Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

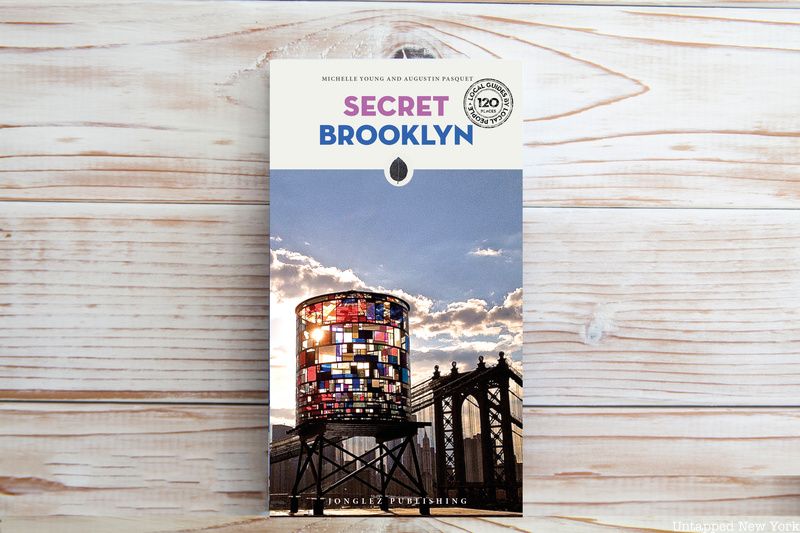

Abandoned trolley cars, the site of the largest Revolutionary War battle, and a Captain America statue inside a department store are just a few of the quirky and hidden places featured in the new, 3rd edition of Secret Brooklyn: An Unusual Guide. Created by Untapped New York’s founder Michelle Young and CEO Augustin Pasquet, this guidebook contains more than 100 weird and wonderful sites spread throughout the borough. Inside, you’ll also find interviews with New York City characters like the artist Tom Fruin (whose iconic water tower graces the cover!). Within the pages of this handy guide, written for New Yorkers and tourists alike, you’ll uncover one of the first free African American settlements in New York City, a former military cemetery turned public park, wild parrots, remnants of a lost railroad tunnel you can get a drink in, and so much more. Here, we take a sneak peek at 5 new sites excerpted from the new edition of Secret Brooklyn, which you can order now. Get an autographed copy and free shipping when you use the promo code “BROOKLYN” at checkout in the Untapped New York shop!

On the Red Hook waterfront, tucked behind Food Bazaar supermarket and the Beard Street warehouses is the last remnant of a bold experiment to bring back trolleys to Brooklyn. From the 1990s to the 2000s, the Brooklyn Historic Railway Association (BHRA) worked with the NYC DOT to extend the trolley line into Red Hook. For a period of time, a one-mile loop of trolley track went from the warehouses into the Red Hook neighborhood along Conover Street and Van Brunt Street. The pilot was short-lived however, with the city determining that trolleys were not the best option for improving transit access in Red Hook.

The rail tracks were quickly removed thereafter in road repaving in 2004 and BHRA co-founder Bob Diamond lost access to the warehouse the Association was using to store most of the trolleys. For about ten years, four trolleys remained on the Red Hook waterfront, but flooding from Hurricane Sandy significantly corroded the cars. The O’Connell Organization donated the trolleys, two of which went to the Sherburne Falls Trolley Museum in Massachusetts, including cars 3299 and 3321, the last trolley car ever to be built in the state. Sherburne Falls Trolley Museum is currently fundraising for a cosmetic restoration of the cars. One trolley remains on the Red Hook Waterfront — the 3303 Boston T Green Line car dating from 1951. It has been painted blue in the last few years but the T logo is still visible. The trolley car now reads NO STOPS on its front placard.

In the Hasidic Jewish area of Williamsburg, you may see a miniature police station that looks straight out of a movie set. Located on a small traffic island on Lee Avenue just off the Brooklyn Queens Expressway, it could be the more utilitarian version of the Tardis police box from Doctor Who. And in a way, you would be going back in time if you were to go inside. This station was part of an official NYPD neighborhood watch post in the 1980s for the local area, according to a retired NYPD detective we spoke to who was previously assigned to this very station, but the station is no longer used by the NYPD. The retired detective also told us the station itself was built by the local community to have a police presence, particularly during Shabbat from Friday evening to Saturday when electricity and phones cannot be used, as per the religious tenets in the Orthodox Jewish community. The community could just walk over to the police station if help or emergency was needed, the detective says.

When he was a rookie assigned to this station, he says it was originally “built for an old-timer – Police Officer Danielski, this was his post.” In addition to the watch post, there were also House of Worship (HOW) patrol cars that would monitor activity in front of synagogues. Despite some aging, a little graffiti, and some weeds, the station is fairly intact on the exterior. The POLICE sign in a blue Helvetica-style font is on three sides of the building. There’s a door with a numeric keypad on the side facing Keap Street with an air conditioning unit on top. Blinds are drawn on all sides but on the side facing Williamsburg Street East and the BQE, two top windows were tilted open. It is still used by the Hasidic community, as we saw lights on inside on a Friday night.

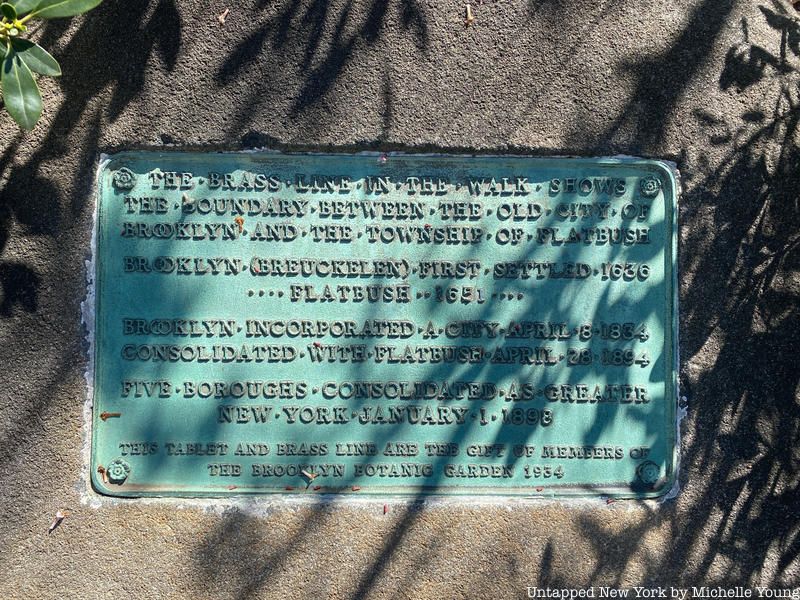

Tucked inside the Brooklyn Botanic Garden’s Flatbush Avenue entrance is a bronze patent line embedded into the asphalt that extends across the walkway. Few visitors will know that it denotes the former geographical boundary between Brooklyn and Flatbush. At one end of the line, a stone marker has a small bronze plaque that reads:

The brass line in the walk shows the boundary between the old city of Brooklyn and the township of Flatbush. Brooklyn (Breukelen) first settled in 1636. Flatbush 1651. Brooklyn incorporated a city April 8, 1834. Consolidated with Flatbush January 1, 1896. Five boroughs consolidated as greater New York January 1, 1898.

Before New York City encompassed the five boroughs it’s known for today, Brooklyn was its own city. Brooklyn (originally Breuekelen, in Dutch) was first settled in 1636 and incorporated as a city in 1843. Not long after came the village of Flatbush, which originates from the Dutch word Vlacke (meaning flat), first settled in 1651. Flatbush, though part of Brooklyn today, remained independent from its neighbor until 1894. That’s just a couple of years before New York City was “consolidated” into the five boroughs. The heart of the village of Flatbush was located where Flatbush Avenue and Church Avenue intersect today, and where the old Dutch Reformed Church, built in the last decade of the 18th century and Erasmus Hall, where an old clapboard schoolhouse dating to 1786 still exists. The northern border between Brooklyn and Flatbush runs through what is now Prospect Park and Brooklyn Botanic Garden.

Shoppers going in to grab one of the innumerable home products on sale at Bed Bath & Beyond may be surprised to see a 13-foot-tall bronze Captain America statue upon entering Liberty View Industrial Plaza. Captain America is so tall, his shield reaches into the mezzanine level of the building’s atrium. He holds his iconic star shield aloft with his left hand, with his right hand clenched into a fist. On the top of the bronze plinth are the words “I’m just a kid from Brooklyn,” a line from the 2011 film Captain America: The First Avenger. In this modern era, it seems rare for any statue to arrive without controversy and this one was no different.

The Brooklyn-based sculptor David Cortes, of Cortes Studio, was commissioned by Marvel to make the design for the 75th Anniversary of Captain America, the comic book character created by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby in 1941. Cortes, a native Brooklynite, is known for the figurines he’s made for Marvel and DC Comics. The one-ton statue was cast in Asia by the company Comicave and unveiled at the 2016 San Diego ComicCon. The original plan was to tour the statue around the country, but the idea was met with unexpected resistance. “All of a sudden, there’s all this red tape,” says Cortes. From Comic Con, the statue moved to Prospect Park for two weeks. Marvel fans came en masse and in costume to the rain-drenched ceremony, but other parkgoers complained about the perceived commercialization of the public space. Afterward, Captain America went on display in front of Barclays Center for about a month and a half.

Additional controversy over the statue was rooted in Captain America’s origins. In the comic books, his alter ego Steve Rogers is from the Lower East Side and was the child of Irish immigrants. The film, and more recent comics, shifted Captain America’s origins to Brooklyn. Purists of the comic books protested that the statue should rightfully be in Manhattan. The sculpture was then gifted by Disney, the parent company of Marvel to Liberty View Industrial Plaza in the fall of 2016. Ian R. Siegel, Senior Project Manager at Salmar Properties says that the sculpture needed to find a permanent home in Brooklyn and they felt that the 1918 former U.S. Navy building “was the perfect home.” He adds that a lot of Marvel fans of all ages come by to take photographs with the sculpture.

Most straphangers who pass through the Brooklyn Borough Hall subway station barely notice the two darkened windows that are set within the blue tiling on the upper level of the station. But look carefully and you will see the faded words “COMMUTER BANKING” at the top. On the lower part of the window, the hours are still visible: “MONDAY THROUGH THURSDAY 8A.M. TO 6 P.M.” as well as a small, yellowed button that would have summoned the teller.

These commuter banking windows, made by Diebold Incorporated out in Ohio, were once run by the Brooklyn Savings Bank at least through the late 1960s and likely through the 1980s until the bank closed. Untapped New York tour guide Justin Rivers believes that this section of the subway station was added in the early 1960s when the New York City Transit Authority was performing large capital improvements, including subway platform extensions on the former IRT line. There is little written in the press, past or present, about this helpful banking window, but the initiative was clearly part of a larger attempt by banks to make banking more convenient starting in the mid-century. In 1923, New York State passed a new banking law that allowed savings banks to open branch offices for the first time, which led to a flurry of new creative banking options.

Learn more about each of these sites and dozens more in the latest edition of Secret Brooklyn. Get an autographed copy and free shipping when you use the promo code “BROOKLYN” at checkout in the Untapped New York shop!

Next, check out 180 Fascinating Secrets of New York City

Subscribe to our newsletter