Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

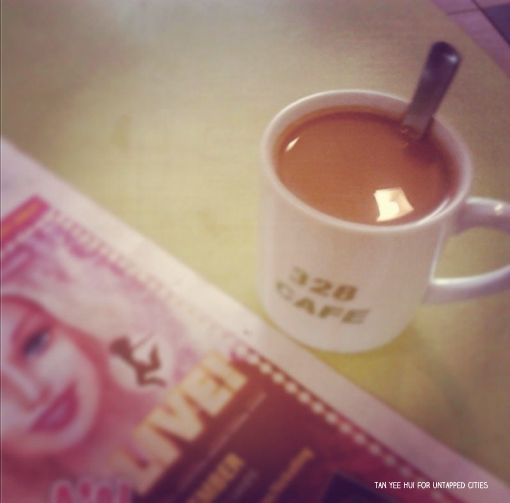

Earlier, we wrote about the rise of cafe culture in Singapore, with new cafes opening regularly in Singapore’s new hotspots. This is happening at a rate so rapid that the pattern is more than academic; it is palpable, striking to anyone traversing the outskirts and venturing out of the city’s traditional consumer and business hubs.

But what does the term ‘cafe culture’ mean in Singapore? It’s not entirely synonymous with expensive drinks, a privileged clientele, and latte art. Arguably, cafe culture was not imported into Singapore when Starbucks first arrived here almost 20 years ago; it has existed long before that and remains an indispensable part of local culture, although it tends to be less glitzy and less documented by those in social media.

Since Europeans started arriving and mingling with local South-East Asians in the late 1700s, cafe culture has thrived here after being adopted, localized, and re-branded as kopi (Malay for coffee) culture. An estimated 2000 kopitiams (coffee shops) can be found wherever people live, work, and pass through, as compared to around 40 Western-style independent cafes.

Unlike what most people in the West think of as coffee, kopi is usually made with Arabica beans rather than Robusta beans, a sock filter and condensed milk. It comes in a multitude of varieties, usually referred to by their local names – regular kopi, kopi o, kopi si, kopi siew dai – and multiple varieties of each, in a complex system that confounds even some locals.

Because your cup of kopi will rarely cost you more than a dollar, there is no pressure to milk your drink for the $5 you paid for it, no pressure to Instagram it from every angle. The pleasure of enjoying a cup of kopi is not restricted to people of a certain socio-economic class, age group, or cultural influence. At a kopitiams, you won’t see people working on their laptops. Instead they are pouring over the morning paper, bantering with the kopitiam uncles/aunties, talking with friends, or watching the world go by. In a way, the kopitiams, inherently more egalitarian and less exclusive than the new wave of cafes, are perhaps closer to embodying the true spirit of ‘cafe culture,’ and have been doing so for centuries.

The new cafes are popular, but it’s not hard to see why the kopitiams aren’t going away soon. For one, coffee and kopi taste different. They also arguably serve different purposes. Need wi-fi and a power point? Cafe. Sick of sweating in the tropical heat and seeking AC? Go to a cafe. Want a taste of Singaporean soul food? Kopitiam. On a budget? Kopitiam.

This duality between the traditional and modern, between local and the imported Western culture is perhaps emblematic of what life in Singapore looks like these days. In Singapore, where food is an essential component of national culture and identity, the proliferation of these cafes implies choice, which can only be a good thing. While many have a preference for either kopi or coffee over the other, each feeds a different need, and in a city which cherishes its food, it looks like both kopitiams and cafes are here to stay.

Subscribe to our newsletter