Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

Straddled on the border between Brooklyn and Queens is Bushwick, one of the city’s most up-and-coming neighborhoods. Like neighboring Williamsburg, Bushwick was founded as a Dutch settlement during the 17th century. Over the 19th century, the neighborhood became a haven for German immigrants, leading to a booming brewing industry that brought immense wealth to the area. After World War I, Bushwick’s German enclave was steadily replaced by a significant portion of Italian Americans. In the post-World War II era, as Bushwick’s brewing companies moved out of the city, the neighborhood’s economic base began to erode.

Though discussions on urban renewal occurred with the hope of creating new public housing, these plans never materialized, leaving many of the area’s residential buildings demolished. Bushwick’s economic downtown reached a fever pitch during the July 1977 city blackout, which resulted in widespread arson, looting, and vandalism across low-income neighborhoods. As a result, the neighborhood was left without a commercial retail hub, leading many of Bushwick’s middle-class and white residents to leave during the 1980s and 1990s.

In the 2000s, as real estate prices shot up in Manhattan and nearby Williamsburg, young professionals and artists began moving in droves to Bushwick’s converted lofts and limestone-brick townhouses. Since then, the neighborhood has enjoyed one of the city’s liveliest art scenes. Today, the majority of Bushwick’s population is of Puerto Rican or Dominican descent, and the neighborhood has one of the most populous Hispanic-American communities in Brooklyn. Containing the oldest Dutch fieldstone house in New York City and statues honoring World War I soldiers, Bushwick has many fascinating secrets.

On the border between Bushwick and Ridgewood is the Vander Ende Onderdonk House, the oldest remaining Dutch fieldstone house in New York. The house was constructed around 1709 by Paulus Vander Ende, and the structure’s foundations originate in 1660, when the site was first occupied by Hendrick Barents Smidt. During the 1796 boundary dispute between Bushwick in Kings County and Newtown in Queens County, Van Ende Onderdonk served as a prominent marker. Visitors to the Onderdonk House can view the Arbitration Rock, which marks the contentious border between Brooklyn and Queens.

Since 1975, the Vander Ende Onderdonk House has served as the headquarters for the Greater Ridgewood Historical Society, which helped raise funds to rebuild the home from 1975 until 1981 after it was damaged in a fire. In June 1995, New York City granted the house landmark status. Today, the Vander Ende Onderdonk House serves as a museum specialized in the history of the area, providing visitors with an insight into the legacy of Dutch colonialism in New York City.

In recent years, Bushwick has become known for its growing art scene. Across the neighborhood, there are more than 50 art galleries. These include the Robert Henry Contemporary gallery, which focuses on minimal, abstract, and conceptual work, and Norte Maar, a nonprofit gallery connecting artists, choreographers, composers, and writers to break down barriers that exist between artistic disciplines. Another is the Active Space, an art center with a 1,600-square-foot gallery as well as 37 artist studios. And 56 Bogart houses a number of art galleries and studios — even Jenny Holzer had her studio there.

Every year, the neighborhood also hosts the Bushwick Collective Block Party — founded in 2012 by Joseph Ficalora to beautify industrial streets with vibrant graffiti art. The event brings together legendary NYC graffiti artists and local Bushwick talent at Troutman Street for a day of painting and live music. Afterward, the artist’s work remains on display, covering more or less the entire block between Wyckoff and St. Nicholas Avenue. In addition, the Bushwick Collective works as a year-round nonprofit organization, with new murals being painted every six to 10 weeks.

Following the integration of Bushwick into the city of Brooklyn in 1855, the area began to develop a more localized economy based around factories and industrial complexes. One industry that began to boom in the neighborhood was beer production, due in large part to the influx of German immigrants. At one point, Bushwick had as many as 45 breweries, and a 14-block area near Linden Street and Gates Avenue became known as “Brewers Row” because it had 14 consecutive breweries in operation. As a result, Bushwick was dubbed the “beer capital of the Northeast.”

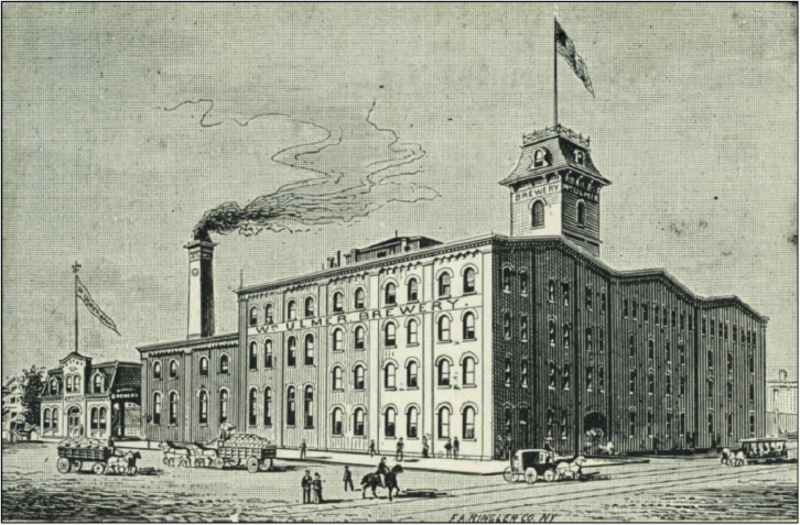

One of the area’s most important breweries at the time was the William Ulmer Brewery Complex, which consisted of an office, a brewhouse, an engine-machine house, and a stable storage house — all built between 1872 and 1890. Though the brewery was highly successful, it ceased operations in 1920 due to Prohibition. Over time, the area’s brewing industry began to decline, and the neighborhood’s last two breweries, Schaefer’s and Rheingold, closed their doors in 1976. Today, many of the abandoned buildings of these long-gone breweries can still be seen. In 2010, the William Ulmer Brewery was given landmark status by the city, becoming the first brewery with this title.

While the heyday of brewing in Bushwick is long gone, the neighborhood is once again one of New York City’s best spots for bar hopping. One of the area’s most unique bars is Boobie Trap, where visitors are greeted by a series of plastic lawn flamingos. Surrounding the area behind the bar is a variety of mannequin busts, with inside walls employing a wide range of kitschy neon colors and psychedelic magazine covers. Below the raised M line between Stockholm and Central Avenue is Bushwick Public House, a cafe and pub with the succinct motto “Coffee, Whiskey, Culture.”

To the east of Maria Hernandez Park is Lot 45, an entertainment space and bar housed in what was once a warehouse. The space is divided into an indoor and outdoor seating section, with a bar for each. In the back of Lot 45 is a nightclub area equipped with dance floors and live music. Besides drinking, guests can also enjoy a variety of games including ping pong and foosball.

Along Bushwick’s southeastern boundary is the Evergreens Cemetery, a nonsectarian graveyard that runs along the border between Brooklyn and Queens. Individuals buried here range from Civil War veterans to vaudevillians. In addition, the cemetery houses the unidentified remains of victims of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, placed beneath a monument of a grieving woman. From the fire, there were eight graves allocated, consisting of one man, six women, and one casket holding an individual whose gender was unidentifiable.

Another notable figure buried is Jonathan Reed, a Brooklyn merchant who bought a mausoleum in Evergreens Cemetery for his wife after her death in 1893 — placing an additional empty coffin next to her for himself. According to reports from the New York Times, Reed decorated the mausoleum “just like a living room in a fine house,” with items such as an oil stove, paintings, photos from Mary’s childhood, and their pet parrot. Every morning, Reed arrived saying, “Good Morning, Mary, I have come to sit with you.” He would then remain at the tomb all day, talking, eating, and reading to pass the time before leaving in the evening. Over the years, word of Reed’s actions spread throughout the community, and others began to join him on his daily vigils — 7,000 people visited him during the first year alone. Seven Buddhist monks from Burma even stopped to sit with him. Reed never missed a single day’s visit and was found dead from a stroke on the floor of the mausoleum in 1905. Immediately he was laid to rest beside his wife, and the tomb has remained closed ever since.

As Bushwick’s brewery industry boomed, the influx of wealth to the area gave rise to several large and ornate mansions mainly located along Bushwick Avenue. One of these was the Lipsius Cook Mansion, built in 1899 for Catherina Lipsius, an owner of Claus Lipsius Brewing Company. Claus Lipsuis’ claim to fame was for its creation of the recipe for Brooklyn Lager. The mansion was designed by architect Theobald Engelhardt in the Romanesque Revival style, with red brick walls complementing the green trimmings and roof spire.

In 1902, the building was sold to Dr. Frederick Cook, a Columbia Medical School graduate who claimed to have been the first American to summit Mount McKinley in Alaska and reach the North Pole. Cook’s claim of having reached the North Pole was refuted in April 1908 by Robert Peary, who is credited as having been the first to reach the site in 1909. Even so, Cook went on to make millions of dollars selling photographs, sending newspaper accounts of his adventures, and lecturing across the country — though he would later be convicted of mail fraud in 1923, leading to a prison sentence of six years. In 1920, the Cook Mansion was bought by an Italian family, who later sold it in 1952 to a Catholic religious order known as the Daughters of Wisdom. It would be used by the organization as a convent until 1960. Today the structure remains abandoned, though it was named an NYC Landmark in 2013.

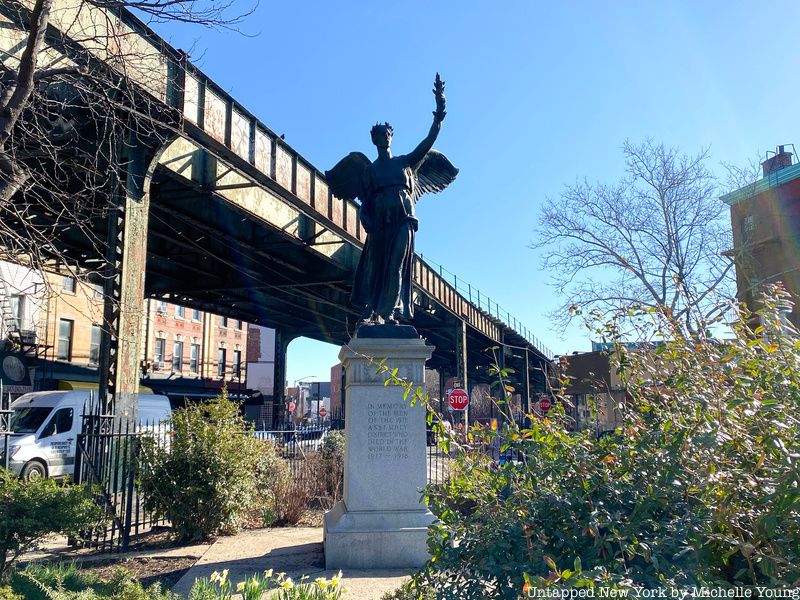

Across from the Cook Mansion at the intersection of Bushwick, Myrtle, and Willoughby Avenues is the Freedom Triangle, which commemorates the Brooklyn men who gave their lives during World War I. Acquired by the city in 1912, the site was given its current name in 1919. Two years later in 1921, Italian immigrant Pietro Montana’s monument Victory with Peace was erected in the park — depicting Nike, the Greek Goddess of victory, leaning forward against an olive branch. Nike’s face was modeled after Claudia Deloney, a Hollywood film actress and friend of Gloria Swanson. The monument is set atop a granite pedestal designed by architect William C. Decay, with an inscription stating, “In Memory of the Men of the 19th Assembly District Who Died in the World War 1917-1918” and the names of the 94 individuals who died from the conflict.

Another war memorial in Bushwick by Montana can be found at Heisser Triangle, located at the intersection of Knickerbocker and Myrtle Avenues and Bleecker Street. The site was named after World War I Sgt. Hessier who lived on Grove Street and perished while serving in the 106th Infantry in France. The statue features Heisser holding a rifle in one hand while the other is clenched in a fist honoring the 156 men from the neighborhood who served during the war.

Amid Bushwick’s bodegas and warehouses lies an urban oasis known as Oko Farms. Previously occupying an abandoned lot, Oko Farms lies at the intersection of Moore and Humboldt Streets. In 2013, Oko Farms became New York City’s first and only publicly accessible aquaponics farm, named after Orisa Oko — the Yoruba deity of agriculture. Through aquaponics, a closed cycle between fish and plants is created, whereby the animal’s excretion is used as plant nutrients. In doing so, the plants filter the toxic waste from the water. Given that 70% of the world’s freshwater is used for industrial agriculture, aquaponics significantly cuts down water usage — giving farmers a more sustainable method to grow their crops.

Oko Farms grows an assortment of flowers and herbs that range from onions and cucumbers to basil and mint. In the past, the farm experimented with using freshwater prawns to help grow beans and peppers. Oko Farms also has a second location at North 3rd and River Street in Williamsburg, where all of the organization’s educational workshops and formal tours take place.

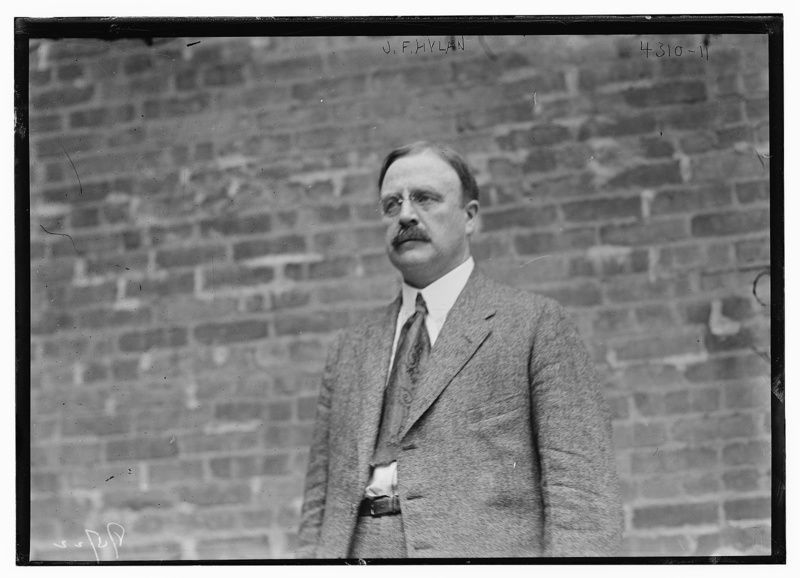

Originally from the rural Catskills, former New York City Mayor John Francis Hylan moved to Bushwick after marrying his childhood sweetheart, Marion O’Hara. They lived at 959 Bushwick Avenue. On the corner of Gates Avenue and Broadway, Hylan would later open up his law office, and although he only made $24 in his first month, he quickly built a strong litigation practice. In 1917, Hyland was put forth as a Brooklyn Democratic candidate for mayor, serving two terms from 1918 to 1925. One of Hylan’s chief focuses was on keeping subway fares from rising. However, by the end of his second term, he was heavily criticized for his handling of the subway by Governor Al Smith. A few years after he left office, in 1937, the New York Times named Hylan as Bushwick’s “best-known resident in recent years.”

Another famous person who has called Bushwick home is actor Anthony Ramos, who grew up in the area with his mother, older brother, and younger sister. The actor is known for starring dual roles of John Laurens and Philip Hamilton in the Broadway musical Hamilton and as Usnavi in the 2021 Lin Manuel Miranda film In The Heights.

While Bushwick today is a largely Hispanic community, it was once one of New York City’s largest Italian American neighborhoods. Bushwick’s Italian community was mainly of Sicilian descent, hailing from the provinces of Palermo, Trapani, and Agrigento. One development that resulted from the neighborhood’s expansive Italian American community was the construction of numerous Catholic churches.

Originally the area’s Sicilian community congregated at Our Lady of Pompeii on Siegel Street, but as industry expanded along Flushing Avenue, they moved into Bushwick to support the growing need for factory operators. After, the center of the Sicilian community came to be at St. Joseph Patron of the Universal Church Roman Catholic Parish, which opened in 1923. The church held five annual feasts complete with processions for saints and Our Lady of Trapani. Today, St. Joseph is a vibrant Latino parish run by the Scalabrini Order of priests, an Italian missionary order that caters to migrants. Masses are held in both English and Spanish.

Another prominent Roman Catholic church that formed in Bushwick was St. Barbara’s, a one-story building, cruciform in plan and set on a granite base with two towers and a dome. The church was built from 1907 to 1910, making it one of the earliest churches in the northeastern United States to incorporate the Spanish Colonial Revival style of architecture — uncommon in the region. Designed by Helmle & Huberty, St. Barbara’s structure incorporates elaborate yellow brick and white terra-cotta decorations including an array of pilasters, entablatures, figurative elements, niches, foliation, quoining, and brackets. Red roof tiles, stained glass windows, and a surrounding historic wrought-iron fence and gate complete the church’s look. Originally St. Barbara’s parish was established in 1893 to serve Bushwick’s German Catholic community, before switching to be for the area’s Italian and Hispanic community by the 1950s and 1960s. Its name was derived from the daughter of Leonhard Eppig, a German immigrant who opened one of Bushwick’s many breweries at 22/32 George Street.

Next, check out 18 Must-Visit Spots in Bushwick, Brooklyn: An Untapped Cities Guide!

Subscribe to our newsletter