An Original Stone Eagle Comes Home to Penn Station in NYC

A 7,500-pound eagle sculpture from the top of the original 1910 Penn Station building has been returned after years in hiding!

Sing Sing Prison, one of the country’s most notable prisons, has for 200 years led shifts in the national prison system, from the adoption of a system stressing separation from other prisoners to major reform movements. The prison, and specifically its historic Cellblock, has for decades raised conversations surrounding major criminal justice issues such as the architecture of confinement, women in prison, progressive reform, corporal and capital, punishment, congregant and contract labor, mass incarceration and prisons in popular culture.

On June 1, discover the history of Sing Sing Prison at the virtual event Creating the Sing Sing Prison Museum. The event will be led by Sing Sing Prison Museum Executive Director Brent Glass along with his staff. Tickets are free but exclusively for Untapped New York Insiders. Become a member today starting at just $10/month!

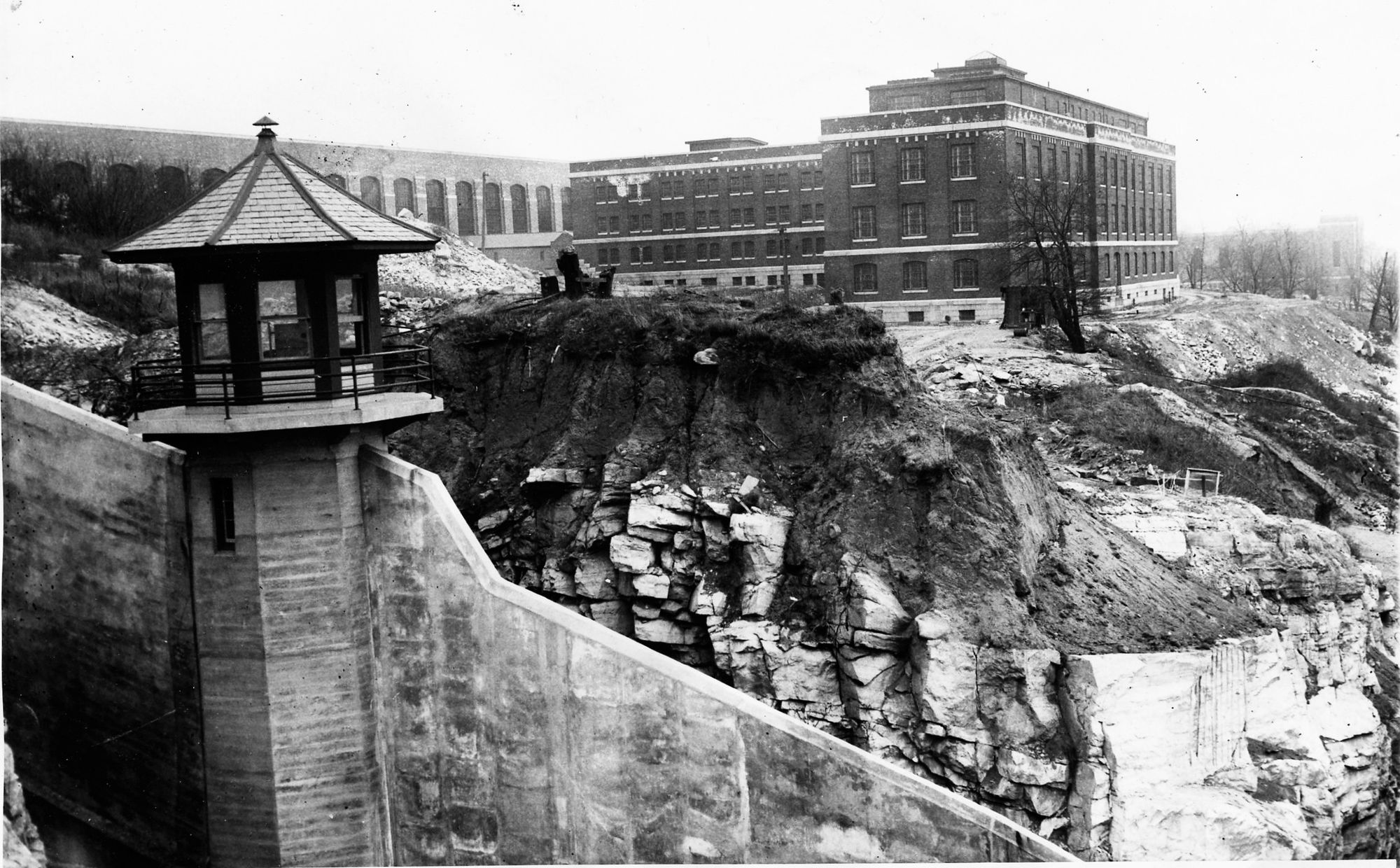

The event will focus on the historic Cellblock built along the Hudson River with rocks quarried by incarcerated men between 1825 to 1828 and on the plans to create the Sing Sing Prison Museum. The event will tell the extraordinary story of 200 years of incarceration at one of America’s most iconic prisons and, as a site of conscience, challenge visitors to imagine a more equitable justice system and take action to build a better society.

Sing Sing Prison, located in Ossining, Westchester, was the fifth prison that New York State authorities constructed. In 1824, a warden at Auburn Prison, located in the Finger Lakes region, was tasked with constructing a more modern prison further downstate. After contemplating a location in Staten Island and The Bronx, the warden decided on the town of Mount Pleasant in Westchester along the Hudson River. The 130-acre site was named after a nearby village, which itself took its name from the Wappinger words “sinck sinck,” or “stone upon stone.”

By May 1825, 100 incarcerated men were transferred to Sing Sing from Auburn Prison, but the prison was not even finished by then. There was no “place to receive them or a wall to enclose them,” and the construction of facilities like temporary barracks and a cook house was severely rushed. However, the main builders of the prison’s Cellblock was not a professional architect nor the state—it was the prisoners themselves. Starting in 1825, Sing Sing’s inmates excavated marble from a nearby quarry to create a 487-foot long, 44-foot wide four-story building. The Cellblock had a capacity for 800 inmates and became the centerpiece for the small town, which also included workshops, a chapel, a hospital, and the nation’s first female prison. It was not until November 1828, after three years of laborious work, that the prisoners would be locked in their cells.

The construction did not stop at the Cellblock, though. Just two years later, the incarcerated mined enough Sing Sing marble to construct two additional buildings, one that served as the hospital and kitchen, and the other a chapel that could contain 900 men. Some of this marble was also used to construct the New York State Capitol Building, the United States Treasury Building, and sections of New York University.

Sing Sing Prison was notorious for its harsh treatment toward the incarcerated. These men were subjected to the “Auburn System,” named for Auburn Prison where the system of punishment was formulated. When mining marble and performing other laborious tasks, the men worked silently in “congregant” labor groups, and this silence continued into the night when prisoners were confined to their solitary cells. Whipping and other violent punishments were common, and the “lockstep” system was used to control and move inmates throughout prison grounds. The Auburn system contrasted with the Pennsylvania system, which put more emphasis on solitary confinement to foster penitence.

There were some attempts to reform this system in the 1840s, though. John Luckey, the Prison Chaplain, created a religious library at the prison that taught moral principles. Eliza Farnham, who was Warden of Mount Pleasant Female Prison, advocated for prison reform by introducing social engagement activities that eliminated the Rule of Silence for the women. The focus now became on framing the incarcerated’s mindsets for the future, not focusing entirely on their past crimes. Despite some disagreements between Luckey and Farnham, the library became a space for prisoners to engage in both religious and secular texts and to focus on education.

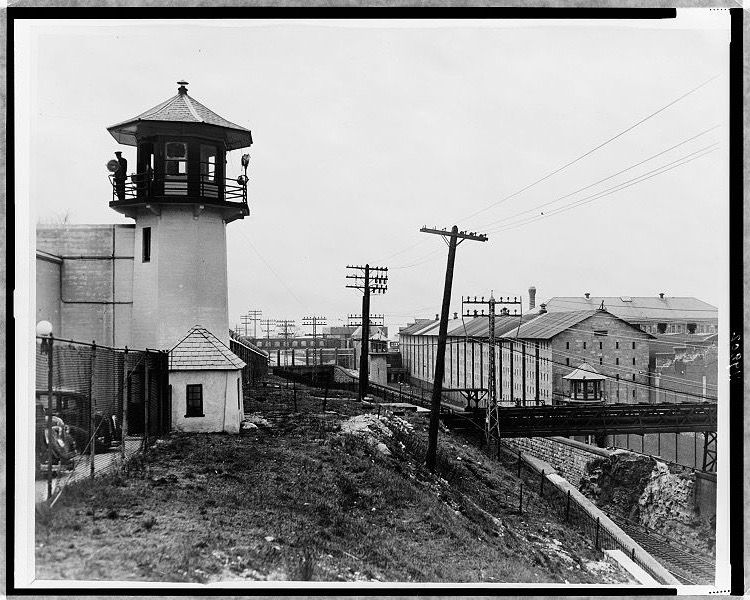

Despite these reforms, the prison remained one of the country’s most strict on the incarcerated. By 1860, the prison added 400 cells, and Sing Sing’s system of congregant labor continued to serve as the dominant philosophy for the nation’s penal system. In 1891, Sing Sing carried out its first execution at its “Death House,” where 614 executions by electrocution took place until 1963. There were numerous death row escapes in the first few decades of the executions, but Sing Sing built a new Death House in 1920 that had stricter security. Using the chair “Old Sparky,” the prison executed such figures as Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, who were accused of committing espionage for the Soviet Union, and Gerhard Puff, who murdered an FBI agent.

By the early 1900s, many of the Auburn System’s components were eradicated or reformed. Warden Thomas Mott Osborne established the Mutual Welfare League, essentially a system of internal self-rule. Osborne cracked down on prisoners who bribed guards and intimidated others, and he was the subject of a conspiracy by those who lost their privileges to be indicted for crimes he did not commit. In the early 1900s, the lockstep system was abolished, and inmates were granted “freedom of the yard” in which they could converse with others and leave their solitary dorms.

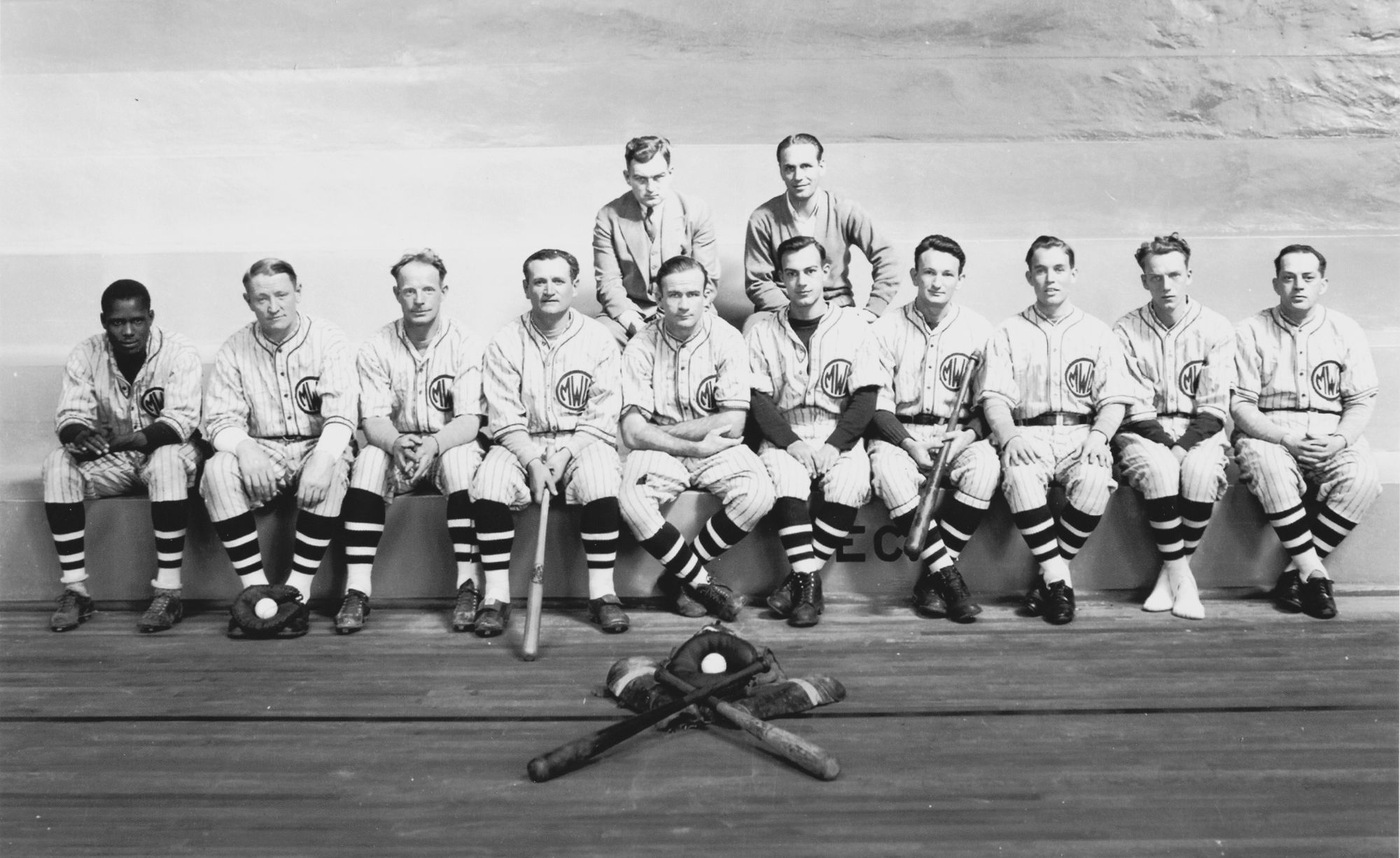

Under warden Lewis Lawes, the “old hellhole” was transformed into a modern prison, although executions still occurred rather regularly. Lawes introduced new educational programs and even organized sports teams; for many years the New York Yankees would play exhibition games against the incarcerated men. The New York Giants owner Tim Mara sponsored the Sing Sing Black Sheep, providing them with equipment and uniforms. For a few years the football program was extremely successful—the starting quarterback Alabama Pitts was signed by the Philadelphia Eagles upon his release, while Jumbo Morano was signed by the Giants. However, a 1936 rule banned the sale of tickets to football games, the revenue from which paid for disbursements to prisoners’ families, and in that year no inmate could play football outside of the prison.

In addition to a library and classrooms, the men also had access to a storehouse, barber shop, and a bath house, as well as a chapel. Lawes had also allowed a former newspaper editor to construct a birdhouse on the prison guards. The prison also became a popular movie backdrop, with Warner Bros. donating funds to construct a prison gymnasium in 1934. Two years after Lawes retired in 1941, the old Cellblock closed down and the metal bars and doors were donated to the war effort.

The 1972 court case Furman v. Georgia ruled that the death penalty was unconstitutional if its application was inconsistent and arbitrary, thus executions stopped at Sing Sing. By then, the prison was completely different from its cruel past a century ago. In 1996, Katherine Vockins founded Rehabilitation Through the Arts, in which prisoners receive a curriculum of theater-related workshops all year. The organization Hudson Link for Higher Education in Prison also provides college courses to inmates both at Sing Sing and at nearby prisons to reduce poverty and recidivism upon release.

The Sing Sing Prison Museum is currently under development with plans to open a Preview Center in 2022 in the former prison Powerhouse. Museum organizers plan to connect the Powerhouse to the historic Cellblock by 2025, the 200th anniversary of the prison’s construction. The museum anticipates having a projected annual attendance of more than 100,000 visitors, displaying the Sing Sing story as it unfolded over time.

Throughout its 200-year history, Sing Sing Prison has led transformations in national prisons from the adoption of the Auburn System to the introduction of sports teams and educational programs. Sing Sing has also become a cultural icon, featuring in films and TV shows like “Alienist,” which depicted an execution. To learn more about the history of Sing Sing Prison, check out the Creating the Sing Sing Prison Museum event at 12 p.m. on June 1st, available to all Untapped New York Insiders!

You can also donate to the Sing Sing Prison Museum here!

Subscribe to our newsletter