Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

No matter how “multicultural” or “mixed” the German capital may often be described as in the media, Berlin’s ethnic reality for the average pedestrian does not inevitably evoke the idea of a big melting pot like New York, London or Paris. But if one listens closely, the colloquial nickname for the street Kantstraße, “Kantonstraße”, is the first indication of a deeper story.

Beyond the Turkish neighbourhoods (Kreuzberg, Neukölln, Moabit, Wedding) that are now part of Berlin’s main attractions, few people know that Berlin has one of Europe’s largest Asian communities. Even more interesting is that this settlement began when the city was still divided, on both sides of the Wall.

The first Chinese visitors in Berlin arrived in the 1820s and the first Chinese settlements began in the 1920s, but it is in Berlin’s post-war history that the actual development of the Asian community began. A large number of Vietnamese workers – and a few Chinese – came to work in East Berlin’s factories (known as contract workers or Vertragsarbeiter), whereas Chinese, Thai and South Vietnamese migrants came to West Berlin. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, some Vietnamese from East Berlin came to the western part of the city in the hopes of improving their situation, and the community steadily grew in the area.

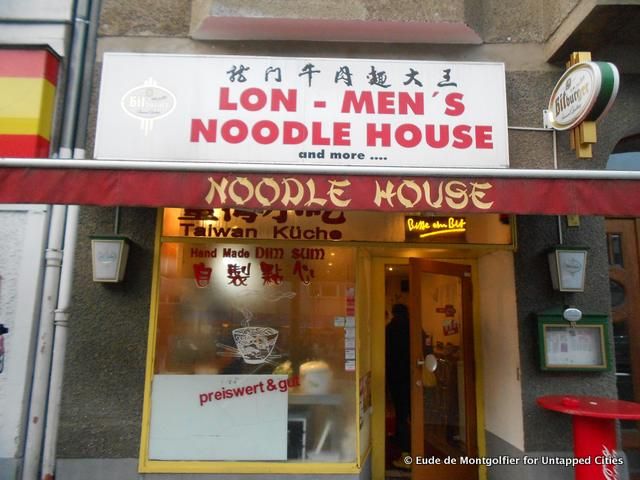

It is precisely in the street often nicknamed “Kantonstraße” because of the numerous Asian shops and restaurants located there, that one can savour the best wonton soup in the city. Lon Men’s Noodle House is is a locally famous noodle bar owned by Mr. and Mrs. Ding, guards of a beef-based Taiwanese soup whose recipe is kept highly secret. The Ding family settled in Berlin in 1968 from Taiwan and took over a restaurant formerly called Tschin.

Mr. Ding was once the Chairman of the Chinese Association of Berlin, an organization aimed at helping immigrants from Taiwan and China, mostly caterers, with administrative procedures, often because their German was too poor. Mr. Ding even lobbied to the Berliner Senate the idea of creating an official Chinatown in the Kantstraße with the project of renaming the street. The idea was refused, allegedly for social order reasons, at a time where there were tensions between the Chinese and Turkish communities. But if the philosopher Kant, for whom the street was originally named for, knew his street was renamed for food reasons, he would probably turn in his grave!

Subscribe to our newsletter