100th Anniversary Great Nave Tour at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine

Celebrate the 1925 construction of the stunning nave inside the world's largest Gothic cathedral!

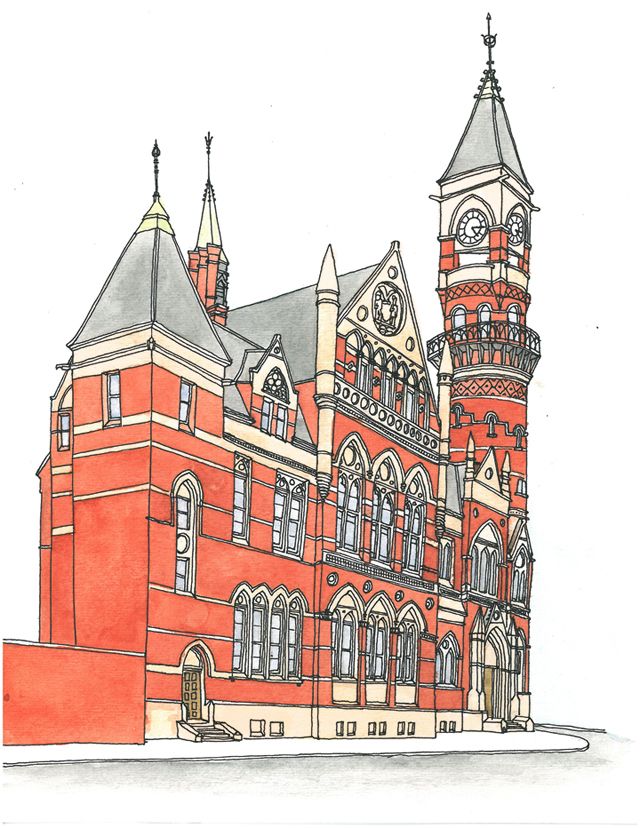

The Jefferson Market Library, formerly the Jefferson Market Courthouse has been a staple of Greenwich Village since 1874. After a heated battle to preserve it in 1967, this outstanding example of civic design still stands on its awkwardly shaped block formed by Sixth Avenue, Tenth Street and Greenwich Avenue.

The old block originally housed a dingy police court over a saloon, as well as a wooden fire tower. In 1870 the legislation in Albany decided to build a new municipal building on the site of the original market. By 1873, the plans for Jefferson Market Courthouse hit a bit of a snag. $150,000 had already been spent on materials that sat rotting a pile for years. A new set of supervisory commissioners evaluated the original scheme and determined that it would have cost several million dollars to build.

So they discarded the original plans and hired Fredrick Clarke Withers to draw up a new plan. Withers had helped the firm Vaux and Olmstead design Central Park after he emigrated to America from England in 1853. But the Jefferson Market building is Withers’ best known work. His design drew inspiration from William Burgess‘ competition for the London Law Courts and also from Venetian architecture. Withers designed an elaborate, tightly knit cluster of buildings that exploited the scenic potential of the acute angle at Sixth Avenue and West Tenth Street. This complex included a courthouse, the five story prison (demolished) and the fire and bell tower attached to the courthouse. There was also a market, which has since been demolished, that was designed by Hogan and Hogan in 1883. The complex was one of the country’s best planned urban renewal projects of its time.The total cost of the buildings, exclusive of architects’ fees, amounted to less than $360,000.The judicial building which housed the police and district courts was Withers’ masterpiece.

Its plan used every last inch of the unusual shaped lot to obtain the maximum accommodations. The one building was actually two triangular buildings wedged together into the acute angle of the lot with the fire tower hinging them together. 98 feet above the street sat the room for the look-out. It is reached by a separate, spiral stone staircase, with a private entrance from the street. On the first floor of the courthouse there were examination rooms, police court and offices for officers. The second floor had the civil court and rooms for judges. The third floor was reached by the staircase in the tower and had rooms for janitors and clerks. Connecting the courthouse and prison was an enclosed yard for the prisoners to be ushered in and out without publicity.

The entrance to the prison was on Tenth Street. Floor one had a guard room, a keeper room as well as two waiting rooms, one for male prisoners and one for female prisoners. Individual cells were provided on the second floor for 29 female prisoners and on the third floor for 58 male prisoners. A steam elevator moved the prisoners around the building and even up to an airing court on the roof for exercise without the change of escape.

Though the prison has since been demolished, the courthouse still stands. The basement is now a reference room not a kitchen. And the first floor has a children’s reading room and smaller room used as an auditorium. The spiral staircase leads to the main reading room on the second floor. There’s also a circulation desk, staff work areas and smaller reading areas. The third floor has a staff work room on one side that is connected to a staff lounge by a catwalk that spans across the main reading room below.

There is a stoop on the north facade that has an old iron railing that is possibly original. The nonstructural parts are opulently ornamented, especially the Sixth Avenue facade. The carving, which forms and important element of the design of the building, was done under the construction of William Simon. Carved details encrust the entrance and accumulate under the beautiful stained-glass windows and elsewhere around the building. The water fountain is decorated with reliefs depicting a weary traveller and a life-giving pelican. There is also a state seal in the main gable and a frieze representing the trial from Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice that hangs over the window above the main entrance.

The interior walls of the main halls and staircase are lined with stone. Doorways in the hallway on the first floor are limestone with square-headed openings faced with marble with ornamental arches over them. Original carved doorways and paneled doors throughout the building have since been painted black. Today a modern glass and metal vestibule surrounds the main entrance. A Partners in Preservation grant would enable the library to replace the main entrance doors.

Later additions and alterations include plumbing, partition alterations, fireproof doors and some ceiling height changes. In 1961 the clock in the tower was electrified as a result of efforts by Greenwich Village citizens. On August 23, 1961, it was announced the building would be rehabilitated by architect Giorgio Cavaglieri and used as a branch of the New York Public Library. Renovations started in 1965, the bricks were cleaned, new windows, doors and sashes were installed and a walk way connecting the two third floor rooms was constructed. New plumbing, heating and lighting also replaced the aging systems. On November 27, 1967, the building was formally opened as a library. To this day the New York Public Library calls the Jefferson Market building home. The building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1972 and was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1977, both under its name and as “Third Judicial District Courthouse”.

Click here to vote for the Jefferson Market Library, and find out more on Twitter and Facebook. Follow Untapped Cities on Twitter and Facebook. Get in touch with the author at @BMoke28.

Untapped Cities is an official blog ambassador for Partners in Preservation , a community-based initiative by American Express and the National Trust for Historic Preservation to raise awareness of the importance of historic places. For complete coverage, follow our Partners in Preservation category.

Subscribe to our newsletter