Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

In 1857, the city held a design competition for Central Park. The winning plan, by Frederic Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, was named ‘the Greensward Plan’ and featured an English style landscape with meadows, lakes, hills, winding pedestrian paths, and many trees to block the view of city buildings. The park was envisioned to be world class, on par with the greatest parks in London and Paris.

In today’s post, we focus on some of the most naturalistic features and areas of the park that were included in the original Greensward Plan. Like all the landscapes in Central Park, these beautiful areas are all man-made in areas that were irregular, containing swamps and farms. Most of that was completely razed, though some existing trees and many rock outcrops were incorporated into the plan. These naturalistic areas and elements were intended by the designers to allow city dwellers to connect with nature and experience the change that comes with seasons, weather conditions, and different times of day.

1. The Ramble

The Ramble, a 38 acre woodland in the middle of the Park, is a quiet oasis from the busy city. Here Central Park is at its most naturalistic, with walking paths winding through the trees.

When the park first opened for public use in the winter of 1859, some areas were still being developed, including the Ramble. Check out this 1869 New York Times article that describes how “those ladies, and all other persons who have failed to visit it, have deprived themselves of a great deal of pleasure.” The dated language makes it comical, but it is fascinating to read about the vision of the Ramble by original design.

Where to find it: The Ramble is located Mid-Park from 73rd – 79th Streets

Steps down to the Ramble Cave

2. The Ramble Cave

The Ramble Cave, also known as the Indian Cave, was created from a natural cave discovered during park construction and developed for Lake rowers who could leave their boats to explore the area. Unfortunately, in the early 1900s, the cave was the site of several crimes and at least one suicide. In 1929 The Times reported that 335 men had been arrested for “annoying women” in the park, especially at the cave. Eventually, the cave became too dangerous to maintain, so it was sealed at both ends and the inlet was filled. Today, the cave is inaccessible to visitors, but the entrance is visible from the path above and it adds a feeling of mystery to the area. The view of the steps is however, at the time of this writing, obstructed by a fallen tree.

Where to find it: On the west shore of the Ramble, north of Gill Bridge and south of the Oak Bridge.

3. The Ramble’s Role in LGBT History

Another aspect of the Ramble is its important role in LGBT history. The secluded area has been known as a gay cruising spot since at least the early 20th century. In the 1920s, this lawn with the mature tupelo tree (pictured) was referred to as the “fruited plain.”For many years, the Ramble was regarded as a seedy area, however, in reality the individuals who went there for sex were more often the victims than perpetrators of crime.

Eventually, during the late 1970s, there was a series of very brutal attacks on gay men in the Ramble. One proposed idea to manage the area was to develop a seniors’ center there – a dismissive solution to the real problem of hate crime – which fortunately was rejected. Today, the Ramble has a visible police presence. Nature walks and bird watching seem to be a bigger draw than sex cruising – though unsurprisingly we have stumbled upon several couples (gay and straight) making out.

Where to find it: This three-trunked black tupelo tree is thought to pre-date the Park, from around 1862. It sits in its own meadow in the middle of the Ramble, near the West 70s.

4. The North Woods

The North Woods is denser, larger, and less populated than the Ramble. Although it is landscaped and man-made, it is allowed to grow naturally and fallen trees and snags are allowed to stay where they land. Parts of the North Woods, including the bucolic Ravine, are unlit at night. This area of the park was designed by Calvert & Vaux to replicate the beautiful Adirondacks in upstate NY.

Where to find it: Mid Park from 101nd – 110nd Streets.

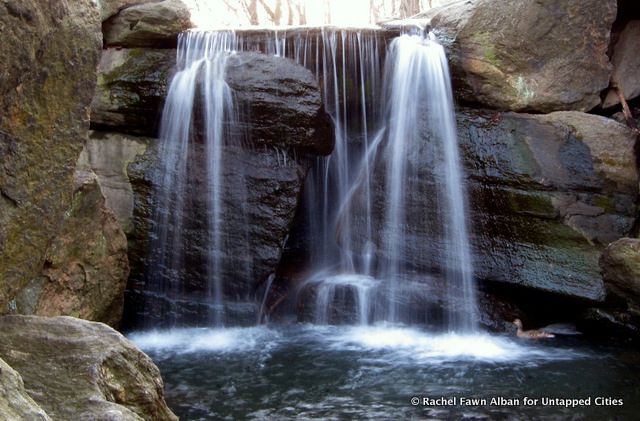

5. The Waterfalls

There are at least five waterfalls in Central Park, all completely man-made, and most of which are located in the Ravine, the stream valley section of the North Woods. The water that flows here is actually New York City drinking water that comes from a 48-inch pipe hidden by the rocks at the Pool Grotto on West 100th Street. Yet the waterfalls look amazingly natural. Charming stone bridges cross the stream, and everything is cool and quiet. Watching the water gush down giant boulders into dark ponds, it is easy to forget this is in the middle of Manhattan.

Where to find it: Don’t go chasing these. Enter from the West side through Glen Span Arch around 102nd Street and follow the stream, which is called the Loch.

6. Prehistoric Rocks

Every day in Central Park, children and adults play, climb, and relax on ancient rocks which are approximately 450 million years old. Besides the trees, which are very young by comparison, the only natural feature in the Park that the designers incorporated into their design plan are these metamorphic rocks.

The rock outcrops in the park are Manhattan schist and Hartland schist. According to wikipedia:

Manhattan schist and Hartland schist were formed in the Iapetus Ocean during the Taconic orogeny in the Paleozoic era, about 450 million years ago. During this period the tectonic plates began to move toward each other, which resulted in the creation of the supercontinent, Pangaea.

Some of Central Park’s rocks have what is called “Glacial Striations“, which are grooves in the rock that were formed when sediment embedded in the bottom of the moving glacier was dragged across the rock, leaving groove marks . Looking at these grooves, it is fun to imagine the big glacier moving through the park.

Where to find it: All over the park.

7. Historic Trees

When Central Park was built, the city planted more than 270,000 trees and shrubs and preserved a handful of trees that were original to the area. Today, only about 150 trees are left from the time of Olmsted and Vaux, but many of the trees acquired over the years have a unique story. These Yoshino Cherry trees along the east side of the Reservoir may be the original trees presented as a gift to the United States by Japan in 1912. They are among the first trees to bloom in the spring, before the Kwanzan Cherry. The delicate blossoms drop quickly before the trees green out, and stay leafy for the rest of the season.

Where to find them: Along the east side of the Reservoir around East 90th Street.

Ken Chaya and Edward Sibley Barnar are friends who spent two and a half years making a lovely illustrated map that painstakingly details 19,933 trees in the Park. Titled “Central Park Entire,” the map includes 170 different species, including 33 of these wisteria trees:

8. Wisteria Pergola

Olmsted and Vaux perched a Wisteria Pergola overlooking what used to be the concert grounds and The Mall. This is not a naturalistic feature of the park, but it is an example of nature and design working together. The long, latticed patio, 130 feet long by 25 feet wide, and many wooden supports are interlaced with wisteria vines that have gotten heavy and extremely thick over the years. Though the view of The Mall is now obstructed by the Bandshell, it is still a beautiful place, especially in the spring when the wisteria bloom their pale, lavender blossoms.

Where to find it: Overlooking the north end of the Central Park Mall just south of 72nd Street.

See more photography from Rachel Fawn Alban.

Subscribe to our newsletter