100th Anniversary Great Nave Tour at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine

Celebrate the 1925 construction of the stunning nave inside the world's largest Gothic cathedral!

The firehouse is open for people wanting to stop by and pay their respects. I go up to one of the firemen and give him the donuts and say, “I just want to thank you and shake your hand.” They are always very warm and grateful. When my emotions get the best of me, I make a quick exit and quietly sob on my way back home. It is a small gesture…just some donuts. But I will never stop doing it and will never forget.

New York honors our heroes, we honor our fallen and we remember September 11 in many ways publicly and privately. On March 25th, another anniversary of a major tragedy is soon upon us. This is the 100th anniversary of the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire and though not all remember the story, each and every one of us benefits from the lessons learned that day.

Back in 1911, The Triangle Shirtwaist Company was a sweatshop owned by Max Blanck and Issac Harris that was located in the Asch Building near Washington Square at 23-29 Washington Square East and Greene Street. Workers, mostly young immigrant women, toiled nine hours a day during the week and seven on Saturday for meager wages making women’s blouses. It was the end of the day on Saturday March 25 at around 4:45pm when a fire broke out on the eighth floor in a scrap bin. No one is quite sure how the fire started. One theory is that it was a carelessly tossed cigarette. Other reports claim that the engines that ran the sewing machines caught fire. But with all the highly flammable bolts of cloth and scraps, the fire spread rapidly.

The company had three floors of the building; eight, nine and ten. Each floor had exits, freight elevators, a fire escape and stairways. Flames prevented workers from using the Greene Street staircase. The other door to the Washington Square staircase was locked. The owners locked the workers inside to prevent theft and from workers taking breaks or leaving early. Dozens escaped by going to the roof and many others managed to get on the elevators before they ceased operation. But within minutes, there was no escaping the flames. The fire escape was flimsy and might have been broken before the fire started. A few managed to use the fire escape but it soon collapsed from the heat and the overload of people trying to flee. Many plunged to their death when the fire escape buckled.

The fire department arrived quickly, but their ladders only reached the sixth floor, missing the fire by two floors. The water pressure was also not powerful enough to reach up to the flames. Desperate employees jumped from the top floors trying to reach out and grab the rungs of the fire truck ladders; only to plummet to their death. In a futile attempt to go down the elevator shaft, the workers pried open the elevator doors and tried to slide down the cable and land on top of the elevator car. Many more jumped in the elevator shaft and fell on top of the car. The elevator operator could hear the bodies thud over his head.

A crowd had gathered below. As panic-stricken workers stood in the windows, the crowd below begged them not to jump and to wait for help, but inevitably, they would jump. Many jumped while on fire and the site of the women with flames encompassing their hair and clothes created hysteria in the crowd below. They were weeping and screaming and fainting in the streets. Firemen tried to use a net to catch the women, but too many jumped at once and the net broke. The bodies were piling up on the sidewalk and street. Some bodies smashed through the glass sidewalk vault lights and fell into the basement below. The bodies on the street were soaked with water from the fire hoses.

Among the crowd below was a young Frances Perkins. The fire affected her immensely. She went on to be the very first woman Cabinet member and served as Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Secretary of Labor from 1933 to 1945. She fought hard for workers and pushed through legislation such as the Social Security Act and the Fair Labor Standards Act. Witnessing the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire played a part as she paved the way for labor reform.

In the end it was estimated 62 workers jumped to their death. Twenty five bodies were found on top of the elevator cars. Nineteen bodies were found melted together against the locked door to the stairway. 146 people perished in the fire. 30 were men. The youngest was 14. 71 were injured. As night fell and the fire subsided, rescuers began removing the bodies by wrapping them in blankets and lowering them with ropes out the windows to the street below. Searchlights were used to light up the building, creating a grisly scene as the wrapped bodies, bathed in light, went down the side of the building.

Police had sent for 75 to 100 coffins but only 65 were available. The Commissioner had to send a steamer up to the Bronx to fetch more coffins from the Metropolitan Hospital. The families of the workers had been streaming into the area and the police station, hysterical to find out about their loved ones. A makeshift morgue was set up near the East River. It was a horrific scene. The bodies were placed in the coffins in whatever condition they were found and family members (and also the curious) were allowed to come in and walk down the rows of open coffins trying to identify their family members. Some of the dead were unrecognizable. Six victims were not identified until 2011. Independent researcher Michael Hirsch pored over reports and documents and was able to identify those six. A documentary about the fire and the search for the identities, “Triangle: Remembering the Fire”, premiers on March 21st on HBO.

There was a trial for the two owners of the factory. Blanck and Harris stated their building was fireproof and had just been approved by the Department of Buildings. The case focused on the fact that the workers were locked inside. Workers gave their testimony, but the owners were found not guilty. Each family that lost a loved one received 75 dollars from the Triangle Company. Blanck and Harris, through their insurance policy, received 400 dollars for each employee that was killed.

Cornell University holds all the documents and history of the fire at the the ILR School Kheel Center. Their website is amazing. There is a list of all those who died and their ages. When you click on a name, it tells you where they immigrated from and even their address. Clicking on a random name I find Rosie Grasso, 16. She had lived in the US for five years at 174 Thompson Street. It gives me chills. The website has photos from the burned out factory, from the morgue, from the marches and protests that happened afterward.

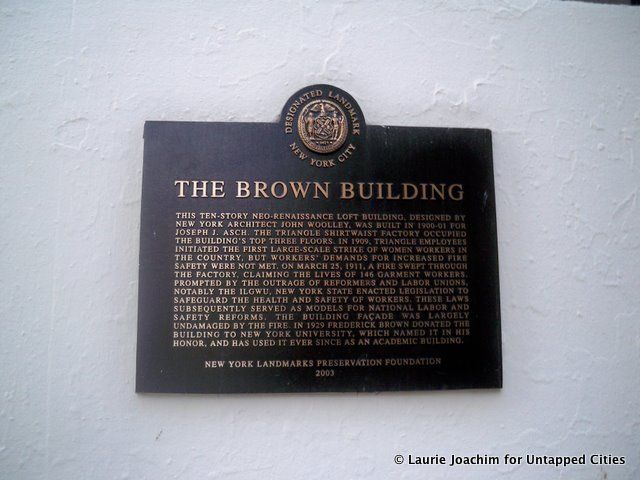

Today, the Asch building is now part of the NYU campus. It is called the Brown Building of Science. Classes are held in the rooms on the floors where so many perished. I went to see the building and take some photos of the plaques that were placed there by the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union, and other organizations. The building is now a National Historic Landmark as well. It was quiet there on a Sunday afternoon in the shadows of the side street near the park. I felt the heaviness of the building. It is agonizing to look up at those windows and think of the hopeless despair that went on inside. The cobblestone streets are still there too. And that is what gave me the most anguish, to walk on those cobblestones where so many fell to their death; those streets where the crowd stood in helpless horror.

This March 25 there will be a vigil at the building at 4:45 pm. Everyone is encouraged to bring a bell to ring to honor the dead. I will be there.

https://rememberthetrianglefire.org/2011/02/146-bells/

The way we work today, in offices with building codes, exits, stairwells, fire alarms, and fire drills”¦all of this we have due to the sacrifices made that day in 1911. The next time there is a fire drill at my office, I promise not to groan as I gather my belongings and go out to the lobby to wait instructions. I promise to be thankful.

Subscribe to our newsletter