Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

Can an African city that is intent on forging ahead economically hold onto its architectural heritage while encouraging new development? This question is particularly urgent in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania’s largest and wealthiest city—and gateway to important tourist destinations such as Zanzibar, the Serengeti, and Ngorogoro Crater. The Tanzanian government is convinced that Dar’s economic future lies with concentrated, high-rise commercial development downtown, which means wiping out the low-rise, mixed-retail-and-residential buildings that have given Dar its charm and character since the early 20th century. It’s in some ways a universal battle, as Dar-based architect Annika Seifert has pointed out about Singapore and Kuala Lumpur, and as Untapped has noted about Istanbul.

Yet Tanzania’s destructive strategy is unusually easy for the government as landowner to apply. Most of the vulnerable colonial buildings, which are operated by long-term lease-holders, can simply be demolished with almost no notice and without American-style public hearings. The government need not invoke costly eminent domain procedures—as, say, American cities must—to implement urban renewal. It can wait until a lease expires, bulldoze the buildings, and redevelop the property into tower blocks.

Until recently revoked, a 1964 law that recognized some structures as being worthy for historical, architectural, or cultural reasons gave limited protection to a few monuments and buildings. Suspending that order to allow demolition was justified, said Minister of Water and Irrigation Jumanne Maghembe to The Citizen newspaper, because “we are transforming from a poor country into a middle-income nation, and this cannot be realised by keeping old buildings intact.”

But the shock of overnight demolitions—rubble where lovely buildings stood the day before—has been galvanizing residents into questioning government policy. Journalist Elsie Eyakuze, for example, writes that the “eternal struggle between brutish, mechanical modernity and the organic present and past has become a battle to the death.” The above photo by Tanzania Daily News photographer Mohamed Mambo of Samora Avenue is especially shocking because Samora is a remnant of fine early 20th-century city planning–once a wide tree-lined boulevard meant to move people and goods efficiently but also beautifully.

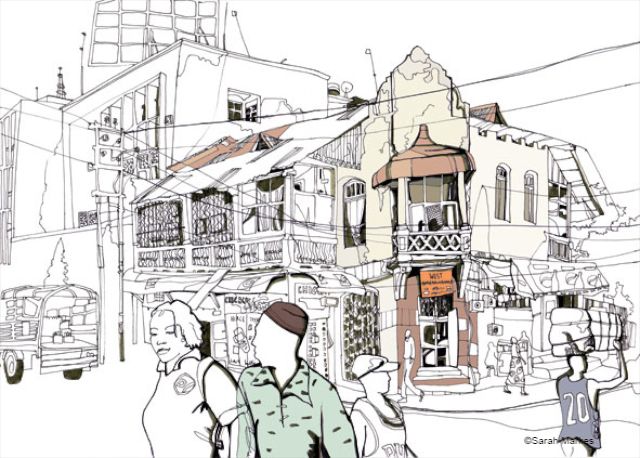

Architect Seifert especially mourns the loss of Dar’s traditional Swahili houses, Indian merchant structures, and early post-independence buildings and monuments. Dar resident and artist Sarah Markes, who has been sketching such buildings for ten years, published a book, Street Level, in 2011 documenting their presence–and all too often, their loss. Buildings that were then “threatened with demolition” have subsequently been destroyed.

Here are three demolished buildings that once stood on Samora Avenue. The first, the Light Corner Shop, was built by a Goan pioneer between 1905 and 1914, says Marks, at a time when the Goan Christians were the only non-Europeans allowed by the then-German government to build along and south of Samora Avenue. This mandated racial and ethnic segregation produced many damaging consequences, of course, one of which was to encourage local hostility or indifference to the architecture. Yet, as Markes notes, the series of connected early retail buildings along Samora “form a rare and important historic streetscape,” with retail on the ground and residential above.

The Blaschke House (1907) was built for a German settler for combined commercial and residential use. The extensive use of balconies, writes Markes, helps ventilation and keeps the building cool–classic vernacular and sustainable coastal architecture.

Demolished over a weekend in mid-August, the Quality Shop (c. 1928-35) was probably one of the first to be built, says Markes, in a period of concentrated development as a European shopping street by the British administration between the mid-1920s and mid-1940s. She writes, “Flamboyant trees, which had shaded the street in earlier times, were removed to make room for growing traffic.”

Certainly it is distressing that in its commercial downtown Dar has—and is destroying—precisely the attractive and sustainable urbanism now so admired by urbanists worldwide. Downtown Dar has traditionally mixed commerce and residences with retail and sometimes manufacturing uses on the ground floor and comfortable living quarters above. People lived close to where they worked, allowing density to flourish. The new model is to build single-purpose, highly secure commercial towers that more often than not bar street life. Workers pour into downtown from far-away residences in the morning, and drive out again at night. With almost no public transportation to support the density, congestion will soon reach untenable levels.

Still, there’s hope because many historic buildings remain standing, despite the many demolitions. The Architects Association of Tanzania has established a Centre for Architectural Heritage in Dar es Salaam (DARCH), which intends to research, document, and help preserve threatened buildings.

City lovers around the world can also make a contribution: travel to Dar, stay in its hotels, patronize its restaurants, talk to its residents, and walk downtown.

Street Level: A collection of drawings and creative writing inspired by Dar-es-salaam can be bought on Amazon. Markes’s art can be found at Dar Sketches.

Julia Vitullo-Martin is a Senior Fellow at the Regional Plan Association and director of its Center for Urban Innovation. Get in touch with her @JuliaManhattan.

Subscribe to our newsletter