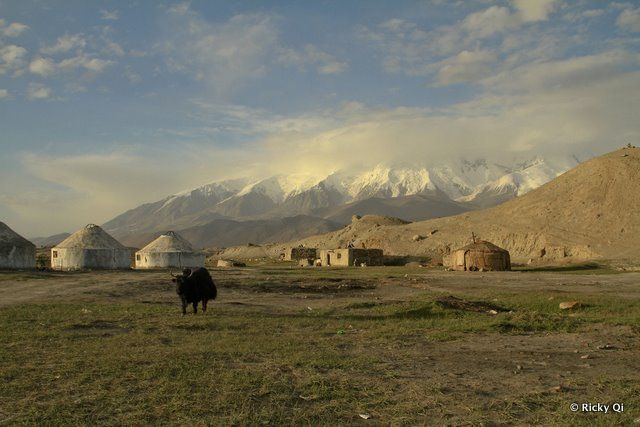

A stunning panorama view of an area the locals call the Shashan and Shahu, or Sandy Mountains and Sandy Lake.

When one thinks of China, often the first things that come to mind are pandas, kung fu, the Great Wall, mountains shrouded in mist, bamboo forests…bamboo forests covering mountains shrouded in mist…I digress. Recently the media’s portrayal of China’s rapid economic expansion has given the world a different set of images: sleepless megacities seemingly built up overnight, humanity bursting forth from every corner, an indistinguishable sea of faces that portray a seemingly unified front. This is the new century, the media tells us. This is China.

But a little known but important fact of the matter is that China’s landscape is still vast and relatively undeveloped, its peoples varied. Take Xinjiang, the rarely mentioned frontierland in China’s northwest; so little of this place resembles what we have collectively come to know as China. Boasting a size nearly four times that of California, Xinjiang (which means “new frontier” in Chinese) is home to an eclectic mix of races: Uyghur, Mongol, Kazakh, Hui, Kyrgyz and now more than ever Han Chinese.

For centuries, Xinjiang was a place far removed from civilized Chinese society. It was a mysterious land occupied by a number of nomadic peoples, a place of exile for imperial officials and a refuge for criminals wishing to remain incognito. But perhaps Xinjiang’s biggest claim to fame was its role in the legendary Silk Road. For centuries, the town of Kashgar, a small western oasis, sat as the gateway to the Far East. Tucked between the Taklamakan Desert and a literal maze of mountain ranges leading to Pakistan, Tibet and subsequently the Himalayas, Kashgar served as an important stop for weary traders trudging along this particularly treacherous path of the Silk Road. In August of 2010, I had the privilege of traveling to Kashgar and traversing up the Karakoram Highway, the highest paved road in the world, toward the borderland between China and Pakistan. The people I met and the landscapes I saw opened my eyes to the true vastness of China. Far away from the neon lights and shopping districts of Beijing and Shanghai, along a sparsely populated mountain route, I had found something that will forever shape my idea of what and whom China is.

One of two minarets of the Id Kah Mosque, the central point of religious activities in Kashgar.

The dominant religion among Uyghurs is Islam.

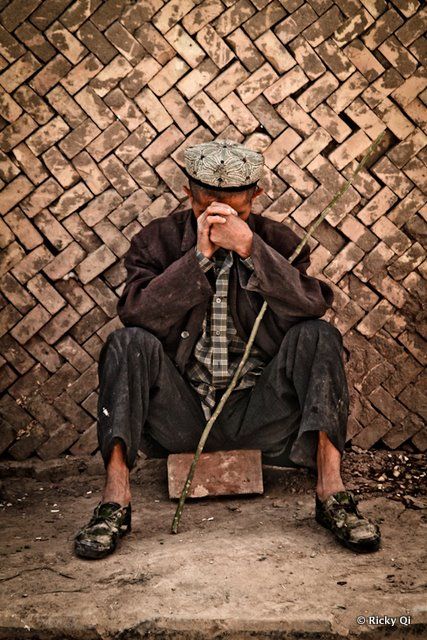

An Uyghur man sits in resigned contemplation. Uyghurs have called Xinjiang their home for thousands of years, but increased migration of Han Chinese has made life here increasingly complex, with racial tensions reaching a boiling point in the riots of 2009.

CCTV Police Cameras and armed Chinese SWAT (not pictured) watch over a community of Uyghurs observing afternoon prayertime in the Erdaoqiao area of Urumqi, the focal point of the riots.

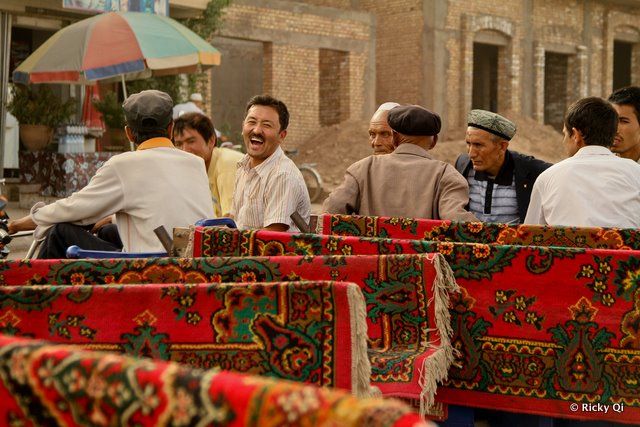

Kashgar, old district. A man laughs as his picture is taken.

Kashgar, old district. A man laughs as his picture is taken.

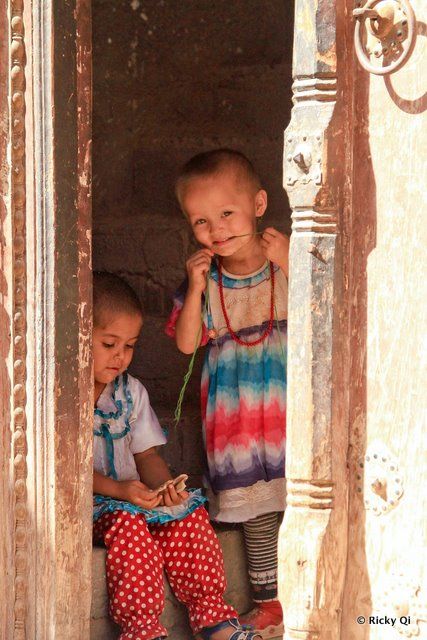

Two Uyghur girls peek outside of their house in the old district of Kashgar. Some Uyghurs shave the heads of babies, a pre-Islamic shamanistic practice to scare away baby-stealing spirits.

Two Uyghur girls peek outside of their house in the old district of Kashgar. Some Uyghurs shave the heads of babies, a pre-Islamic shamanistic practice to scare away baby-stealing spirits.

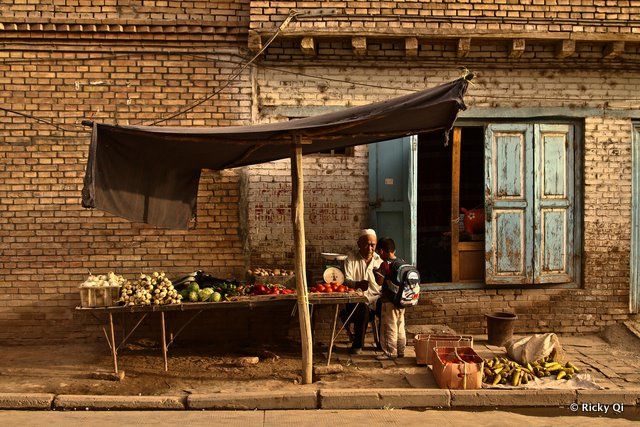

A quiet moment between a fruit vendor and his grandson. Fruits, especially melons from Xinjiang, are widely known throughout China. The Chinese term for honeydew (Hami Gua) derives its eponymous name from the oasis town of Hami.

A quiet moment between a fruit vendor and his grandson. Fruits, especially melons from Xinjiang, are widely known throughout China. The Chinese term for honeydew (Hami Gua) derives its eponymous name from the oasis town of Hami.

Much of Kashgar’s old town is being razed in order to make way for new land developments. Kashgar was recently named a Special Economic Zone by the central Chinese government, which has led to much needed funds funneling into the area. Here, two men continue their fruit vending business in the old district of Kashgar, which may very well be gone within the year.

Much of Kashgar’s old town is being razed in order to make way for new land developments. Kashgar was recently named a Special Economic Zone by the central Chinese government, which has led to much needed funds funneling into the area. Here, two men continue their fruit vending business in the old district of Kashgar, which may very well be gone within the year.

The Sunday animal bazaar in Kashgar draws farmers, shepherds and spectators alike. Here two men shear their livestock.

The Sunday animal bazaar in Kashgar draws farmers, shepherds and spectators alike. Here two men shear their livestock.

Sheep lined up for potential customers and curious camera-toting tourists.

Sheep lined up for potential customers and curious camera-toting tourists.

The view (1) at 6am outside of Kashgar along the Karakoram Highway.

The view (1) at 6am outside of Kashgar along the Karakoram Highway.

The view (2) at 6am outside of Kashgar along the Karakoram Highway.

The view (2) at 6am outside of Kashgar along the Karakoram Highway.

Wild camels roaming the desert landscape along the highway, two hours outside of Kashgar. The signature red earth of the canyons in the Gez River Pass display their full splendor at sunset, turning the landscape fire red.

Wild camels roaming the desert landscape along the highway, two hours outside of Kashgar. The signature red earth of the canyons in the Gez River Pass display their full splendor at sunset, turning the landscape fire red.

As one ascends the Karakoram Highway, deserts make way for imposing mountains. This is the area where the Tianshan, Hindu-Kush and Himalayan mountain ranges begin to converge.

As one ascends the Karakoram Highway, deserts make way for imposing mountains. This is the area where the Tianshan, Hindu-Kush and Himalayan mountain ranges begin to converge.

A stunning panorama view (2) of an area the locals call the Shashan and Shahu, or Sandy Mountains and Sandy Lake.

A stunning panorama view (2) of an area the locals call the Shashan and Shahu, or Sandy Mountains and Sandy Lake.

The turquoise waters of Lake Karakul are a welcome sight for weary travelers. Two Kyrgyz settlements dot the shores of the lake, and for a small fee they are willing to house travelers in their own homes for the night.

The turquoise waters of Lake Karakul are a welcome sight for weary travelers. Two Kyrgyz settlements dot the shores of the lake, and for a small fee they are willing to house travelers in their own homes for the night.

The eternally snowcapped Mt. Muztagh Ata, 43rd highest mountain in the world, watching over the lake.

The eternally snowcapped Mt. Muztagh Ata, 43rd highest mountain in the world, watching over the lake.