Celebrate St. Patrick’s Day in NYC 2025

Discover 10 ways to celebrate St. Patrick's Day in NYC this year, from eye-opening tours to Irish treats!

While most are unlikely to stumble upon a car to take them to the 1920s, like in Midnight in Paris, Paris’s many museums offer a surprising number of portals to other places and times. Most of these are concentrated in the Musée des Arts Decoratifs, the Cité de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine and the Musée Carnavalet, though there’s also a surprising glimpse into the wilderness at the Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature… and Paris’s period rooms don’t just offer a tour of the past, but also an inquiry into the nature of display.

The Musée Carnavalet is home to some of Paris’s best known replicas and period rooms, though some almost always seem to be closed. This museum of Paris’s history was the first to reconstruct rooms once found elsewhere, with a group installed in 1878. They’ve since accumulated a collection of different places, and the museum prides itself on visitor immersion into the private, rather than public, lives of the past.

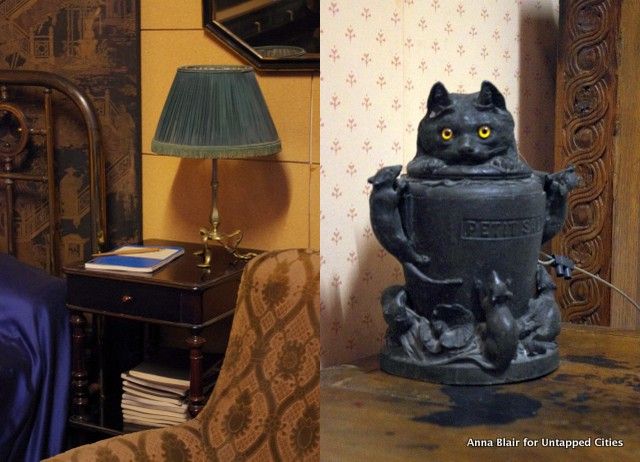

Nonetheless, the most interesting rooms are those associated with Parisian celebrities. Proust’s bedroom, like the nearby bedrooms of Anna de Noailles and Paul Léautaud, seems impossibly small for history’s most famous bedridden writer, but Paris was Paris even in the early twentieth century – and Proust, unlike many writers today, had other rooms beside the one in which he slept.

Unsurprisingly, given the parade of uninvited visitors with cameras past the roped-off cell, it doesn’t feel lived in, but the notebooks stacked on his bedstand add an aspect of the unassuming to a figure more associated with heavy volumes than pencil and paper. It’s these details, like Léautaud’s cat-shaped inkpot, that are most intriguing. The contents of all three bedrooms are the original belongings of their inhabitants.

The Musée Carnavalet’s most spectacular recreation might be Alphonse Mucha’s shop for Fouquet from 1901. Originally on the Rue Royale, it receives rather less foot-traffic tucked into a back corner of the museum’s first floor.

This is all the better for appreciating the sumptuous detailing, from patterned tiling on the floor to two peacocks, one perched near the roof while the other fans out behind the counter. It doesn’t feel real, though, with a sleepy guard hunched in a plastic chair instead of shop assistants opening cases for men in suits as one imagines in the early twentieth century.

The Cité de l’Architecture began life, before the Palais de Chaillot that now shelters it was constructed, as a cast gallery, so it’s not surprising to find it’s still crowded with replicas of buildings across France. While most of those acquired in the nineteenth century aren’t rooms but rather doors and sculpture from gothic cathedrals now spread across the ground floor, the more recent recreations of French architecture on the second floor are impressively immersive.

The most obvious is the two-storey replica of an apartment in Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation, which looks out across a sea of small models of twentieth century buildings. It seems striking that where Le Corbusier often figuratively dominates the century’s architectural discourse, one of his buildings now does so literally, with visitors often surveying the room from its balcony.

Those who’ve been inside Le Corbusier’s buildings around Paris will note this replica feels quite different to the Villa Savoye and his apartment in the 16th Arrondissement. It’s much darker, firstly. It’s hard to tell if this is because the bedrooms are so long and narrow, making it difficult for light to penetrate the centre of the building, or if it’s because of the unit’s placement within the museum, undoubtedly much darker than Marseilles, where the original was built. Unlike the rooms in the Musée Carnavalet, the original Unité d’Habitation is still standing and can be visited; it would be interesting to know how the replica compares.

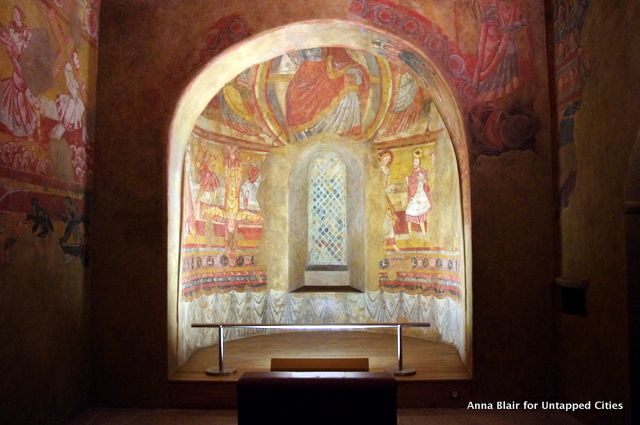

Nearby, but tucked away from the floor’s main room, is the Gallery of Mural Paintings and Windows, which focuses on copies from medieval churches. It’s a little like a rabbit warren, but one in which one stumbles upon empty chapels from the ninth century. There’s a magical quality to these spaces, secret caves that reward those museum visitors who take the time to find them.

The Musée des Arts Decoratifs has fewer replicas than the Musée Carnavalet and the Cité de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine, but seems more invested in exploring the ideas behind reconstructing period rooms in museums. The most interesting of the replicas here is Jeanne Lanvin‘s apartment, which visitors initially glimpse by putting their face up to windows and peering into the fashion designer’s bathroom, with its leopard skin toilet seats, and then her bedroom. One can only really enter the apartment’s entrance hall, where dolls peer from behind glass in a dark corner and the viewer’s own reflection bounces back from a central mirror. Here, the voyeuristic aspects of replicating a famous figure’s personal space are constantly in the visitor’s mind.

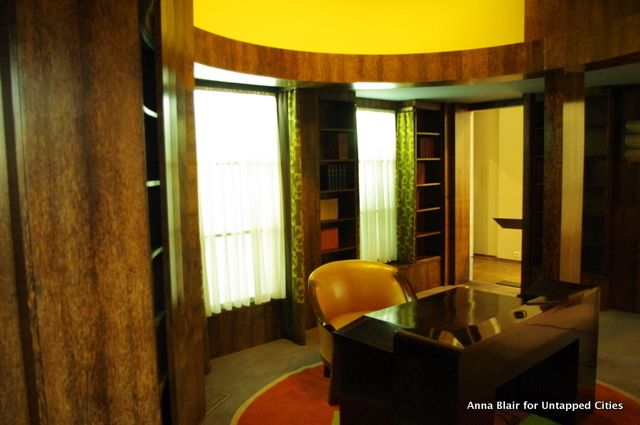

While almost certainly not a conscious decision, it’s a bit unfortunate that the female figure given the most space in the Musée des Arts Decoratif is represented by a boudoir, while men from the same period are linked with libraries (Pierre Chareau) and living rooms (Michel Roux-Spitz).

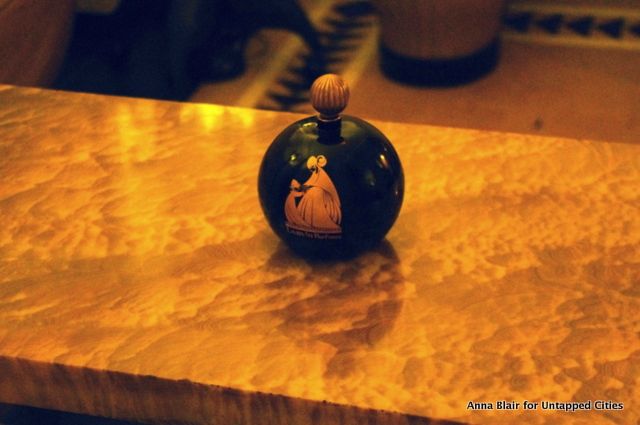

As at the Musée Carnavalet, there are replicas of hôtels particuliers from the eighteenth century. As with the twentieth century period rooms, it’s the details that suggest the way the rooms were lived in that are most exciting: a harp beside a chair conjures the image of somebody to play it just as Lanvin’s perfume bottle seems proof of connection between personality and place, imbuing reconstructions with the aura of inhabitants who, in fact, lived between different walls.

The Musée des Arts Decoratifs acknowledges some of these issues directly in Ceci n’est pas une Period Room, a postmodern take on the act of replicating spaces, with furnishings displayed on mirrored floors and cardboard cut-outs of famous figures. These items are, the museum notes, “linked only by our capacity to create an illusion”.

One last unusual replica can be found in the Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature, tucked in a back corner on the museum’s top floor (near a quirky display of gorillas sitting down to dinner beside models of the human digestive system that far outdoes ceci n’est pas une period room’s postmodern take on the construction of identities in museums). This replica is of Jacqueline and François Sommer’s hunting cabin at Belval in the Ardennes. Like the other replicas, hints of use are there in tins and personal souvenirs, but the Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature goes one step further in representing an inhabitant: here is a taxidermied badger, leaping onto a chair.

Taken together, all these period rooms in Paris museums—some empty and others crowded, some throwing the voyeuristic impulse back at visitors and others completely transportive—offer insights into just how much personalities manifest themselves in spaces, created or inhabited by particular people at particular points in history. It’s a reminder of how much Paris has changed, but also of how much the city is indebted to personalities.

Get in touch with the author @annakblair and check out her blog, Flappers with Suitcases.

Subscribe to our newsletter