratefully.

When the church’s frame was complete, the townsfolk gathered for the “roof raising.” With the exception of the plasterwork, every part of the church was made by the local community that it was to serve. It is a very plain structure with little ornament beyond the gothic style arched windows. Completed in 1824, the original wooden building still stands today, which is a testament to the sturdy craftsmanship of the settlers.

6. First Chinese Presbyterian Church (1817-19)

The building that currently stands at 61 Henry Street first opened its doors in 1819 as the Market Street (Dutch) Reformed Church. Predating the trend of Gothic Revival Style churches by nearly two decades, the building’s pointed Gothic windows and doors are among the earliest in Manhattan. The Dutch Reformed Church disbanded in 1864. In 1866, the church entered its second phase of existence as a Presbyterian house of worship when the Church of the Sea and Land moved in.

Established in the previous year, the Church of the Sea and Land was a Presbyterian congregation for sailors, former sailors, and their friends and families. The Church of the Sea and Land dissolved in 1972, but they passed the torch to the First Chinese Presbyterian Church, with whom they had shared the space since 1951.

5. Old St. Patrick’s Cathedral (1809-15)

Built between 1809 and 1815, the Basilica of St. Patrick’s Old Cathedral is the original Cathedral of the Archdiocese of New York. 260 Mulberry Street, the site chosen for the church, fell within the second cemetery of St. Peter’s Church (the original graveyard had already become full), so the graves on the site needed to be relocated before construction could begin. When the church opened, St. Patrick’s assumed control of the cemetery, and it continued to be the primary burial place for the Catholic community in New York City. St. Patrick’s Cemetery expanded outward until 1824, and the church also built crypts beneath the church—the only catacombs in Manhattan.

Anti-Catholic violence was common at the time, so St. Patrick’s constructed a 10-foot brick wall around the property in the 1830s to keep the cathedral and its cemetery safe. Mobs frequently stormed the cathedral, attempting to break windows and burn down the building. Between 1835 and 1855, attacks against St. Patrick’s grew so intense that armed parishioners needed to be stationed outside the church to keep watch at night.

4. St. Mark’s-in-the-Bowery (1795-99)

St. Mark’s-in-the-Bowery is the second oldest church structure in Manhattan. It is also the oldest location to be continuously occupied by a church. In 1654 Governor Peter Stuyvesant built a small chapel for his family’s personal use. The chapel and the land remained in the possession of the Stuyvesant family for over 100 years before they sold it to Trinity Church in 1793. In 1795, on St. Mark’s Day, the cornerstone of the new church was laid on the same site.

Despite the two-year gap between the sale of the first church and the construction of the second, an official statement by the church in 1899 asserts the bodies of the Governor and his family, who had been buried under the chapel when they died, “preserved the hallowed character” of the location. John McComb Jr., the architect who built City Hall, completed the building in 1799, but the steeple and porch were added later. Although Trinity had paid for the church to be built and was, according to the charter of 1697, the only parish church in New York City, Alexander Hamilton helped incorporate St. Mark’s as an independent Episcopal parish. The church is still in operation today.

3. Flatbush Reformed Church (1793-98)

The Flatbush Reformed Church, on Flatbush and Church Avenues, is one of the oldest churches on Long Island, and it was the first on Long Island to be incorporated by the state in 1784. The original church in Flatbush was built in 1654, under the direction of Governor Peter Stuyvesant. It was built in the shape of a cross and had a stockade for protection against Native Americans.

The current church edifice, constructed 1793-1798 on the site of the previous one, is made of Manhattan schist that was quarried at Hell Gate. The foundation includes stones from the original building. Beneath the church are buried American soldiers who fought in the Battle of Long Island. The church occupies the site in longest continuous use for religious purposes in the city. The clock and bell in the church’s tower date to 1796 and are of Dutch make. The bell has tolled for the death of every United States President and Vice President.

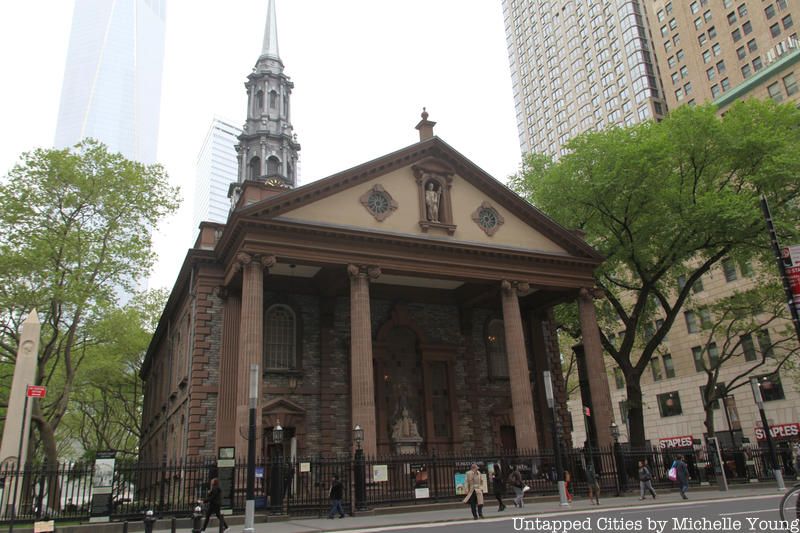

2. St. Paul’s Chapel (1764-66)

St. Paul’s Chapel, on Broadway between Fulton and Vesey Streets, was built in 1766 to serve the expanding congregation of the Trinity Church Wall Street parish. Not only is it the oldest church in Manhattan, but it is also the oldest extant public building in the city. The Church’s steeple, which was added to the building in 1794, contains two bells, the first of which was made in England in 1797. The second bell was added in 1866 to celebrate the church’s centennial.

President George Washington made St. Paul’s his place of worship in 1789 and 1790 when New York was still the United States Capital. Most of the pews have since been cleared away and placed in storage, with the exception of the ones that were used by Washington and Governor (and later Vice President) George Clinton. Before the pews were removed, however, they played another historic role: following the terrorist attack on the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001, the pews in St. Paul’s Chapel became a place for firefighters and rescue workers to rest and pray.

1. Old St. James Episcopal Church (1735)

Old St. James Episcopal Church was a mission church built in 1735 on a parcel of land granted by the town of Newton (later renamed Elmhurst). The Colonial church was built in the style of a meetinghouse, with a rectangular form, wood shingles, round-arched windows, and a timber frame. The parish erected a new, larger church in 1848, just one block North along Broadway. The old church was abandoned in 1849, although it was still used on special occasions. The second oldest religious building in New York City, it was granted landmark status in 2017.

The parish minister and most of the congregation at Old St. James Church remained loyal to England during the Revolutionary War. While the British army was encamped in Newtown Village, General William Howe, Prince William (later King William IV of England), and other high-ranking officers attended services at the church. After the war, the church broke ties with the Church of England and its parishioners proved their loyalty to America when they fought against the British in the War of 1812.

Next, check out 18 of NYC’s Former Military Forts and Inside the Stunning Restoration of Old First Reformed Church in Park Slope, Brooklyn!