How to See the Liberty Bell...in Queens

A copy of the famous American bell can be found inside a bank, which itself is modeled after Independence Hall!

Masami Teraoka has a problem with the Vatican. And if you want to see exactly how much of a problem, you should go down to (Art) Amalgamated for Masami Teraoka: Cloisters Inquisition, open until October 24, 2012.

The artist at the opening with a viewer in front of Semana Santa / Cloisters Workout, 2004.

The artist at the opening with a viewer in front of Semana Santa / Cloisters Workout, 2004.

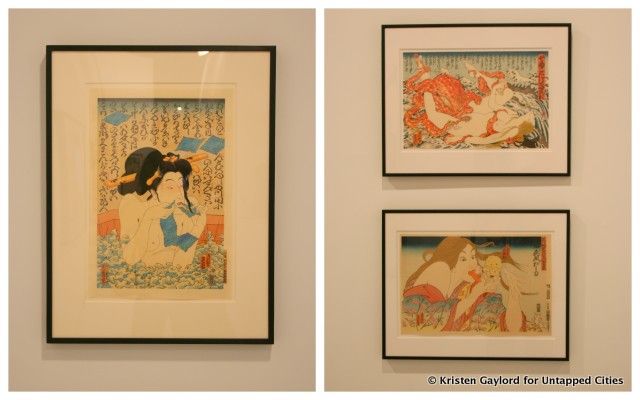

Teraoka was born in Japan, earned a B.F.A. and M.A. at Otis Art Institute in California, and now lives and works in Hawaii. His is an oeuvre steeped in art history. The earliest works on view in this retrospective survey, which features “a tightly curated selection of works highlighting selected points in Teraoka’s artistic career,” are in the Ukiyo-e or “Pictures of the Floating World” tradition. These painstaking and exquisitely executed woodcut prints feature conventional figures in unconventional ways. A geisha uses her teeth to rip open a condom wrapper. A woman feasts wildly upon an ice cream cone. Comprehension of these works involves a gap between the cursory glance, confirming the style and medium, and then the surfacing incongruities: “That Ukiyo-e woman is eating a McDonald’s burger!” Teraoka’s work is most effective in these first moments, as expectations are not merely challenged but shattered. He is not an artist of subtlety, Teraoka.

Left: Masami Teraoka, AIDS Series / Geisha in Bath, 2008.

Left: Masami Teraoka, AIDS Series / Geisha in Bath, 2008.

Right: Masami Teraoka, Sarah and Octopus / Seventh Heaven, 2001

and 31 Flavors Invading Japan / Today’s Special, 1980-82.

A more recent body of work inhabits the style of medieval and Renaissance panel painting, especially of the altar format. It is this work that takes direct aim at the Catholic Church, scrupulously perverting its own religious iconography. And that is precisely the point. Teraoka reacts with outrage to the recent conduct of the institution, including its handling of child molestation and its treatment of females and female sexuality. The anger at injustice conveyed through these paintings fairly blisters. In the tradition of the best political cartoons and caricature, Teraoka skewers the clergy as wanton, gluttonous, privileged profligates.

While political and social art go in and out of fashion, there is no arguing with the fact that the Catholic Church has done extensive damage and continues to fight against many ideals that the artist and others, including myself, treasure. Teraoka has directed the church’s own teachings back against itself in the Dantean fashion of contrapasso, condemning its wickedness within its own narrative. He invokes Christian symbols such as snakes and hellfire, and exposes the clergy’s hypocrisy the same way Jesus once did to the Pharisees.

Masami Teraoka, The Cloisters / Pilgrim, 2010.

Masami Teraoka, The Cloisters / Pilgrim, 2010.

One can’t help but be moved by Teraoka’s work. It is impassioned and righteously furious, and the artist has been committed to social and ethical issues throughout his career including gay rights, American globalization, and censorship. Yet the altarpiece series exposes a kink in his approach. The priests are punished with their own theology, in the style of their own liturgical arts, but the fundamental assumptions are not overturned. At a certain point the circularity started to feel stagnant, and I longed for a breath of fresh air. The Ukiyo-e paintings provided relief through humor, the unexpected, and the clever juxtaposition of coyness and explicitness. The altarpieces, a didactic art form in their own right, are less tempered, and provide little space for reflection except along the very specifically mapped sentiments the artist has provided. I’m sure that Teraoka and I could have a conversation about some of the Catholic Church’s history that would proceed amiably and with a majority of overlap, but these paintings aren’t talking to me, they’re shouting. And I don’t enjoy reading emails written in uppercase.

Get in touch with the author at @kaygegay.

Subscribe to our newsletter