Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

Recently, each state has been meticulously deciding whether or not to open schools in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic. In New York, Governor Andrew M. Cuomo and New York City mayor Bill de Blasio have discussed a blended learning model in which students are taught on-site in school for certain days and remote on other days. In order to protect its 1.1 million students, New York City will distribute 300,000 iPads to students in need and will frequently update curricula to accommodate this transition to online learning. Mayor de Blasio announced that the city was working to provide child care to 100,000 students in libraries, community centers and other locations on days they are learning remotely.

Yet, many parents and teachers have been calling for open-air learning, which according to a Daily News op-ed “offers children authentic, stimulating experiences that foster skills like creative problem solving, independence, flexibility and resiliency as they form a deep connection to the natural world.” As coronavirus is at its greatest risk indoors, many New Yorkers have been pushing for an outdoor component to education, utilizing New York City’s 28,000 acres of public parkland. This system of outdoor learning is not new whatsoever, as schools incorporated outdoor elements in New York during the early 1900s.

Open air school in New York City. Photo from George Grantham Bain Collection in Library of Congress.

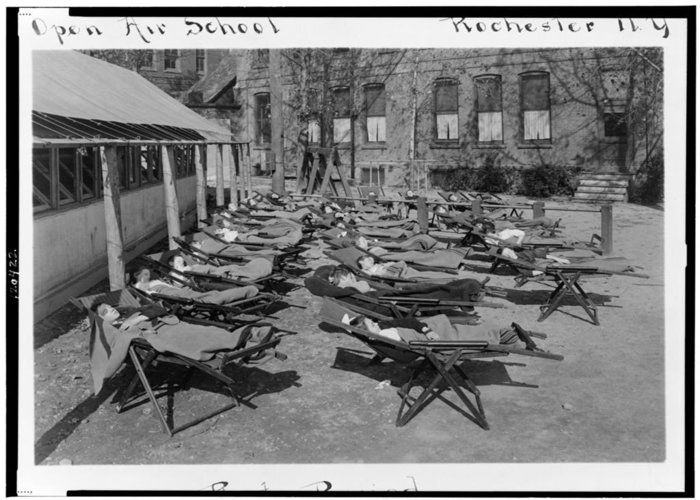

The open-air school movement occurred in the early 1900s particularly in the United States, England, and Germany. In 1904, German doctors opened the Waldschule für kränkliche Kinder, or forest school for sickly children, in the area of Charlottenburg for children with pre-tuberculosis. Similar schools were opened in the first decade of the 20th century in Belgium, Switzerland, Italy, and France, as well as a number in London. An experimental school set up in Rhode Island in 1908 was largely successful, as no children got sick even in the cold winter. Children stayed warm in wearable blankets called “Eskimo sitting bags,” and within two years there were 65 open-air schools around the country.

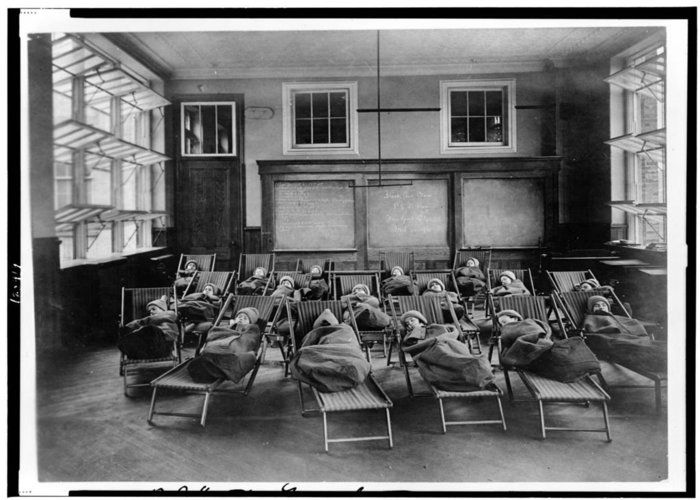

Children sleep at an open-air public school in New York / Library of Congress

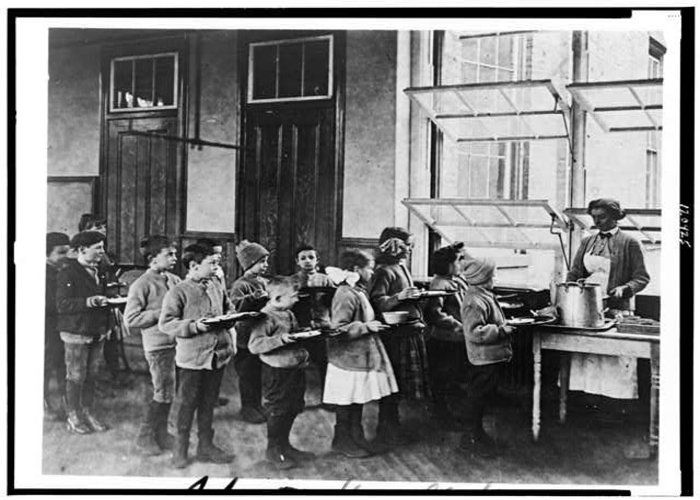

One of the first open-air schools in New York City was Public School 51, which featured wide-open windows to keep fresh air flowing into the building. In one image, young children sleep in their sitting bags on beach chairs in front of a blackboard, while in another, children line up for lunch while wearing heavy coats. Public School 33 was another open-air school, as well as one at Carmine Street above a public baths building. Another city school even had classes on an abandoned ferry, equipped with desks, a chalkboard, and plenty of chairs. At the time, it was believed that exposure to fresh air and light could combat tuberculosis.

Children line up for lunch at a public school in New York City / Library of Congress

This theory also held true at the Horace Mann School, which built two open-air spaces on the rooftop. According to a 1914 report, “The children who make up the classes were chosen because they were nervous, or irritable, or anaemic, or undernourished. There are at present two open-air classrooms, one having 8 second-grade and 16 third-grade pupils, the other being made up of 15 fourth-grade children… The open-air rooms are of concrete and steel structure, the walls being concrete. Each room is closed on three sides only, the south side being entirely open with a drop curtain to close that side in time of storm… There are windows in the upper half of the north side of each room which may be opened or kept shut according to the weather; there are also a few such windows in the east and west walls, besides skylights in the ceilings.”

Children sleep outdoors at a Rochester open-air school / Library of Congress

Open-air schools in New York came under criticism when doctors and medical directors remarked that poor weather and increased building expenses did little to help ill children. Yet others, including the New York City health commissioner in 1929, endorsed open-air schools, citing Chicago doctor Benjamin Goldberg to advocate that “more attention be paid to the pupil’s health than the maximum seating capacity.”

Open air class in manual training on the boat SOUTHFIELD at Bellevue Hospital, New York City. Photo by Jessie Tarbox Beals from Library of Congress. Bellevue Hospital transformed ferry barges into floating wards to battle tuberculosis.

Although many of these open air schools had died out by the next few decades, a number of schools in the city incorporated nature into their curricula, from urban nature preschools to schools that tended to local gardens. A 2018 study conducted over an academic year found that fifth graders participating in an outdoor science class showed increased attention over those in a control group, further supporting the move towards outdoor learning.

Many organizations in New York City provide opportunities for outdoor modules to school children, like the Edible Academy at the New York Botanical Garden and the Billion Oyster Project’s Harbor School on Governors Island. Some New Yorkers have been advocating for all kindergarten, first- and second-grade classes to be held outside, while others have looked towards a schedule for all students to receive both indoor and outdoor learning while reducing the number of students in school buildings.

The Edible Academy at the New York Botanical Garden

Many parents agree with the analysis of Dr. Goldberg nearly a century ago, while others want to open up schools as quickly as possible. Regardless, this option of open-air learning has proven successful for decades and may be a promising option for city schools this fall.

Next, check 10 of the oldest schools in NYC. And discover NYC’s Lost Historic Amusement Parks!

Subscribe to our newsletter