Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

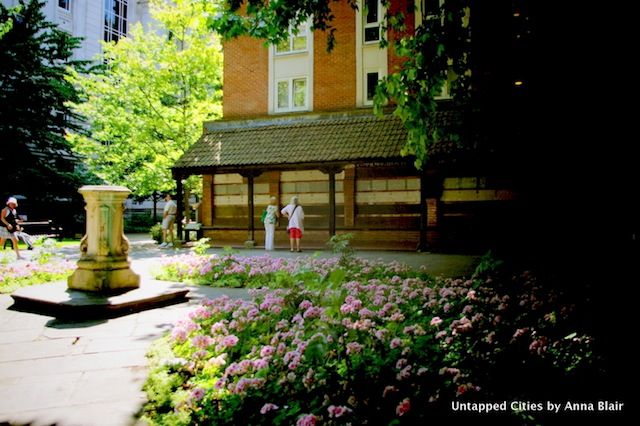

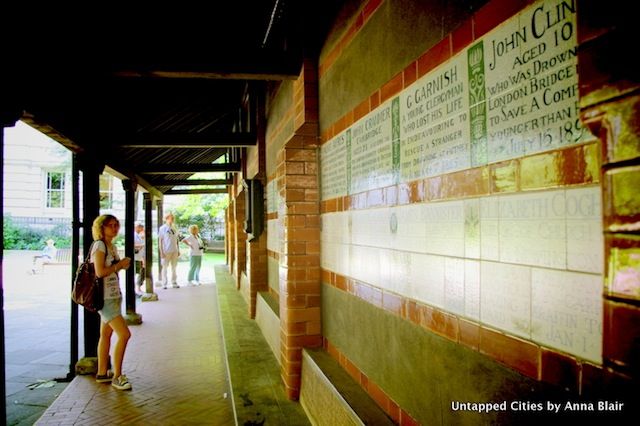

The City of London has many idylls tucked amongst its glass buildings and clogged thoroughfares, empty on weekends and filled with businesspeople eating most lunchtimes. Postman’s Park is among the most interesting of the city’s small parks, dominated by a wall of tiles commemorating acts of heroic self-sacrifice.

Postman’s Park, named for its location beside London’s former General Post Office, now a hotel, dates from 1880. It has an unusual shape, long and sometimes narrow, sometimes wide, both boxy and sinuous. This shape springs from the park’s origins, composed of the churchyards for St. Leonard’s Foster Lane, St. Botolph Aldersgate and the Christchurch graveyard. The space’s former use as a graveyard is not disguised, with graves gathered together against the buildings at the sides of Postman’s Park; the land, too, is elevated above the surrounding streets due to older burial practices.

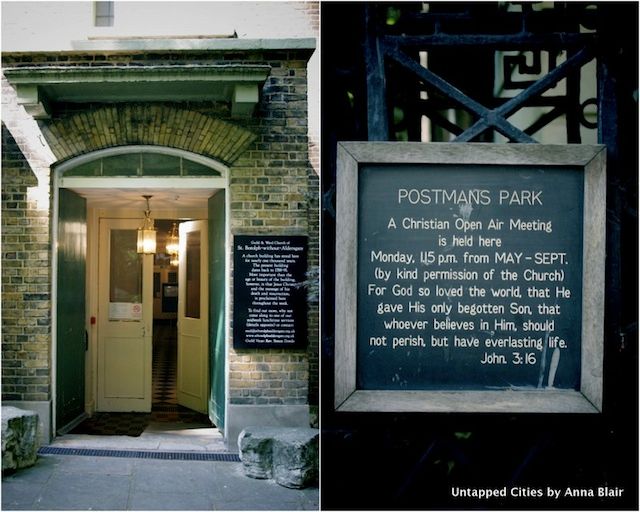

Postman’s Park retains some functions as a churchyard. The entrance to St. Botolph Aldersgate is located inside the park, and religious gatherings are held outdoors in summer. This is also the only church in London to hold services on a Tuesday rather than a Sunday, in recognition that those who work in the parish are unlikely to be in the City on the weekends.

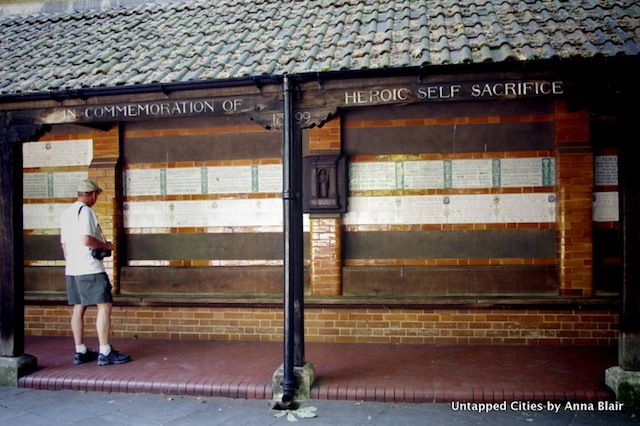

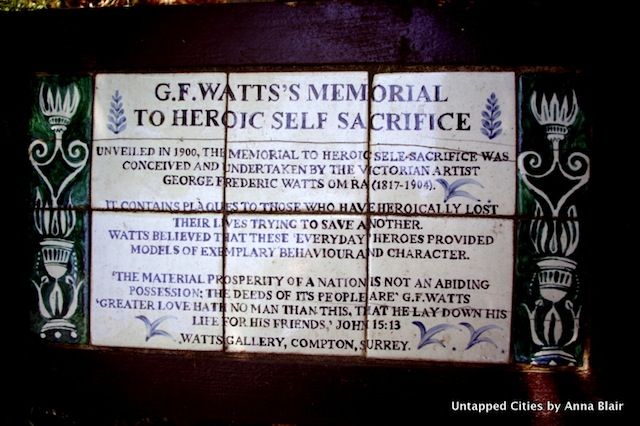

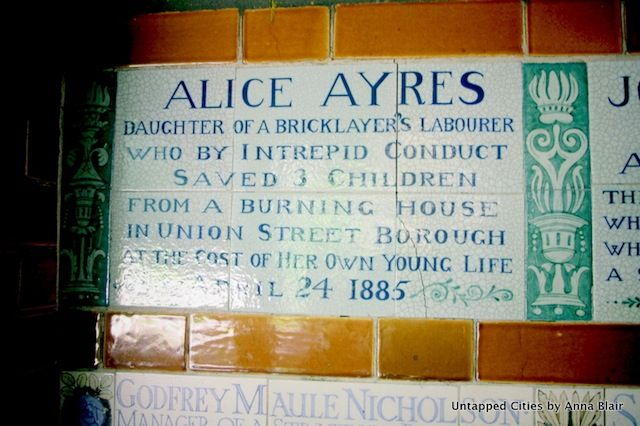

While St. Botolph’s can trace its history back to 1493, Postman’s Park is best known for its loggia of tiled memorials to heroic self-sacrifice, proposed by George Frederick Watts. Watts, an artist best known for Hope, an allegorical painting now in the Tate Britain, had long been interested in celebrating the bravery of ordinary people. He suggested, in a letter to The Times published in 1887, that to build a monument to selfless acts in Hyde Park would be an excellent way to mark Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee year.

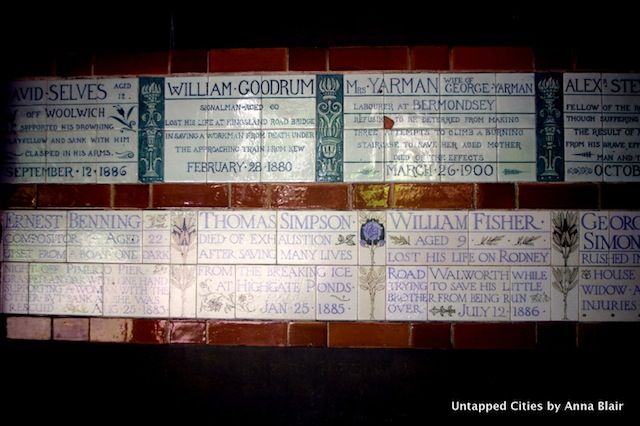

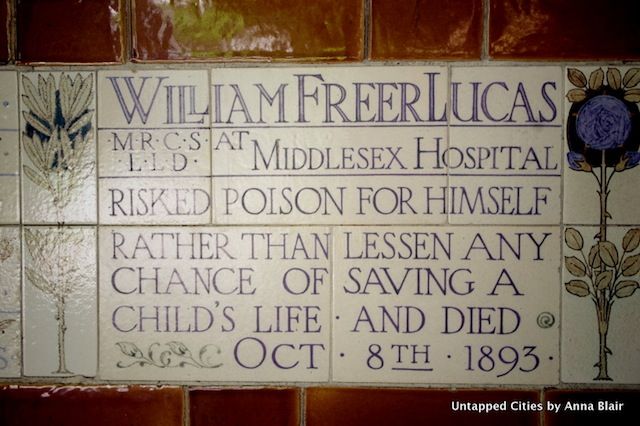

This initial proposal was unsuccessful, but in 1898 Postman’s Park was suggested as an alternate site for the memorial, the idea of which Watts had continued to promote. The Memorial to Heroic Self Sacrifice was opened in 1900. It takes the form of a long loggia sheltering a wall of glazed ceramic tiles. The first of these, still in place, were green and white, designed by Willem de Morgan. Watts died in 1904, but his wife, Mary Watts, ensured the continuation of the memorial.

In 1905, in a gesture that would have angered G. F. Watts were he alive to note it, a wooden memorial to Watts himself was installed amongst the plaques. The wooden figure of Watts, holding a scroll marked ‘heroes,’ stands at the centre of the loggia. There is now also a large tile explaining the genealogy of the project, again emphasising Watts’s idea over the individual acts he wished to see honoured.

Nonetheless, it is these acts which touch the visitor to Postman’s Park; the stories detailed on these tiles humanise names that are sometimes over a century old. They impress upon readers the lasting merit of selflessness, perhaps particularly important in the City of London, where short-term corporate profit is more often an aim. Visitors at the Memorial to Heroic Self Sacrifice tend to linger and think about the inscriptions. Postman’s Park, with its shady tiles, goldfish pond and flowers, feels far away from the glass buildings and rush of crowds more usually associated with this area.

Mary Watts and the Heroic Self Sacrifice Memorial Committee continued to add tiles to the wall, though more sporadically following the closure of Willem de Morgan’s ceramics business in 1907; Royal Doulton’s designs, which now dominate the wall, were less appealing. When Mary Watts died in 1934, her husband–and Victorian ideals–had fallen out of fashion, and so Postman’s Park received little attention.

This changed with 2004’s Closer, with which Postman’s Park is now often associated. Significant moments at both the film’s opening and close occur at the Memorial to Acts of Heroic Self Sacrifice. The tile dedicated to Alice Ayres is central to the film’s action; Ayres was, after saving three children in a fire in 1885, seen as a secular saint, and it was her example that Watts invoked when first suggesting the memorial. Postman’s Park acts as a symbolic force in a film exploring the selfish cruelty of contemporary humanity, and it seems Closer has succeeded in introducing our century to this small corner of Victorian London. There are now always a few tourists in Postman’s Park, and another tile was added in 2009, the first in 78 years.

Get in touch with the author @annakblair and check out her blog Flappers with Suitcases.

Subscribe to our newsletter