Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

We recently took a Municipal Art Society tour of Queensbridge, America’s largest operating public housing project, located in West Queens. The Queensbridge Housing Development is one of the 330 developments owned by NYCHA. Queensbridge is divided into two separate complexes – the North Houses on 40th Avenue and the South Houses on 41st Avenue – that together house over 6,000 people in approximately 3,000 apartments. Each of the 29 apartment buildings holds 96 units. You might be surprised to learn that the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) is the biggest landlord in the city: NYCHA owns 178,000 apartments and houses about 5% of the NYC population.

In popular culture, Queensbridge was the childhood home of notable rappers like Nas, Mobb Deep, Marley Mal, Blaq Poet and Roxanne Shante; as well as of NBA player Ron Artest (currently known as Meta World Peace) who plays for the Los Angeles Lakers. Nas, who lived on 40th Avenue, referenced Queensbridge in “One Love” and other songs:

So I comes back home, nobody’s out but Shorty Doo-Wop

Rollin’ two phillies together in the Bridge we called ’em “oo-wops”

— From “One Love” by Nas

Queensbridge has seen its share of violence and crime like other large public housing projects beginning in the 1950s, when government policies acted to separate middle from low income residents in housing sites. Prior to the 1950s, NYCHA and New York City had been virtually the only places in the United States where projects were not segregated. Beginning in the 1960s, Queensbridge had completed the transition into a predominantly low-income housing project. By the 1980s and 90s, Queesnbridge turned into a major site for drug dealing and crime; and had the distinct notoriety for having the most murders in 1986 of any project in New York CIty. In 2005, Queensbridge made news after authorities raided the housing project to dismantle the infamous “Dream Team” drug syndicate.

In Queensbridge, the building appearance and structures are similar to other federal public housing projects. Queensbridge opened in 1939 and its buildings sacrificed interior space, minimalized design to an unremarkable grayish brown color, and operated elevators that only stopped on the 1st, 3rd and 5th floors; all in an effort to reduce cost. Today, the elevators still skip the 6th floor.

On the other hand, Queensbridge is distinct in several ways: its buildings are uniquely shaped as two Y’s connecting at the base, in an effort to give residents more access to sunlight than traditional cross-shaped buildings. While the designers sacrificed interior space to reduce cost, they invested in exterior amenities. Our MAS tour guide referred to Queensbridge as a “public neighborhood,” both due to its population size and to the wide range of community activities taking place in its public spaces.

Queensbridge Park at the West end of the projects has views of the East River and Queensboro Bridge in addition to green space and athletic grounds.

By the mid-2000s, Queensbridge was fighting its way back to better safety and upkeep. Today, the public spaces around the complex aim to better sustain community life. The exterior amenities include tree plantings, playgrounds, green spaces, libraries, community centers, and a central commercial space. The multi-use plan was purposefully developed by NYCHA to provide revenue for the project in addition to giving residents access to basic products and services.

Associated Market, the grocery store in the middle of Queensbridge.

The brand-new health clinic opened its doors in the center of Queensbridge to better serve the community.

Senior residents have gotten together with NY Cares to organize gardening and landscaping projects in the abundant green spaces around the buildings. Vegetable gardens and hoop houses – mini greenhouses that grow plants year round – are among the efforts that bring together seniors and children.

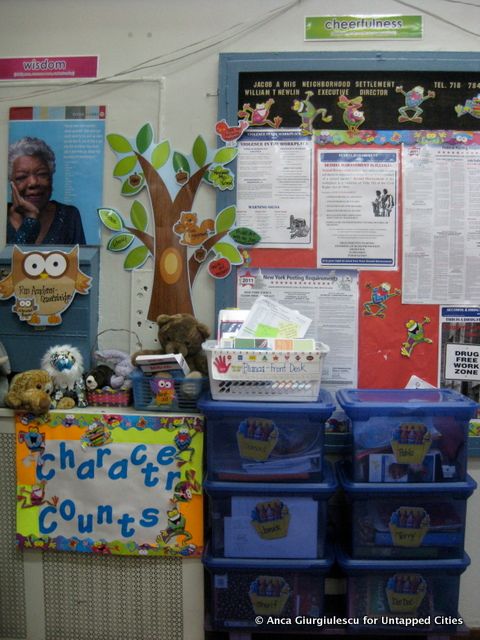

The keystone of community life is the Jacob Riis Community Center that houses a multitude of activities, including senior events and projects during the day; afternoon programs for youth including computer classes, tutoring, and sports; programs for immigrant residents including ESL classes; health and wellness workshops and screenings; a community garden and a local CSA; and community meals.

But it will likely take a lot more than beautification projects and community centers to make Queensbridge safer. The Queensbridge community website seems to reflect this current mix of progress and fear, with the tagline: “Send us info about Queensbridge Area: Arts, Armed Robberies, Stabbings, Gun Fights, NYCHA complaints, Events, Etc.” The site also includes a recap of 2013 shootings with a graphic image of bloodsplatter and a link to an Onion video on “How to survive being shot point blank in the chest.” Nevertheless, our tour highlighted Queensbridge’s efforts to put the “public” back in “public housing” through its dedication and access to shared spaces that bring life from inside the buildings into the green and vibrant outdoors.

See more tours from the Municipal Art Society here.

Subscribe to our newsletter