NYC’s Forgotten ‘War on Christmas Trees’

Discover how an obscure holiday crackdown affects festive street vendors today!

When Justin Rivers, now Chief Experience Officer of Untapped New York, first contacted us in 2013, he was in the midst of fundraising for his play, The Eternal Space, about the demolition of Penn Station. It was the kind of message I live for — ordinary New Yorkers with extraordinary ideas. If Untapped New York can provide a lift and fulfill a dream, we will jump at that opportunity. Rivers had found in me, another Penn Station fan — both of the old one and uncannily, of the currently hated one. I grew up on Long Island and knew it as a visitor, then as a commuter when my father forced me into a journalism internship the summer of my high school senior year, and then as an adult full-fledged New Yorker. I loved that I knew all its passageways and shortcuts, its proliferation of puns for no reason, its many remnants of the old Penn Station hidden in plain sight.

It was these remnants that gave me an idea on how to support The Eternal Space. For the play’s Kickstarter campaign, we would partner with Rivers to create a tour of the remnants, something which I had already been writing about for several years. I am no tour guide, but Rivers, already an old Penn Station fan (obviously, if he was writing a play about it) became an unexpected tour guide phenomenon. The Eternal Space went on to have a successful run Off-Broadway, and we’ve been hosting sold-out tours of the Remnants of Penn Station twice a month for the last seven years.

I firmly believe Rivers is responsible in large part for the latest renaissance in Penn Station enthusiasts. His tours (of which thousands and thousands of people have attended) and the interviews he has given for many news outlets domestic and international, lit a fire. I know no better storyteller than Rivers, as evidenced by the tour “groupies” he has — but importantly for us, he’s also a historian at heart and a stickler for facts.

One of the remnants Rivers highlighted on his tour from the very beginning was the Penn Station powerhouse, or more officially, the Penn Station Service Building, located at 236-248 West 31st Street. Rivers has long called it Penn Station’s largest remnant. The granite building, which faces the south side of Madison Square Garden, once served as Penn Station’s coal-fueled power plant. Just recently in late January, we published an article showing readers what the building looks like inside. We always knew the day would come when this building, built from the same granite as the lost Penn Station, would be at risk of demolition. That day has come.

In 2016, over a thousand people attended the symposium we organized with The Museum of the City of New York and The Design Trust for Public Space at Cooper Union about the future of Penn Station. The timing of our event came just as Governor Andrew M. Cuomo announced his plans for a complete overhaul by 2021. Penn Station proper has not been completely overhauled yet, but some major changes have already come as part of the Moynihan Station transformation.

Something that has flown far under the radar, compared to the jubilant reception that was the opening of Moynihan Train Hall at the end of 2020, has been the full proposal for the Empire Station Complex. It was first announced in January 2020, as part of Cuomo’s State of the State Initiatives. Moynihan Train Hall was just the first piece of the larger plan, which has the intent to establish ” the proposed blueprint for an integrated public transportation complex to revitalize New York’s Pennsylvania Station (Penn Station) area and give New York City the world-class intercity transportation hub it deserves.” One key line in the introduction in the draft environmental impact statement for the Empire Station Complex plan is as follows:

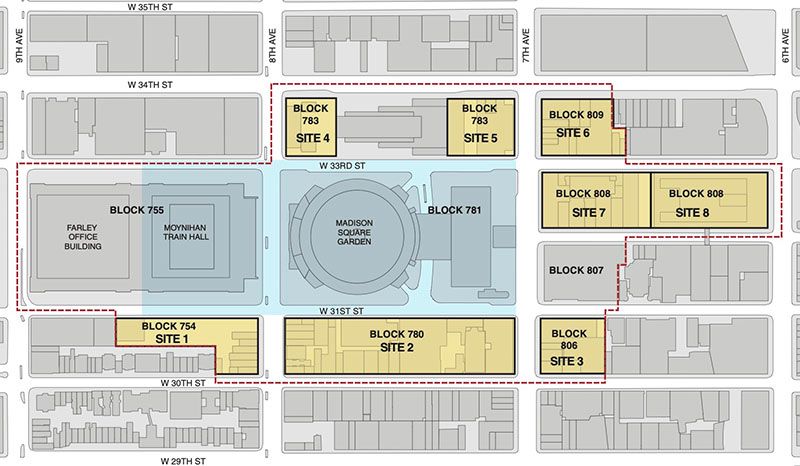

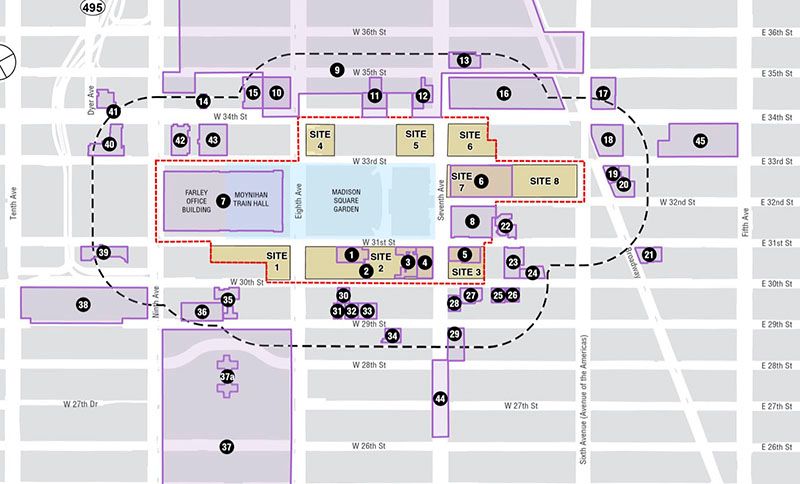

The railroads are also undertaking planning for an expansion of Penn Station potentially to the south into Block 780 and parts of Blocks 754 and 806 to accommodate up to nine additional tracks and five new platforms. Both the reconstruction and expansion of Penn Station are essential infrastructure projects for the future of New York, long talked about but finally achievable under the leadership of Governor Cuomo.

Buried even further in the architectural and cultural resources section are the buildings that would be impacted as part of the Empire Station Complex plan. This list of buildings at risk includes not only the Penn Station Service Building (listed as having “Significant Adverse Impact from Development on Site 2”). There are 10 buildings that could be eligible for New York City landmark designation and 38 buildings that could be eligible for State and/or National Register status. This is no small number. This block, 780, has already survived two demolition attempts as part of the Access to the Region’s Core (ARC) in the 1990s and the “Penn South” plan in 2015

The Penn Station Service Building or powerhouse (building #1 in the above map) would be eligible for New York City landmarks and New York State and National Register status. According to the research already done for the draft Environmental Impact Statement for the Empire Station Complex, the building meets National Register Criterion C for the areas of architecture and engineering. The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission “has determined that it also appears to be eligible for NYCL designation.” Here is the rest of the description from the draft report:

Located at 236-248 West 31st Street across from MSG, the Penn Station Service Building was built in 1908, two years before the completion of the old Pennsylvania Station, which was located directly to the north. McKim, Mead, & White designed the structure to supply electricity to the engines going in and out of the station and compressed air for braking and signaling mechanisms. It also generated heat and light for the station. The five-story building is a simple Classical structure clad in the same granite of which the station had been constructed. The façade is divided into a large three-story section set on a plinth and capped with a projecting stone cornice, and an attic story with windows. Across the main portion of the façade, double-height Doric pilasters alternate with windows secured with iron grills. The attic story is surmounted by a stone cornice that is smaller and less elaborately molded than the one above the base.

The buildings on Block 780, which includes the Penn Station Service Building, the Fairmont Building at 239-241 West 30th Street, St. John the Baptist Roman Catholic Church Complex at 207-215 West 30th Street and the Penn Terminal Building at 370 Seventh Avenue, would be impacted if the track expansion project proceeds. $1.3 billion of State budget (funded from taxpayer dollars) has been allocated for acquisition of buildings and properties for this, but it is currently undetermined which agency would be in charge of the acquisition or how the process would work. There is one public hearing scheduled for the Empire Station Complex on March 29th. Here is the official legal notice and the Zoom link to register.

Rivers says,

“Let’s not demolish Penn Station all over again! Moynihan Train Hall is proof that the past and present can co-exist not only for the sake of utility but also for the sake of beauty. These structures should be preserved and thoughtfully integrated into the Empire Station Complex.”

This is the launch of the Coalition to Save the Penn Station Powerhouse, led by Untapped New York, the Historic Districts Council, and the City Club of New York, with additional founding partners: 29th Street Neighborhood Association, Human-scale NYC, Landmark West!, and the Victorian Society of New York. Here are the first steps the Coalition is taking:

1. Circulating a petition to save the Penn Station power plant and surrounding historic buildings that are at risk:

2. Working with members of the coalition to submit a formal Request for Evaluation to the Landmarks Preservation Commission to kickstart the landmarking process

Subscribe to our newsletter