100th Anniversary Great Nave Tour at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine

Celebrate the 1925 construction of the stunning nave inside the world's largest Gothic cathedral!

Guastavino Tile in the decommissioned City Hall Subway Station

Guastavino was once a name that was a household word amongst architects. The Guastavino Company, led by a father-son team of Spanish Immigrants, oversaw the construction of thousands of thin-tile vaults across the United States, including over 200 in New York City, between the 1880s and 1950s. From Grand Central Terminal‘s Oyster Bar and Whispering Gallery to the Municipal Building to the Queensborough Bridge, we walk amidst Gustavino’s tiles every day without noticing.

Opening today at the Museum of the City of New York is the exhibition “Palaces for the People: Guastavino and the Art of Structural Tile,” paying homage to the artisanal family.

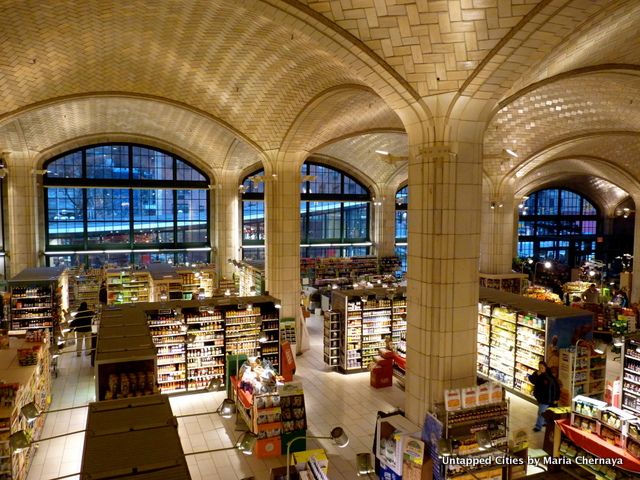

Queensborough Bridgemarket

The story of the Guastavino family and their long-standing architectural legacy in the United States begins in Valéncia. Rafael Guastavino Moreno was born in 1842, to a family of musical craftsmen. At the age of 19, he began studying at the Special School for Masters of Works in Barcelona. When he graduated, he received the title of “master builder,” rather than architect. This distinction in title meant that Guastavino’s training emphasized the hands-on aspects of building. Most importantly, his training in Barcelona introduced him to the ancient building techniques of Spain, such as tile vaulting, which has been in frequent use since the fifteenth century.

Municipal Building, Chambers Street

The earliest known origins of tile vaulting are in Valéncia. Unlike traditional stone vaulting, tile vaulting is built from multiple layers of thin bricks laid flat, which are set in place with fast-setting plaster, without the need for support from below. These features made tile vaulting revolutionary for being lightweight, low-maintenance, fireproof, and capable of supporting large loads.

Registry Room or Great Hall on Ellis Island

One of the earliest and most ambitious buildings that Guastavino designed during his career was the Batlló Factory, a major textile mill, in Catalonia. The building blended traditional tile vaulting with industrial innovations, and helped him earn prestige in Barcelona. In 1881, when Rafael Guastavino sailed to New York with his youngest son, Rafael Jr., he brought the tile vaulting technology he had mastered with him. The first American buildings he designed and constructed in New York City all used tile vaulting.

Whispering Gallery, one of the secrets of Grand Central Terminal

The United States did not have the same tradition of masonry vaulting as Europe. Prior to 1850, there were only about a dozen masonry-vaulted buildings in the United States. At the time when Guastavino arrived to the United States, there was a growing demand for fireproof construction. By transforming masonry vaulting into a modern, fireproof construction system, Guastavino was able to quickly gain recognition and an entry into the construction industry. With the help of a developer, Guastavino filed patents for his tile vaulting methods.

The Boston Public Library, designed by the firm McKim, Mead and White, marked Guastavino’s first major project in the United States. In 1889, Guastavino was commissioned to construct tile vaulting throughout the library. The success of the library allowed Guastavino to incorporate the Guastavino Fireproof Construction Company in July 1889. McKim, Mead and White’s confidence in the vaulting system impressed other architectural firms and led to dozens of commissions for the Guastavino Company.

Bronx Zoo’s Elephant House

One of the most extraordinary aspects of their patented vaulting techniques was that it exposed the tiles of the vaulting – a defining moment in the history of tile vaulting in America. By marketing a system that was both structural and decorative, the Guastivano Company pushed the boundaries of American architecture. The use of decorative tile vaulting was captured years later in projects such as the Della Robbia Room of the Vanderbilt Hotel in New York (now Wolfgang’s Steakhouse at Park Avenue) and the Nebraska State Capitol Building.

In its earlier years, the full potential of the Guastavino vaulting technology was realized in such monumental buildings as the Biltmore Estate in Asheville, North Carolina. In New York City, the Guastivano Company designed the vaulting in the City Hall Subway Station, the Queensboro Bridgemarket (now Food Emporium beneath the Queensboro Bridge), and St. Paul’s Chapel at Columbia University.

Cathedral of St. John the Divine

When Rafael Guastavino passed away in 1908, the company was taken over by his son Rafael Guastavino Jr. Under the leadership of the younger Guastavino, the company built a number of dome structures including the Elephant House of the Bronx Zoo, in New York City, and the National Museum of Natural History, in Washington D.C. One of the company’s most significant projects was the construction of the dome of the Cathedral of St. John the Divine (1909), in New York City. The dome, which measured 135 feet, was a miraculous feat in engineering, placing it among the world’s largest domes.

St. John the Divine’s Dome

By the time the Guastavino Company closed its doors in 1962, the originality of its soaring vaults helped shape the history of architecture in New York and the United States. The Guastavino legacy can be seen today in hundreds of buildings across the country, including the Oyster Bar in Grand Central Terminal, Carnegie Hall, the Municipal Building in New York, the Widener Library at Harvard University, Duke University Chapel, and the Ellis Island Registry Hall. Outside the U.S., Guastavino’s work influenced prominent architects such as Antoni Gaudi and Doménech I Montaner and continues to shape generations of architects in Spain, who visit Batlló Factory as a model of his work.

An exhibition on the work of the Guastavino Company is on display at the Museum of the City of New York from March 26 to September 7, 2014.

Reference: Ochsendorf, J. (2010). Guastavino Vaulting: The Art of Structural Tile. New York: Princeton Architectural Press.

Subscribe to our newsletter