Fiber Arts Take Over a Former Seaport Warehouse in NYC

See waterfalls of fabric, intricate threadwork, massive tapestries, and more!

Murray Hill is a neighborhood on the east side of Manhattan that is predominantly residential with plenty of historic buildings. The neighborhood is very diverse, in part thanks to its many consulates and proximity to the United Nations in neighboring Turtle Bay. Named after Robert Murray, a merchant during the mid-1700s, Murray Hill was historically isolated from the rest of Manhattan since it was situated on a steep glacial hill. Around the turn of the century, the area quickly became wealthier and more developed, attracting figures like J.P. Morgan and the Roosevelt family. Many structures in Murray Hill are New York City landmarks, from two- and three-story homes to skyscrapers. With a small Armenian, Orthodox Jewish, and Scandinavian cultural community, here are 18 secrets of Murray Hill.

Sniffen Court is a small row of mews in Murray Hill running perpendicularly southwest from East 36th Street. Sniffen Court is one of the city’s smallest historic districts, consisting of 10 two-story brick Romanesque Revival stables. The row of mews was built between 1863-1864 between 3rd Avenue and Lexington Avenue, likely by local architect John Sniffen. Though many mews were constructed in lower Manhattan around Greenwich Village and West Village, Midtown never had many alleys, making Sniffen Court an anomaly in the area. Originally built as carriage houses, many were converted for other users, including the clubhouse and theater of the Amateur Comedy Club.

Many famous artists lived at Sniffen Court, most notably Cole Porter, who owned both 2 and 4 Sniffen Court while in residence at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel. Malvina Hoffman, a sculptor known for her life-size bronze sculptures, had her studio at the Court (and created plaques of horsemen on the rear wall), which was later the residence of author Pearl S. Buck. Over the years, many of the homes shifted to architecture offices and music studios for figures like Lenny Kravitz. The Doors also used Sniffen Court for the cover of their album Strange Days.

Regarding Oysters is a speakeasy hidden on the top floor of a Murray Hill brownstone. Run by Georgette Moger, the speakeasy hints back to 1920s Paris but with a view of the Chrysler Building. The speakeasy is essentially an oyster salon and cocktail experience where guests can shake their own cocktails and shuck oysters. Cocktails are from Georgette’s book Regarding Cocktails, which captures many creations of her late husband Sasha Pestraske; these include Bees Knees, Penicillin, and the Gin & It, as well as some “temperance Cocktails.” Recipes are printed out on cards and ingredients are sourced by Georgette.

The space is filled with vintage photographs from Georgette and Sasha’s families, as well as a pale green 1860s perfume counter from New Orleans that also functions as the bar. In addition to cocktails, the speakeasy has a small menu of finger foods such as mini madeleines, goat cheese bon bons, and cucumber tea sandwiches. During the shucking portion of the evening, guests wear floral aprons from Fords London Dry Gin and are equipped with a shucking knife, gloves, gold oyster forks, and vintage porcelain oyster plates. Georgette harvests the oysters herself, and each is sprayed with a different aroma and verjus.

Located on Park Avenue, the American Kennel Club Museum of the Dog features all sorts of exhibits focusing on all things dog-related. The museum features one of the largest collections of dog-related art and film of any American museum, as well as exhibits on dogs of important figures like presidents and explorers. The museum began in 1982 with donations from the Westminster Kennel Foundation and other leading dog advocates. The AKC, which has been around since 1884, has maintained the museum since its opening and contributed to sourcing artworks. The museum was previously located at the New York Life Building, as well as in Missouri.

The permanent collection includes dog-related art by painters like Edwin Landseer, Arthur Wardle, and Maud Earl. Artworks range from a painting of a dog on the South Lawn of the White House to a painting of three Japanese chins to a bronze German Shepherd sculpture. The museum also offers interactive experiences in which visitors can learn more about particular breeds or find their dog look-alikes.

The American Copper Buildings are a pair of luxury skyscrapers on First Avenue completed in 2017. Designed by SHoP Architects and developed by JDS Development, the buildings stand at 540 feet and 470 feet respectively. The site on which the towers stand was originally the Consolidated Edison Kips Bay generating station, and redevelopment plans originally included a seven-tower complex by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill that would have also included a public school and park. However, those plans were scrapped for a twin-towers project, and it was decided that the buildings would be partly clad in copper, as well as floor-to-ceiling glass; over time, the buildings will change color into a darker brown, then green as the copper oxidizes.

One of the buildings appears to bend toward the other, in part due to the three-story skybridge on floors 27, 28, and 29. The skybridge includes a lap pool and a lounge, as well as private outdoor terraces. The skybridge measures 100 feet long and is clad in glass with aluminum mesh. The buildings combined have 761 rental units, 20 percent of which are deemed affordable. There is also a climbing wall, pilates studio, catering kitchen, and a hammam (or Turkish bath).

Located on the border of Turtle Bay and Murray Hill, Tudor City is an apartment complex with a storied history. The complex is situated on Prospect Hill, overlooking First Avenue and the United Nations between 40th and 43rd Streets. Tudor City has the distinction of being the first-ever residential skyscraper complex in the world, as well as one of the first planned middle-class residential communities in the city. Development of the area began following the Civil War, in which row houses and single-family homes were erected between First and Second Avenues. Many of these homes were abandoned and replaced by tenements after meat packing houses and factories popped up in the 1870s. After a few decades, The Fred F. French Company began to develop a middle-class complex after taking over some of the former homes.

The complex was designed as apartments surrounding two parks, the Tudor City Greens, starting in the mid-1920s. The southern park originally was designed as a mini golf course, while the northern park had a diverse garden. The apartments were designed in the Tudor Revival style, pulling from many architectural features of suburban homes. The buildings share features including stained glass windows, wooden entrance doors, Tudor-style towers and gables, Tudor roses and lions, and bay windows. Not all the buildings in the complex were built at the same time; No. 2 Tudor City Place opened in 1956 without many of the Tudor Revival features of the other buildings. Tudor City is perhaps most iconic for its sign, which was constructed in the 1930s and has remained ever since, appearing in movies like Taxi Driver, Scarface, and the first three Spider-Man movies.

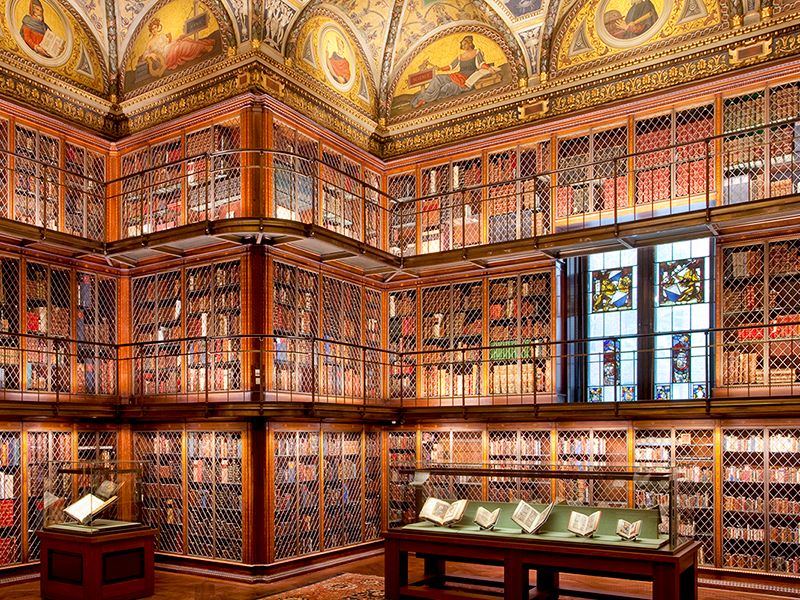

The Morgan Library & Museum was built between 1902 and 1906 next to J.P. Morgan’s New York residence on Madison Avenue and 36th Street. Often called “Mr. Morgan’s Library,” it served as his private study until 1924 when his son gifted the library to the public. The library employed Belle da Costa Greene, whose father Richard was the first African American graduate of Harvard. It was in his study that Morgan dealt with the aftermath of the Panic of 1907. The Annex Building replaced Morgan’s residence with the addition of a gallery and a garden. In 2006, there was an addition of an Italian-inspired piazza crafted by architect Renzo Piano, connecting the library’s three buildings with steel and glass pavilions.

The library is filled with dozens of secrets, starting with the ceiling, which contains zodiac signs. The two signs above the entrance are Aries and Gemini, representing his birthdate and second marriage. Aquarius is positioned across from Gemini, symbolizing the month in which his first wife died. Aries sits across from Libra, the sign he was assigned upon joining the secret Zodiac Club. In addition, there are also (somewhat) secret doors by walnut bookcases near the entrance, which lead to concealed staircases. The library contains an original Gutenberg Bible, a bell from Morgan’s yacht, a medieval tarot card deck, and letters of Henry James, among thousands of other historic documents.

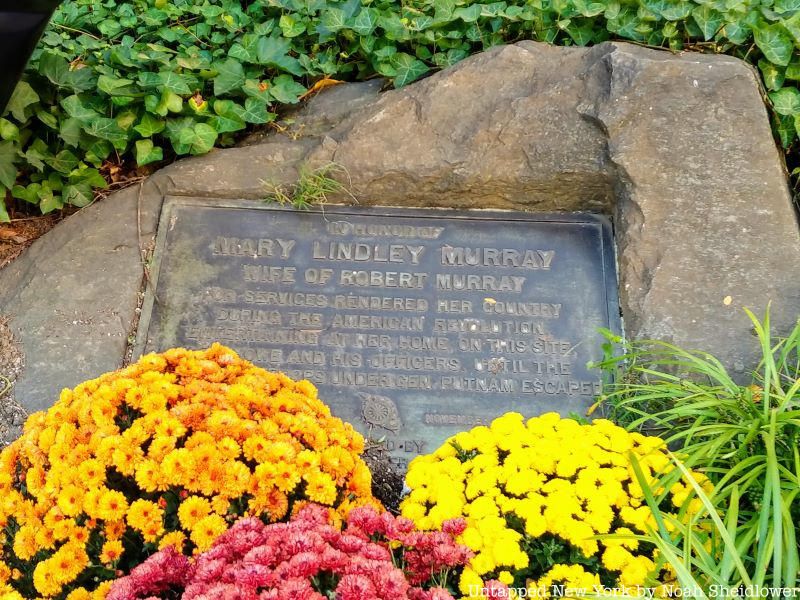

In a traffic island at the intersection of Park Avenue and 37th Street is a plaque dedicated to Mary Lindley Murray, one of the namesakes of Murray Hill along with her husband Robert. Mary Murray was a Quaker woman and American patriot who played an important role during the Revolutionary War. On September 15th, 1776, American forces led by General Israel Putnam retreated from the Battle of Brooklyn to the Bronx, where they met up again with General George Washington. British General William Howe did not want to get away, landing at Kips Bay to trap the army. Howe’s troops were instead detained at the Murrays’ farm, allowing the American troops to escape.

To deter the British army, according to popular legend, Murray hosted a quiet meeting with cake and tea, stalling Howe for hours. It only took about half an hour for the troops to escape, though she kept the men there for over two hours. While Murray played a major role in assisting American forces, her merchant husband held Loyalist ties and bought British goods well into the war.

Despite her husband’s loyalties, Mary Murray’s acts in 1776 allowed the couple to remain in New York City after the war. The Daughters of the American Revolution erected another plaque in 1926 on 35th Street at Park Avenue to commemorate the family’s wartime actions.

The Roosevelt family has had a long history in New York City, starting before Theodore Roosevelt was born. One of just two presidents born in New York City, he was raised at 28 East 20th Street, just a block from Gramercy Park and a few blocks south of Murray Hill. Eleanor Roosevelt was born and raised just west of Murray Hill at 56 West 37th Street, and 20 years later in 1904, she married Franklin after meeting him while he was studying at Harvard.

They moved to a townhouse at 125 East 36th Street in Murray Hill, which still stands today. Sara Delano Roosevelt, Franklin’s mother, paid their rent. Franklin and Eleanor lived in the townhouse for about four years before moving north to 49 East 65th Street, while Sara Delano moved into 47 East 65th Street. It was in that townhome that FDR became more involved in politics after recovering from polio, though the Murray Hill home was truly where FDR got his start. The Murray Hill home was located just a block north of where Ayn Rand lived and wrote much of The Fountainhead, 139 East 35th Street.

Today, a section of Murray Hill and nearby Rose Hill is called Little India, or “Curry India,” for its large Indian population. This section was previously an Armenian enclave home with a handful of restaurants and shops. In the 1920s, the area was predominantly Armenian, with about 8,000 residents who were centered along Lexington Avenue and 23rd Street. Armenians first settled in New York City in search of business and medical opportunities. Immigration picked up in the 1890s after the Ottoman massacres under Sultan Abdul Hamid II. The Armenian Genocide of the 1910s further contributed to the growth of New York’s Armenian community; from 1899 to 1931, nearly 82,000 Armenians immigrated to the U.S., about 75% of whom passed through Ellis Island. The community was filled with stores including MKahayan Imported Food Store, Anooshian grocery store, and Tashjian’s grocery and music store.

One of the last remnants of Little Armenia in neighboring Kips Bay is Kalustyan’s, which sold Middle Eastern spices and foods before expanding to broader culinary products. It was opened in 1944 by Kerope Kalustyan, who came to the U.S. from Istanbul to export steel to Turkey. He instead opened up a food business, which quickly became popular and soon enough expanded to include Indian products as the community began to change demographically. Saint Gregory the Illuminator Cathedral and St. Vartan Cathedral, both of which have served the Armenian community for decades, still remain today. The Armenian community is now scattered across the five boroughs, though the churches still put on Armenian events for long-time residents.

The Consulate General of Poland in Murray Hill is located within the former Joseph Raphael De Lamar House at 233 Madison Avenue. The home was designed by C.P.H. Gilbert, who designed townhouses and mansions across the New York City area. The Beaux-Arts-style mansion was constructed between 1902-1905 with a large mansard roof, numerous balconies, and ornate stonework. Born in the Netherlands, De Lamar worked on a steamship to come to America. After he got settled, he amassed a fortune mining copper, nickel, and silver in California, Colorado, Idaho, Nevada, and Canada. He built a home in Newport and quickly joined many private clubs in and around New York City. His home in Murray Hill was an odd choice since many prominent New Yorkers moved uptown to Millionaires Row on Fifth Avenue.

The home flaunted a billiards room, wood-paneled library, dining room, grand ballroom, and a Pompeian room with an art gallery. De Lamar commissioned Louis Comfort Tiffany to create stained glass panels for the interior. He also installed Otis elevators and an electric hoist for lowering his car into a subterranean garage. There was also a gymnasium and a dog run hidden below the mansard roof, and he employed nine servants.

By the time he died in 1918, he left his daughter an estate worth $29 million at the time. For a brief while, the mansion was operated by the American Bible Society and the National Democratic Club, though in 1973, Poland bought the mansion for just $900,000. Many of the mansion’s original features were renovated and maintained, including its winding staircase.

Scandinavia House, also referred to as The Nordic Center in America, is the cultural center of the American-Scandinavian Foundation. Scandinavia House opened in 2000 at 58 Park Avenue in a modern building designed by the late James Polshek, designer of the Ed Sullivan Theater and the Seamen’s Church Institute. The International Style building replaced a French neoclassical building and the home of art collector Grace Rainey Rogers. The opening of Scandanavia House was attended by King Carl XVI Gustaf and Queen Silvia of Sweden, as well as Norway’s Princess Martha Louise and Denmark’s Princess Benedikte.

The eight-floor building draws from minimalist Scandinavian design with a facade of zinc and glass. Scandinavia House includes the Victor Borge Hall, named after the Danish comedian and conductor, as well as the Halldór Laxness Library in honor of the Icelandic author. The 3rd Floor Gallery features exhibitions of major Nordic artists, such as the current exhibition “On the Arctic Edge” highlighting photographs of the Arctic Circle. Björk Cafe & Bistro opened just a few weeks ago, featuring “butter bread,” or smørrebrød, as well as open-faced sandwiches. The center also offers language classes, film screenings (including the Baltic Film Festival), and classical music performances.

The Union League Club is a private social club on East 37th Street that dates back to the Civil War. Pro-Union New Yorkers originally created the club to foster support for the Union in 1863, promoting ideas of citizenship and anti-corruption. Many of these “Union Leagues” opened across the country as part of a political movement, raising money to support Union and anti-slavery causes in cities such as Philadelphia and Chicago. Four members of the United States Sanitary Commission, including Frederick Law Olmsted, founded the New York League, advocating for a central government. Its first meeting was on March 20, 1863, though just five months later it was nearly vandalized during the New York Draft Riots. The club recruited and trained the 20th U.S. Colored Infantry, who were sent to fight in Louisiana. During World War I the club sponsored the Harlem Hellfighters.

The Union League Club did not move to Murray Hill until 1931, after previous locations near Union Square and Madison Square Park. Benjamin Wistar Morris, who also designed the Cunard Building, designed the current building. Before the move to Murray Hill, the club helped found the Metropolitan Museum of Art and Grant’s Tomb, in addition to helping construct the Statue of Liberty. Theodore Roosevelt, Chester A. Arthur, and Herbert Hoover were among the 15 U.S. Presidents who were members. The list of members is lengthy, including J.P. Morgan, J.D. Rockefeller, and more recently Sandra Day O’Connor, Neil Armstrong, and Margaret Thatcher.

East 35th Street in Murray Hill is the main campus of Stern College for Women, the undergraduate women’s college of Yeshiva University. The school offers degrees in humanities, sciences, social sciences, and Jewish studies, alongside a “Basic Jewish Studies Program” with courses in Hebrew, Bible, and Jewish Law. Established in 1954, the school now serves upwards of 2,000 students.

Yeshiva University purchased 150 East 35th Street, which was the former headquarters of the National Review, founded by William F. Buckley, Jr. Along with a location on Lexington Avenue, the National Review operated out of the East 35th Street location for a few decades. The offices were reportedly cramped and disorganized, but the popular conservative magazine got its start here.

The airline’s president at the time, Albert V. Casey, said about 9,000 jobs would still remain in New York and that the Dallas-Fort Worth area was more centralized for its expanding routes. He revealed that moving operations to Dallas would save millions per year, though New York officials disputed this; the director of the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey even said he would match the Dallas deal. New York officials were critical of the move, especially when American conducted about 2.3 percent of its business in New York City.

In 1975, American Airlines opened its headquarters at 633 Third Avenue between 40th and 41st Streets. American had been headquartered in New York City since 1939 after moving from Chicago. For a few years, the company operated out of the skyscraper near Grand Central, though by 1978, the company announced it would be moving its headquarters to Dallas. Mayor Ed Koch called the move a “betrayal” to New York City.

St. Vartan Park, known as a “secret garden” between East 35th and East 36th Streets on Second Avenue, officially reopened to the public after 20 years in October 2021. Named after St. Vartan Cathedral, itself named after an Armenian 5th-century martyr, the park opened as St. Gabriel’s Park in 1904 next to its namesake church. It received a renovation in 1936 which included the addition of a roller skating track, a pool, horseshoe pitches, and a playground. Because of construction on the Queens-Midtown Tunnel, parts of the park had to be relocated, while others like the playground were lost until 1951. Over 9,200 shrubs were planted as part of another 1984 renovation, which was entirely privately funded.

The park received a final renovation in 2000, after which it was opened exclusively to students at St. Vartan Preschool and their families. It wasn’t until last year that the park opened its gates to everyone in the community, a controversial decision that some believed would destroy the park’s beauty and encourage commercialization around the already cramped neighborhood. Others asserted that the park should service working-class families in addition to the primarily wealthy students who attend the school. The park maintains a garden with magnolia trees, irises, and rose bushes.

Murray Hill, as one of the more historic neighborhoods of Manhattan, is bound to have plenty of listings on the National Register of Historic Places. There are dozens of official New York City landmarks (and about a dozen on the NRHP), including the aforementioned DeLamar Mansion, Morgan Library, and Sniffen Court. Though some consider it Turtle Bay, the Daily News Building on East 42nd Street is one of the most recognizable for its Art Deco style, Daily News sign, and its history as the headquarters of the New York Daily News. The Madison Belmont Building is another standout Art Deco and Neoclassical building, designed by Warren & Westmore on 34th Street and Madison Avenue. The building originally housed showrooms for silk companies as a center of the city’s Silk District.

A relatively newer landmark on the list is the Socony–Mobil Building, constructed from 1954 to 1956 with 45 floors. Original tenants included the Socony-Mobil oil company, which was encouraged to move into the building by the Goelet family. The 28-story building at 2 Park Avenue still maintains much of its original structure from 1926, including its facade of architectural terracotta, vaulted main lobby, and Art Deco main entrance. It was designed by Ely Jacques Kahn, an architect of skyscrapers across New York City who provided guidance to author Ayn Rand.

Though the DeLamar Mansion is perhaps the most famous in the neighborhood, there are a handful of other mansions in Murray Hill that still remain in good condition. The James F.D. Lanier House at 123 East 35th Street was built from 1901 to 1903 in the Beaux-Arts style. It was designed by Hoppin & Koen, both of whom worked in the office of McKim, Mead & White. The home was built for James F. D. Lanier, a Gilded Age banker, and his wife Harriet Bishop Lanier, whose father Heber R. Bishop was a philanthropist known for his jade collection. The home features an enclosed balcony with cast-iron railing, an ornate mansard roof, Ionic pilasters, and an entryway with classical sculptures. With nine bedrooms, seven bathrooms, and three half-bathrooms, the gorgeous home was put on the market earlier this year for a whopping $33 million.

Another Beaux-Arts building is the Civic Club, also known as the Estonian House. The four-story building on East 34th Street was originally built for the Civic Club in 1898–1899, which aimed to reduce poverty in the neighborhood. The Civic Club was short-lived, only in operation until the death of its founder F. Norton Goddard in 1905. The ornate structure was sold to The New York Estonian Educational Society in 1946, still housing some Estonian organizations including the New York Estonian School and the headquarters of the country’s largest Estonian-language newspaper, Vaba Eesti Sõna.

The Chanin Building, a 56-story skyscraper on the border of Murray Hill and Midtown Manhattan located diagonally from the Chrysler Building, was once the third-tallest building in New York City. The Art Deco building was designed by Sloan & Robertson and constructed between 1927-1929. It incorporated the work of sculptor Rene Paul Chambellan, who also did architectural sculpture on the Daily News Building and New York Life Building. The building includes a brick and terracotta facade and incorporates numerous setbacks to give the building a particular massing rather similar to the International Style.

When it opened in 1929, it was the third-tallest building in New York City, reaching 680 feet thanks to its 31-foot spire. At the time, it was only surpassed by the Woolworth Building and the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company Tower. The lobby served as a terminal for the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, and the building hosted tenants including Kimberly-Clark, Fairchild Aircraft, and Sterling National Bank. The building also hosted the U.S. Chess Championships, as well as Barry Goldwater’s 1964 presidential campaign New York headquarters. It hosted one of the city’s first observation decks, charging just 25 cents for admission. Its upper floors previously contained a movie theater and a radio broadcast station.

Next, check out the Top 10 Secrets of Times Square!

Subscribe to our newsletter