Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

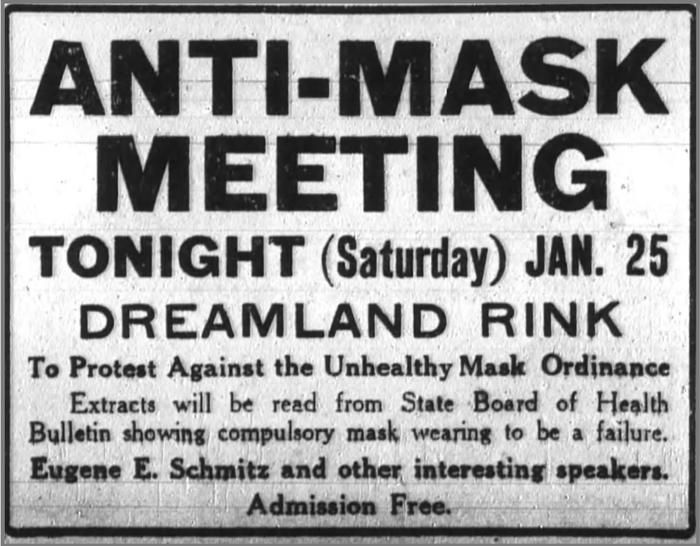

A clipping from the San Francisco Chronicle on January 25, 1919. The San Francisco Chronicle.

On the morning of January 25th, 1919, an advertisement ran in The San Fransisco Chronicle promoting an “anti-mask meeting” at the Dreamland Roller Rink later that night. The admission free meeting had the self-proclaimed intent of protesting “against the unhealthy mask ordinance” that required citizens of San Francisco to wear masks in an effort to combat the influenza pandemic (also known as the Spanish Flu). It was but one example of the larger cultural dispute that swept throughout the United States as the health crisis continued into its second year. With this in mind, the story of the anti-mask league is insightful as the U.S (New York included) navigates the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, highlighting how public opinion about a city’s policies can change over the course of a health crisis.

Before discussing the actions of the anti-mask league, it is critical to remember just how widespread and deadly the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918 was. The flu infected 500 million people around the world, 27% of the world’s population, and killed anywhere from 17 million to 50 million people. In New York City, 33,000 residents died — with 65% of the deaths occurring in the second wave. In the first year of the pandemic, the average life expectancy in the United States dropped by a staggering 12 years.

The pandemic, however, constantly lived in the shadow of World War I, which was unraveling in tandem with the health crisis. Even though the pandemic ended up being deadlier than the war, the conflict helped shape the policies of governments and the opinions of citizens. The first recorded infection in the U.S. was even discovered among the army’s ranks, when a soldier stationed at Fort Riley, Kansas on March 4, 1918 reported symptoms. Although the United States and the other nations at war initially suppressed news of the flu (neutral Spain freely reported it, hence the title “Spanish flu”), as governments began to institute policies to prevent the disease’s spread there was a sense that following these new health precautions was a patriotic way to support the war effort.

A traffic cop wearing mask in New York City in October 1918. Photo from National Archives.

Throughout cities in the U.S., responses to the growing pandemic were put in place. New York City was particularly vulnerable due to its many ports bringing soldiers to Europe but still developed a surprisingly effective response, including a timetable of when certain businesses could open and the establishment of temporary health centers throughout the city. In mid-October of 1918, New York City also recommended that citizens wear masks to protect themselves, but the ordinance only made the mask required for barbers. However, historic photographs demonstrate many New Yorkers wearing masks, including police officers.

Similar mask ordinances were created throughout the country, including Washington D.C., Phoenix, and Oklahoma City. Yet like New York, these ordinances were mostly limited to certain professions (mainly police, healthcare, and personal care). In fact, even some Americans came to welcome the masks as a fashionable accessory, as evidenced by a Seattle Daily Times articles that references women “wearing fine mesh with chiffon border to ward off malady“. Yet despite the praise, masks at the time were made of gauze, a porous and highly ineffective material. Additionally, Americans were prone to wearing masks incorrectly, with the common practice of poking holes into them in order to smoke.

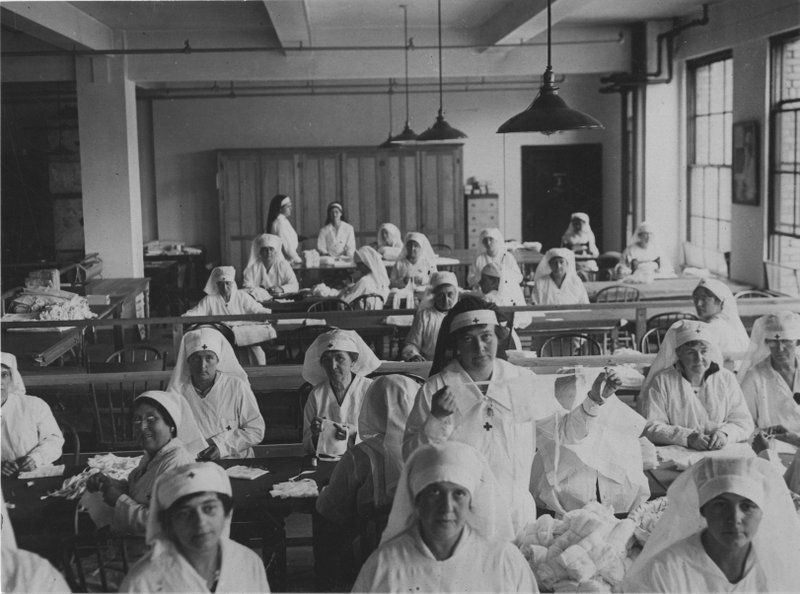

Making guaze masks at Red Cross Headquarters in Washington D.C., October 1918. Photo from National Archives.

Yet the wearing of masks faced the most pushback in San Francisco, where enforcement was the most strict and criticism about the masks’ effectiveness and their negative impact on civil liberties was the most intense. San Francisco’s precautions against the disease were the most intense in the country and quite possibly the world (there is very little record of mask wearing in Europe during the pandemic), with businesses, restaurants, and theaters all closed and the city’s Board of Health issuing an advisory against large gatherings (although some gatherings were still held outside, including church service and court trials). Additionally, the city made mask-wearing mandatory for all citizens on October 25, 1918. At first, the city experienced widespread compliance to the order, aided by Red Cross volunteers who distributed masks to citizens. However, as enforcement of the mask policy became more severe, public perception began to shift. On October 27, 110 people were arrested by police officers either refusing to wear masks in public or wearing them improperly. Although there had already been reports of citizens only wearing masks when police officers were around, this incident was the first major step in the city’s escalating mask conflict.

A church service being held outside Grace Cathedral in San Francisco during the Spanish flu pandemic 1918. Photo from California State Library.

Tension over the masks escalated, including another round of 175 arrests on November 2, 1918. An even more violent incident occurred on October 29, when a mask-less citizen and a health inspector came to blows in the streets of the city, resulting in gunfire that injured two bystanders. San Franciscans against the mask ordinance were upset over the apparent hypocrisy of office holders, especially after the city’s mayor and public health officer were both fined for attending a crowded boxing match without masks. There was still hope that the situation would become less tense as the pandemic cooled down and the city reopened. On November 16, theaters, entertainment venues, and sporting arenas began reopening, and on November 21 the mask ordinance was also dropped. However, the hope was short lived as December saw a great increase of influenza cases in the city. After poor attempts at asking citizens to wear masks voluntarily. San Francisco reinstituted its mask ordinance on January 17 of the New Year.

A policeman wearing a mask speaks to a mask-less man in San Francisco in 1918. Photo from California State Library.

The new mask ordinance, and in a larger sense the second wave of the disease, sent San Francisco spiraling towards a tipping point. Popular discontent against masks had been brewing since October of the year prior, with the ineffectiveness of masks, the hypocrisy of state officials, and the limitation of civil liberties all cited as valid criticisms against them. The anti-mask league was born from this frustration, and drew in a great number of San Franciscans all against the new mask ordinance. The league boasted impressive membership, including the influential suffragist Emma Harrington and a former mayor of San Fransisco in Eugene Schmitz. The anti-mask league, often referred to as “mask slackers” or “sanitary spartacans“, advertised and held a public event on January 25, drawing 4,500 people to the Dreamland Roller Rink in an effort to end the mask law. After the meeting, the league submitted a petition to the city calling for the ordinance’s repeal, stating that “we earnestly pray that the people be granted speedy relief from the burdensome provisions of this measure”.

A policeman wearing a mask leads two men away from the San Francisco Ferry Building in 1918. Photo from California State Library.

However, despite the league’s popular support, the ordinance was not repealed. Mayor James Rolph firmly stated that he would “repeal this ordinance when the doctors, the Board of Health and common sense permit.” He also tied the mask issue back to the war once again, saying, “do you think I am going to stultify myself here against the wish of 99 1/2 percent of the doctors; against the officials of the army and navy?” The anti-mask league moved to hold another meeting on February 1, yet ironically, the city repealed the mask ordinance of its own accord on that very same day. As a result, the meeting ended in turmoil, with multiple changes to the organization’s leadership before they ultimately disbanded the league by the meeting’s end.

A mask ordinance was not reinstituted in San Francisco during the Spanish flu pandemic. Despite the intensity that surrounded the mask question, use of masks as a public health measure did not continue after the pandemic, even while handkerchiefs began to be fashionable among wealthier Americans. However, during the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, masks once again represent a cultural divide within American society. While it is imprudent to draw parallels directly between the medical realities of the Spanish flu and coronavirus, the lived experiences of individuals within the pandemics bring to light curious similarities. For example, while the initial response to mask usage may have been positive in both instances, anti-mask sentiment began to accrue over time as the health crisis dragged on. As concerns over a second wave of coronavirus grow (with increased cases as states reopen), the story of the anti-mask league in San Francisco demonstrates how the true danger of a public health crisis lies not only in the initial response but also in enduing practices.

During protests this past June, many marching individuals wore masks.

Additionally, both health crises were also set to the backdrop of other key cultural moments. In the case of the Spanish Flu, World War I permeated the national consciousness, with mask usage finding initial support with the imbued meaning of patriotism. Support of the masks (and all discussion about the disease for that matter) also decreased after the war, which points towards the correlation between conversations about the two. In the case of the coronavirus pandemic, the Black Lives Matter movement has become closely tied to the experience of the pandemic. As protests sweep the nation, conversations surround questions over how the pandemic disproportionately affects low-income communities and how and if protests can operate during a public health crisis. So while direct comparisons between two pandemics separated by a century might be faulty practice, a conversation between the two does highlight the ways in which health crises are both affected by and have an impact on the cultural, political, and social moments of their time. Such is the case with the anti-mask league, a story that offers insight not just into the Spanish flu, but also the people who experienced it.

A Note on Sources: Chapter 20 of Samuel K. Kohn, Jr.’s book Epidemics: Hate and Compassion from the Plague of Athens to AIDS and the University of Michigan’s online Influenza Encyclopedia were consulted as secondary sources for this article. All facts not specifically linked to other sources came from these two works.

Next, read about How NYC survived the Spanish Flu Epidemic.

Subscribe to our newsletter