A Salvaged Banksy Mural is Now on View in NYC

This unique Banksy mural goes up for auction on May 21st in NYC!

Part of the fascination of New York City lies in what is not usually encountered and most often missing from our cityscape. By this, I mean evidence of the contributions that fabulous women have made to the five boroughs. Over the centuries, women have accounted for roughly half of New York City’s population. But historical documents and histories of the city are invariably lacking in information about New York City’s women. For that information, you need to go underground.

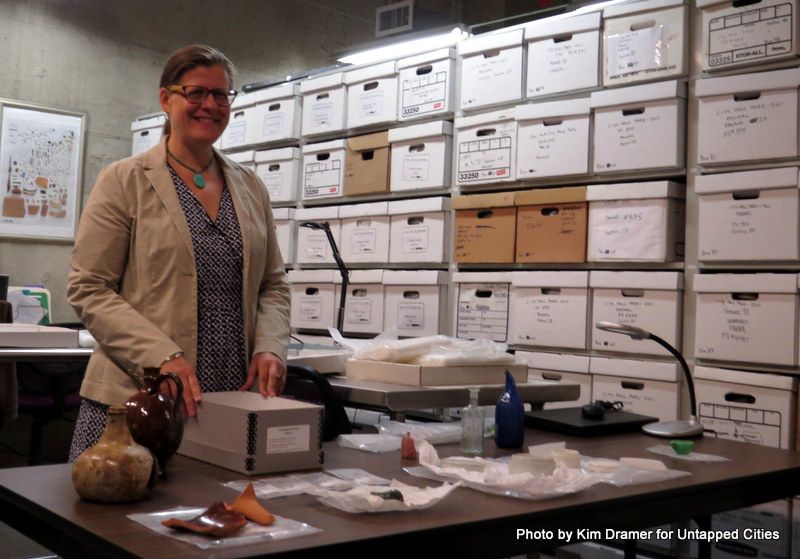

Urban archaeologist, Amanda Sutphin,in the Nan A. Rothschild Research Center of the New York City Archaeological Repository. The underground facility houses over a million objects collected from excavations throughout the five boroughs. Located in the Durst Organization Building on Corporate Row, the facility places artifacts associated with New York women of the past, once again, at the very heart of New York City.

Enter Amanda Sutphin, an urban archaeologist working for the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. Sutphin might be called the city’s quintessential underground woman. She spends her days in the city’s underground, climate-controlled archaeological repository. Here, she works with with artifacts that often spent centuries underground before resurfacing in New York City during archaeological excavations.

When bulldozers dig the foundations of a new building, excavate a new subway tunnel or refurbish a ferry landing, they destroy the archaeological record of the city. Construction projects that take place on city land are required to complete an archaeological survey before the earth–and important evidence of the past is disturbed. In this way, the destruction of the city’s past also turns up artifacts that once belonged to long gone New Yorkers. Once these objects resurface on city land, ownership then transfers to the current generation of New Yorkers.

Artifacts that enter the city’s archaeological repository are used by Sutphin and her colleagues to reconstruct the past for the benefit of contemporary New Yorkers. “These object were found on public land,” explained Ms. Sutphin. “The collection has been catalogued and studied with public money. The public should benefit from these efforts, and we hope to help them do so.”

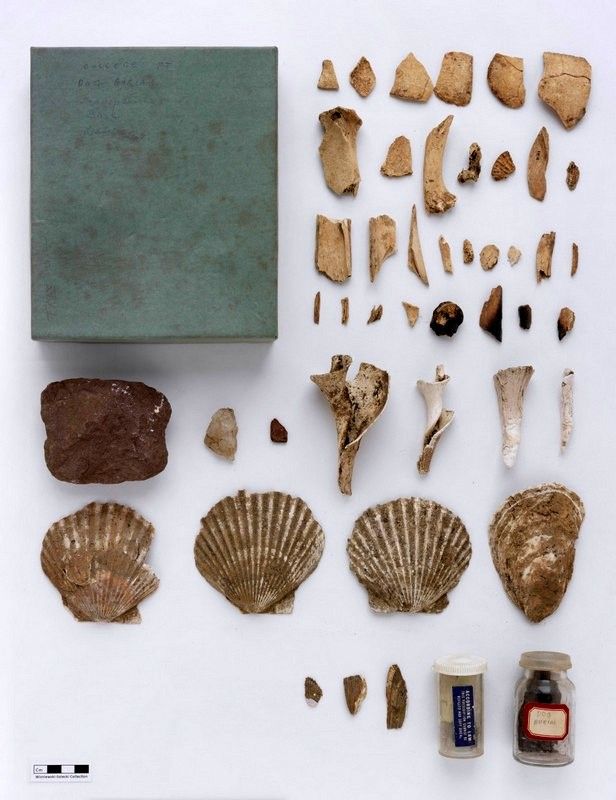

Asked to provide Untapped Cities readers with the earliest example of objects associated with fabulous New York women of the past, Ms. Sutphin points to the city’s prehistory and Native American culture. Archaeological sites from this early period are most associated with exploiting the land for seasonal food sources such as coastal spring fishing camps, fall open air hunting camps, and shellfish collecting stations. Native American women in sites such as the one now at College Point, Queens, worked at collecting and processing food. Artifacts from this site include shells that were discarded after processing and a stone weight used to sink fishing nets.

Whelk, scallop and oyster shells unearthed at the College Point, Queens, prehistoric site. A stone net weight is at left. This site indicates the rich coastal food resources available to the earliest New York women. Photo courtesy New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission.

“The archaeological record of urban New York actually begins in 17th century New Amsterdam,” explains Ms. Sutphin. The Stadt Huys or City Hall, a site in lower Manhattan located at today’s 85 Broad Street, was the site of an archaeological excavation. The Stadt Huys was built by William Kieft, a lesser-known director of the Dutch settlement of New Amsterdam before Peter Stuyvesant and his peg leg arrived in town. The site originally served as a place where officials and guests of the Director were lodged and fed. And drank. A lot.

The archaeological record of The Stadt Huys is rich in bottles and pitchers that held the liquor seemingly necessary for official business of the Dutch city. Locally-made pottery and imported glass bottles were found in abundance at the site.

Found at the Stadt Huys site, a redware pitcher and a glass bottle that were likely hefted by New Amsterdam serving maids, the original New York City waitresses. The locally-made pottery pitcher, modeled on Dutch prototypes, held locally-brewed ale or cider. The glass decanter, an elite object imported from Europe, held imported wine. It was likely used by New Amsterdam’s political elite when attending to official business. Kitchen work and serving were two of the limited options of work for New Amsterdam women.

In 1664, Dutch New Amsterdam became English New York. Artifacts from colonial era New York were discovered during an excavation over an 18th century “ice-box” room on the grounds of what is now the Tweed Courthouse at 52 Chambers Street in lower Manhattan. The 18th century English custom of tea drinking was adopted by colonial New York ladies and was a feature of New York loyalist families (which was most of them.) The evidence of tea drinking squarely places the colony in the middle of the political crisis that loomed when that commodity was taxed by the British. And we all know what happened next….(though New York City remained staunchly loyal to the Crown.)

A green glazed teapot spout from the 18th century might have broken during a tea party hosted by loyalist New York women. The beloved and oft-told (but likely apocryphal) tale of Mrs. Murray and her daughters describes such a party. After the American defeat at the Murray ladies, secret patriots, hosted a tea party for British officers. Their aim was to distract them while American troops escaped pursuing red coats. New York legend says that a maid kept watch at an upstairs window and signaled her mistress once the troops had made their way to safety. The unsuspecting Mr. Murray, a loyalist, provided the tea for the entertainment which took place in today’s section of Manhattan.

Tea was an expensive commodity, usually kept in a box that was kept locked by the lady of the house. And the accoutrements for serving tea were imported elite items including teapots, teaspoons, teacups and saucers.

Jean-Étienne Liotard (Swiss, 1702 – 1789), Still Life: Tea Set, about 1781 – 1783, Oil on canvas mounted on board. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Image from Wikimedia Commons.

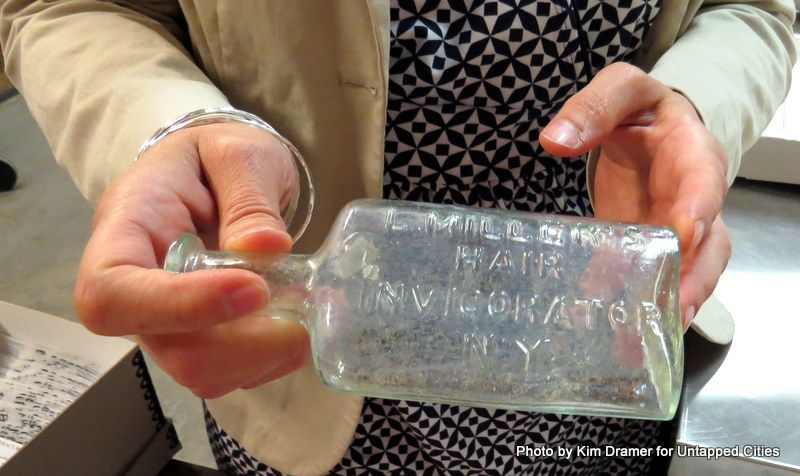

Speaking of New York City women of the 19th century, Ms. Sutphin pointed to three different bottles designed to hold manufactured goods. These artifacts signaled that like today, New York women of the past were responsible for the majority of purchases in the city’s households–thus a driving economic force in the city. A variety of 19th century bottles were excavated from root cellars in Van Cortlandt Park in the Bronx when it morphed from a private home to a public park.

L. Miller’s Hair Invigorator was part of the manufacturing boom in 19th century New York. The product was marketed as a product for mother’s who wished to see their babies grow a lush head of hair (and their balding husbands.)

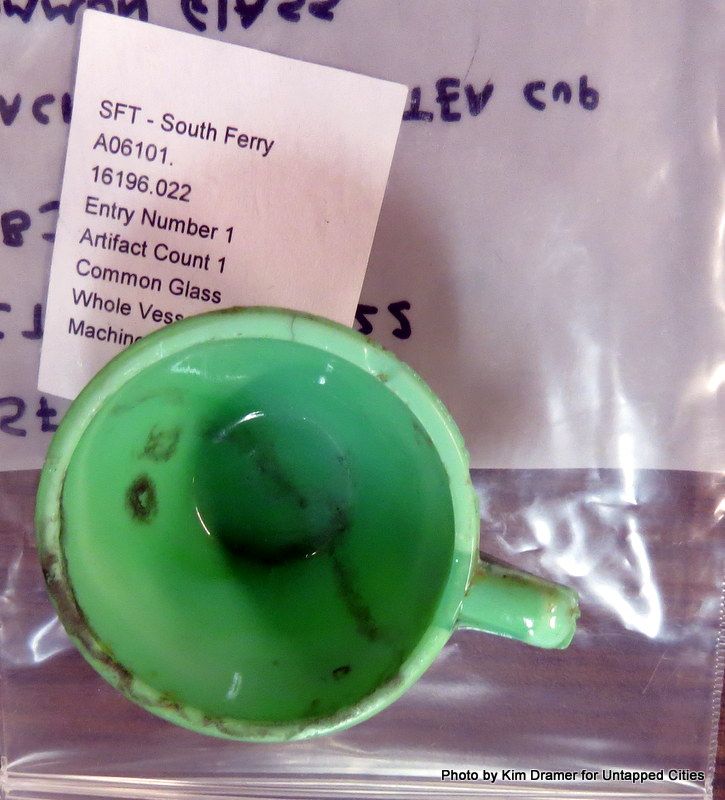

At the southern tip of Manhattan, the renovation of the Battery Park subway tunnel yielded a mid-20th century toy belonging to a New York child. A play teacup made of Depression-era glass was likely lost by a little girl playing in what was then a park.

The child’s replica of her mother’s tea set was manufactured in Akron, Ohio during the Depression. Ms. Sutphin points to modern New York City girls of the 20th century being given a set of expectations that seem to differ little from those of little ladies in colonial era New York.

“Assigning gender to artifacts is often difficult,” warns Ms. Sutphin. “But it is also true that the increasing presence of female archaeologists in New York City has meant that attention is often given to objects that can offer clues to the lives of past New York women.”

And the influence of New York City women who work as archaeologists is overwhelmingly evident in the formation of the city’s archaeological archives. The Nan A. Rothschild Research Center of the New York City Archaeological Repository is named for the Barnard College archaeologist who trained Ms. Sutphin as an undergraduate student. Professor Rothschild persuaded her cousin, Helena Durst, to donate space in the basement of the Durst Organization building, located on Corporate Row on West 47th Street, to house the collection. Three fabulous New York women at work in the city!

The ghosts of New York City women past are among us. They may be underground instead of featured in history books and archives, but they account for half of the actors in our city’s great history. And today’s New York City women archaeologists are working to preserve their past, record their lives and tell the stories of their contributions to the city we know: the good, the bad, the fabulous.

The excavations or digs from which objects enter the collection of the New York City Landmarks and Preservation Commission are situated throughout the 5 boroughs. New York City is the first city in the nation to allow access to its archaeological records through a website. The website lets you browse current and past digs in several ways: using a map, through a list of excavations, or via thematic collections. The themed collections include: Food and Drink in Colonial New York, Historic Toys and Animals Among Us. This final collection includes some of the oldest objects in the archives, and helps us reconstruct the natural environment of New York and its abundant natural resources.

In an effort to bring education about archaeology into New York classrooms, lesson plans for teachers and fun quizzes for kids are also available. If you catch the bug for unearthing Gotham (or other places) and want to study archaeology, the web site offers a list of institutions in the city with formal programs as well as field schools–a way to literally get your hands dirty while learning about digging up the past.

Next, read Eight Highlights from the New York City Archaeological Repository that reflect the lives of New Yorkers of the past and 5 NYC Exhibitions Celebrating Women This Summer.

Subscribe to our newsletter