NYC's Long-Awaited Davis Center Opens in Central Park

A stunning new facility at Harlem Meer opens to the public this weekend!

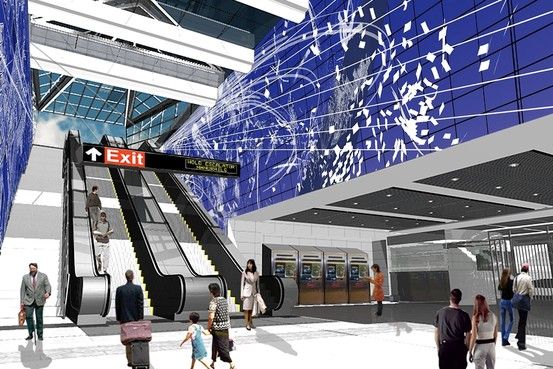

Sol LeWitt, Whirls and twirls (MTA), 2009. 59th Street-Columbus Circle station.

Sol LeWitt, Whirls and twirls (MTA), 2009. 59th Street-Columbus Circle station.

Sandra Bloodworth has been the Director of the Metropolitan Transit Authority’s Arts for Transit program since 1996. She graciously sat down with me to talk about Arts for Transit’s role and mission, and the particular opportunities and challenges that accompany the commissioning and installation of long-term, durable public artwork throughout the veins of New York City: the subway system.

Could you talk about how the context for Arts for Transit has changed in the twenty-seven years you’ve been here?

Well, initially, when Arts for Transit was founded and we were a fledgling organization, we learned a great deal. We learned things that worked and things that didn’t work. By the mid-‘90s we had established our policy and procedures, and we were pretty much the core of who we are, and how we do business, by then. We had learned a great deal from others and from looking at ourselves and at our environment. Now, over the years we’ve refined it: it’s a living, organic process and a lot is very unique. There have been some subtle changes, but it’s become pretty much the standard around the country.

Of course it has! I read the interview you did with UrbanOmnibus and I was surprised to learn that Arts for Transit isn’t just responsible for visual and performing arts. You said that the program acts as an advocate for good design within the MTA.

Yes, we are an advocate for good design. Sometimes we have the good fortune to be very involved in design projects such as the vending machines.

Which were in a MoMA exhibition last year!

Yes, they were in Talk to Me. And we also are involved with the trains, from time to time, and we were very instrumental in the water mitigation project. We serve in many ways as a consultant and help with the administrative side””wherever we can be helpful to the agency. We are so pleased that the agency has emphasized good design on these industrial projects.

Were you involved at all in the “Help Point” intercoms, which are right now on view at MoMA in the Architecture and Design galleries?

Yes, we were involved. And they are in MoMA’s permanent collection.

What do you see as public art, as opposed to, maybe, “museum art? What are the specific problems, limitations, and opportunities of public art?

Well, the first thing is that whereas the impetus for much of the art you see in museums was the artist’s vision and the work was often created in an intimate setting, public art is just what it says””public. It is created for the audience that sees it. Our goal is to understand who our audience is, and we knew from the beginning that our audience is our riders. Now, in New York that’s quite a diverse group. Then, that’s coupled with the goal of creating the best possible art that we can. The emphasis is always on high quality art.

When I was doing my explorations of subway art I noticed that a lot of pieces appear to be directly referring to the communities and neighborhoods they’re in; it seemed like something that a lot of the artists were explicitly trying to do.

Yes, that’s true. But sometimes it may be subtle. The Sol LeWitt captures the energy of its location””LeWitt’s body of work interacts with that space and that place. But we always work to have the community be involved and have input on the process. The artwork is selected by arts professionals, yet very often they will have a geographical connection to the community. They may be a curator in a museum in that community””you know, in New York you don’t have to look but a few feet to find a very qualified arts professional. We’re blessed in that resource here. We ground the art so it’s specific to the place it’s in and to the riders, but it’s up to the artist how to interpret that: sometimes it’s very little and sometimes it’s not. But you will see that connection all the way through. That is what ties all these works together: that they are about where they are.

And then at the same time, New York is a city of tourism. I did notice there are more projects along 42nd street, for example, and downtown””there’s a great piece at Coney Island, a great piece at Yankee Stadium, these hot spots””whereas there are less pieces the further out you go into the boroughs.

That’s not really true. I mean, to some degree that might be true. We commission art wherever there’s a rebuilding project. Initially, many years ago when we started out, for the first five years there was a matrix: they had done a survey of all the stations and the worst stations—most-used, the highest numbers, worst condition—came first. Of course, some of the worst stations are going to be in midtown, they are going to be terminal stations like Stillwell Av with Coney Island recreation area and Flushing-Main St, where you have large numbers of people entering and exiting. So to some degree what you said is true, but now we have done so many projects. I mean, we were doing 19 projects in the Bronx at once.

So projects are generated when a station is already under construction?

Yes, we’re not determining stations. There are different processes by which they get selected, which is a much more complicated thing.

Then right now you are working on the Second Avenue Subway? I‘ve seen a couple graphic drawings released.

We are! We’re working with Chuck Close, with Jean Shin, and with Sarah Sze.

Proposal by Jean Shin for the Second Avenue subway 63rd Street Station.

Proposal by Jean Shin for the Second Avenue subway 63rd Street Station.

A rendering of the Second Ave subway 96th Street station with art by Sarah Sze.

A rendering of the Second Ave subway 96th Street station with art by Sarah Sze.

These works have to deal with conditions that would drive any conservator nuts: the heat, the humidity, some of them the outdoor weather, and, unfortunately sometimes human vandalism.

I think one of the true successes of this program is that we knew from the beginning that our ability to maintain would be very limited, and so we worked with durable materials. But in those early days we looked at where we are: we’re in the middle of subway stations with miles and miles of walls. At that point we were 80 years old, and now we’re much older—108 years old. So we looked to what had lasted and, if there’d been no intervention by humans or nature, mosaics last. They last for thousands of years in perfect condition! So, knowing we would have very minimal ability to clean them, and simply from an aesthetic point of view, mosaics made sense. At the time the mosaic industry in the United States was somewhat limited. Between our program and the architectural mosaics and then public art programs across the country the industry has been revived and is thriving.

But we don’t just do mosaics, that was to start. We looked at other materials that hold up: bronze; glass in certain conditions—faceted glass, durable glass; and now we’re using a lot of cut metal, like the railings at South Ferry: they’re very hardy. Our goal is always to be as durable as possible.

Doug and Mike Starn, See it split, see it change, 2008. South Ferry station.

Doug and Mike Starn, See it split, see it change, 2008. South Ferry station.

Doug and Mike Starn, See it split, see it change, 2008. South Ferry station.

Doug and Mike Starn, See it split, see it change, 2008. South Ferry station.

We work with the station departments on cleaning and conservation; this tiny little staff monitors all the art. The collection is now over 25 years old— couple works are 27 years old—and it has to have some maintenance. We divide the 230 works among 4-5 people and each person has a year to go inspect everything. We have a condition report on every piece and we locate projects that need attention and we do what we can every year to repair those most needed. And then the stations department will call us if there’s a problem and we will work together to repair it. It’s a slow process. But as we repair we try to figure out, “How can we do this now that will not have the same repair again?”

I know that New Yorkers feel very strongly about all aspects of transportation—when “Poetry in Motion” was temporarily ceased people had extreme opinions about it. What is the community response like when you put a piece into a local station?

I think that’s been the most rewarding part of this program: from the beginning the public knew that we were doing this because we were focusing on the audience. They knew it was for them. And they own it, it’s theirs””it’s the public collection. Randy Kennedy called it the most underrated art museum in New York. Made my day! People get that. They have preferences, but overall they love that this is here. Art is a small part of these renovation projects, but it has a huge impact because it is what you see. It is integral to creating a vibrant transportation environment. This is particularly true in these hundred-year-old stations, but it’s equally true on these new projects that we’re building, that very often the art integrates with the architecture to create a place that just seems so right.

I know that the Sophie Blackall illustrations have proven very popular””I saw them all over the internet, and in one instance someone even tried to steal one!

We were approached by the Car Equipment department when we were working on the trains. The inside of the in-route destination became a big palette””and there was great concern that it would not be a palette of what we wanted””so we created a space on those particular trains, the R142s and it’s been extremely successful. It’s really engaged the public: it’s the art that’s on the train. Yes, the Sophie Blackall has been so popular. There’s a video online of how she creates the piece, and she’s on the train capturing the train, capturing the people and adding her own sense of humor and style and design and it completely captivates people.

It may be like naming a favorite child, but is there any piece that either is important to you for a specific reason or was important within your career or was significant for the program?

You answered it right up front. Every project is unique to its situation. Were there special opportunities we had, moments that changed this program? When Elizabeth Murray did 59th and Bloomingdale’s. Elizabeth not only decided to do a project in the New York subway—she was selected like everyone else—but she wanted it to have a tremendous impact. Beyond the fact that it was her, a major artist of the 20th-21st centuries, she did a project that was further than what people could imagine at that point. Since then we‘ve done some very large projects: Roy Lichtenstein did a very large project, but his was much later. Elizabeth was the one that went in first and then all of a sudden not just other artists but people stood up and took notice: “Let’s look at this collection. Who’s down here!?”

Elizabeth Murray, Blooming, 1996. Lexington Avenue-59th Street station.

Elizabeth Murray, Blooming, 1996. Lexington Avenue-59th Street station.

Elizabeth Murray, Blooming, 1996. Lexington Avenue-59th Street station.

Elizabeth Murray, Blooming, 1996. Lexington Avenue-59th Street station.

Our work is to speak to our ridership and that drives us. The collection is a mix of emerging artists, mid-career artists, and extremely well-known artists. Some of the artists that are well known weren’t well known when their project was done. Some works speak very specially to their community; some works speak more to the larger community. And that’s a wonderful mix.

The interview took place on 14 September 2012. This is an edited transcript.

Get in touch with the author at @kaygegay.

Subscribe to our newsletter