NYC Just Had Its Worst Year for Brush Fires this Decade

As brush fires continue to rage in the New York area, data shows that they’ve become more prevalent in recent years.

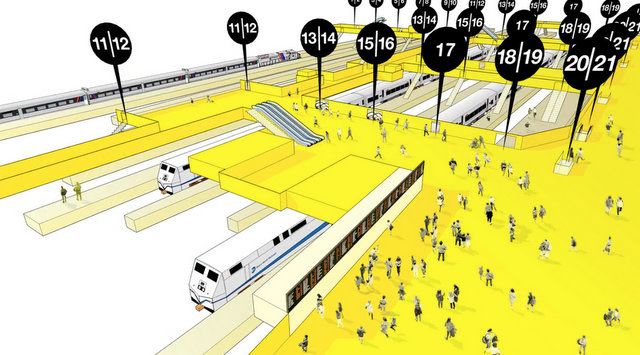

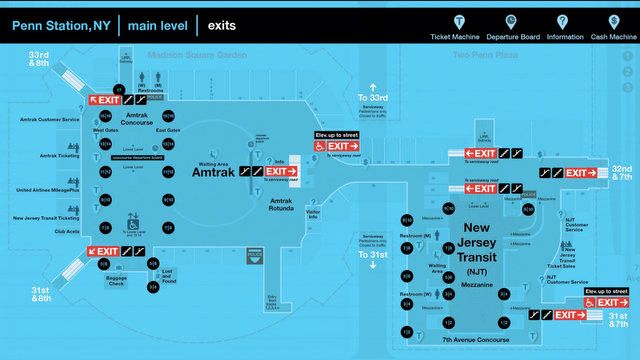

It’s no secret that Penn Station is really confusing. And there are very clear reasons for it. The labyrinth was birthed when the air rights were sold to Madison Square Garden, the original light-filled Pennsylvania Station was demolished, and everything pushed underground. Penn Station, home to four transit agencies, also has more people pass through it every day than the traffic at all three major New York City-area airports combined – about 600,000 people.

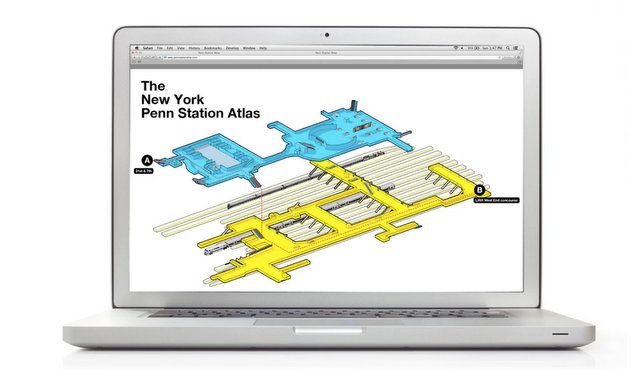

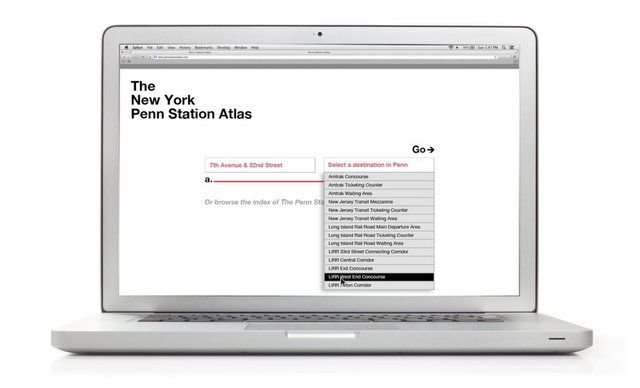

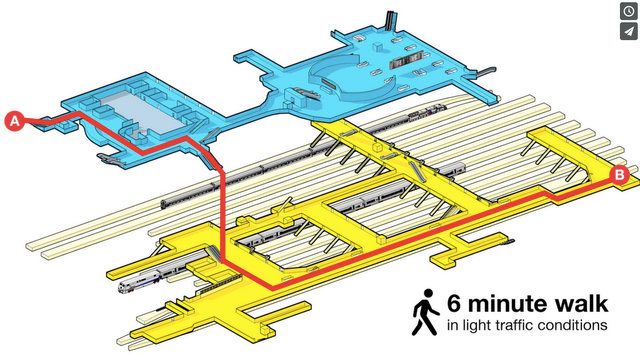

While most people complain about Penn Station, we’ve come to a new found appreciation for the much-maligned station after a year of hosting our monthly tour of the Remnants of the Original Penn Station. We’ve also discovered that others share a similar cautiously optimistic outlook. Designer John Schettino has one of the most comprehensive projects on the current Penn Station we’ve seen recently. When completed, the New York Penn Station Atlas will be a far more effective wayfinding device than simple two dimensional maps. Imagine if you it was easier to cut through the noise and find what you’re looking for?” Schettino asks in a video that also shows the potential cost of lost passengers in staff manpower in the station.

Schettino will combine 3D models and 2D diagrams, oriented to the traveler, using context to highlight relevant information. There will be “heads up maps” for orientation, access maps to show you what places look like, spotlight maps for filtering out key features, and 3D vistas. He’s already been discreetly documenting the station with notes, drawings and photos, taking inventory, and comparing them to existing schematics.

We asked Schettino a few questions about Penn Station about his project and Penn Station:

Untapped:What spurred you to create the New York Penn Station Atlas?

Schettino: In addition to being a designer I’m also a person who uses Penn Station on a frequent basis. Like many folks in Penn, I always use the station for one purpose. Prior to this project, I found that even though I used Penn regularly, because my trip was a repeating pattern, it was astonishingly easy to get lost whenever I departed from my usual path in the station.

And while the regular challenge of navigating Penn was part of the impetus for this project, I also saw Penn as an embodiment of a critical overlap of urbanism and mobility; two forces that are increasingly transforming everyday life. From that perspective, I conceived of The Penn Station Atlas as a way to apply my design abilities to a project that could have a positive impact on one small aspect of our shared urban experience

>Untapped: What are your next steps?

Schettino: Well, the project has definitely arrived at the point where it’s no longer sustainable as an independent initiative. The work that remains requires dialogues, testing, a budget and permissions for station access. These are all things that can only develop out of partnerships with agencies in Penn. Beginning with Amtrak, the landlord of the station, I’m aiming to meet with appropriate station administrators in order to present and discuss the project. Of course, I’m hopeful that getting the project in public, on sites like Untapped Cities, might help to bring it to the attention of people who have interest, or even influence, in the world of transportation, planning and urban design.

>Untapped: What’s your personal opinion on the station itself today?

Schettino: Penn Station is one of New York’s most deeply challenging and challenged public spaces. My own project focuses on a real but limited set of issues in the current version of Penn but the truth is that those things, and much of what frustrates users of the station, are only symptoms of the larger issue of underfunded public transit and the legacy of economic and cultural missteps behind the destruction of the original station.

Penn is the most used train station in the Western Hemisphere, handling more than twice its original planned capacity of two hundred thousand people per day. Functionally, the station is operating as a provisional solution. When you compound that circumstance with the question of Penn as a meaningful public space it’s not surprising that the station is so loathed by it’s users.

The good news is that The New York City Council recently put a limit on Madison Square Garden’s permit to operate on top of Penn Station and by 2023 MSG will have to relocate. This creates a singular opportunity to re-imagine Penn Station. The Alliance for a New Penn station, with their Penn 2023 report and public dialogue, has already done a lot of hard work to get that process started. I hope that city government and state and federal offices realize the urgency of the issue and are as forthcoming with funding for a new Penn as they have been with the new $20 billion Hudson rail tunnel, the Gateway project.

Untapped: What’s your favorite part of the station?

Schettino: My favorite part of the station is in the ambient audio environment of the Amtrak Concourse. That aural space is punctuated, at separate times, by the voices of two announcers, a man and a woman who call out train and station information. In my household, we refer to the female announcer as “The Voice of Penn Station.” And while her vocals are what specifically resonates for us, both of those invisible speakers embody a sense of order and a kind of dignity that’s a welcome counterpoint to the usual tone of the station.

Check out more at Penn Station Atlas. For a unique, historical exploration of New York Penn Station, join us on our next Remnants of Penn Station tour:

Tour of the Remnants of Penn Station

Subscribe to our newsletter